Afghanistan: Fleeing the Taliban into Pakistan and leaving dreams behind

BBC

BBCWith the Taliban taking control of Afghanistan, thousands have fled their homes in fear. While much of the attention has focused on the crowds thronging Kabul airport, thousands of others have fled to neighbouring Pakistan over the Chaman border. Shumaila Jaffery speaks to some of them.

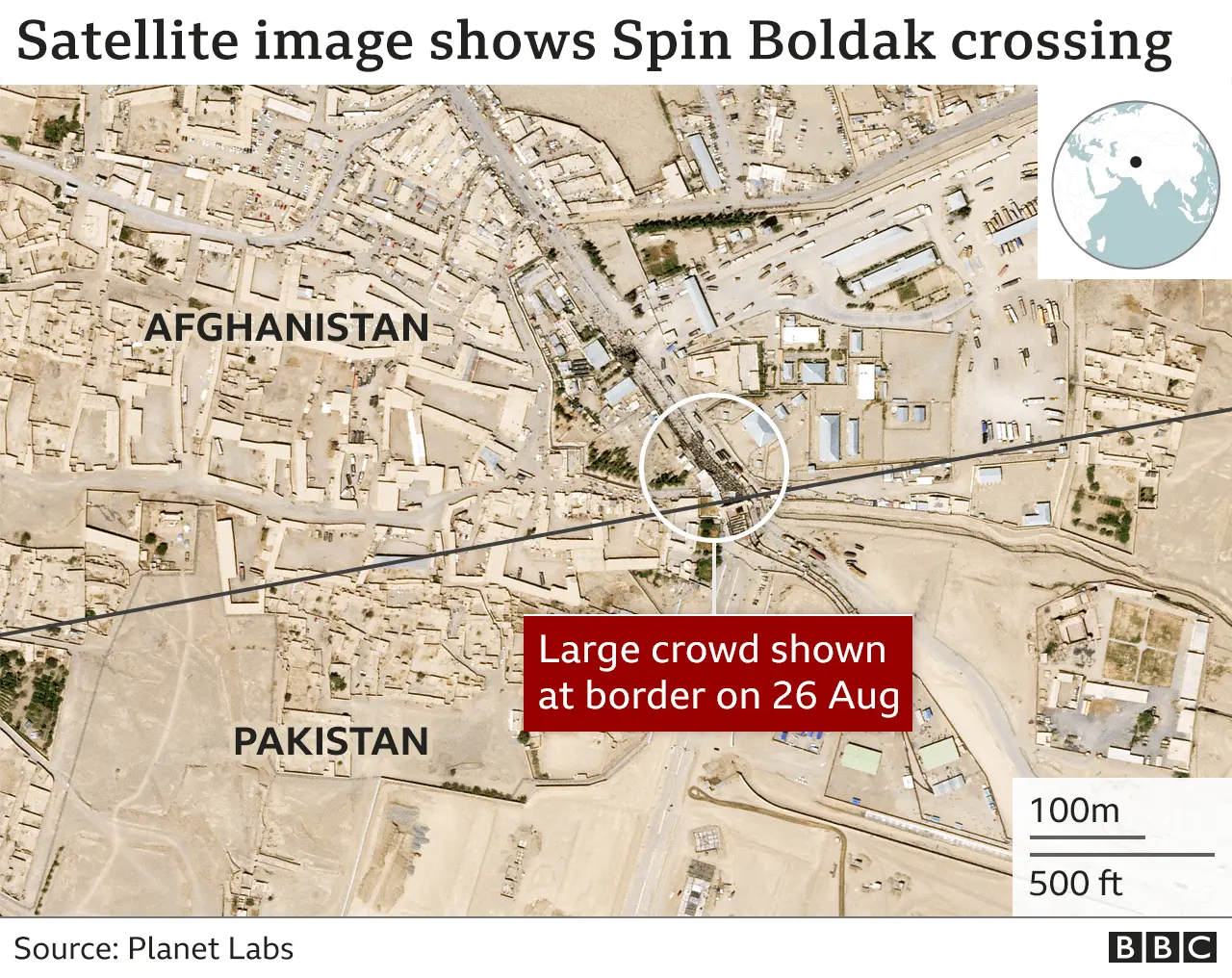

The Chaman Spin Boldak border is one of the busiest crossings between Pakistan and Afghanistan with thousands of traders and travellers passing through this dusty town every day.

But these days, the traffic from the Afghan side is particularly high as thousands flee possible persecution by the Taliban.

From dawn till dusk they pour in - hundreds of men with luggage on their shoulders, burqa-clad women walking briskly behind their men, children clinging to their mothers, exhausted in the scorching heat, and even patients pushed on wheelbarrows.

'They will raid our houses'

Zirqoon Bibi*, a 57-year-old woman belonging to the minority Hazara community, has only just arrived in Pakistan when I meet her.

The Hazara group has been persecuted by the Taliban in the past, with a recent brutal attack on some men of the community reigniting fears of what Taliban rule would look like for them.

"My heart is burning (with pain)" she repeatedly sobs when I ask how she is. "I ask myself what will become of my son, my only son".

Her son, who works for a British company, has been trying to leave the country without success.

She says she already lost her daughter-in-law to a bomb blast by the Taliban targeting the Hazara community a few years ago.

"I felt so lost (after her death) that I couldn't sleep for a long time. The Taliban are terrible people, I am scared of them".

Before arriving in Pakistan, Zirqoon Bibi was housed in a small makeshift camp on the border with around 24 other Hazara women and children from different parts of Afghanistan.

She left her home in the capital Kabul along with her two daughters and granddaughter.

As she speaks, her granddaughter sits on her lap, completely oblivious to the fact that she has no home now.

"I don't care about my house or our belongings, I am only worried for my son and his daughter," Zirqoon Bibi says while gently massaging the child's shoulders.

"Where can I go? what can I do? I have put this girl's mother in the grave with my own hands. It takes a lot of effort and love to raise children, I can't lose another one".

Zarmeeney Begum*, a 60-year-old Afghan who is a Shia Muslim, has also just arrived with a group of other women. Shia Muslims in Afghanistan have been targeted by the Taliban in the past.

She says when her community received news of the Taliban takeover, they felt they had no option but to leave Afghanistan.

"We fear the Taliban will resume their acts of terrorism again. They will conduct raids on our houses. They are already looking for government officials. We feel that bombings may start any day," she says.

'Disrupted futures'

Many of the new arrivals are young Afghan men and women who feel that their futures have now become uncertain.

Among them is Muhammad Ahmer* who was studying and working as an English language instructor in Kabul.

He is still in disbelief over how quickly Kabul fell.

"It was so unbelievable. To be honest, we didn't know they would take all of Kabul in just one night. But I was only scared about my school and my education," he said.

He said he currently doesn't know what to do next, but is certain that his future doesn't belong to Afghanistan under the current rule.

"I want to make my own choices in life, I want freedom, so I am not going back."

Jamal Khan*, also a student in Kabul, has similar sentiments.

"Everybody wants to live in their homes, but we were forced to leave Afghanistan. We are not feeling good about migrating to Pakistan or other countries, all people are worried, but they don't have any hope," he says.

Others say there is no hope of survival under the Taliban.

Obaidullah*, a labourer from Kandahar says he decided to flee to Pakistan because "businesses are destroyed, there is no government and the economy is in complete shambles".

"The situation in Kandahar is normal, but there is no work, I have come here so I can find some work, I will probably drive a rickshaw," he said.

Meanwhile, the Taliban has been trying to portray a more restrained image since its takeover. This is reflected in the stance of one foot soldier who stops to talk to us at the border.

He insists the situation is completely peaceful now and says the "trauma of the Afghan people will end as soon as foreign occupation forces leave the country".

"It's only a trust issue, people will soon know that we mean what we have promised," he adds.

But even as people pour in, they say these words mean little.

"The Taliban may act differently this time, but people who have suffered from their hands in the past are not ready to trust them yet," says Mr Ahmer.

They flee even though they know their futures are uncertain.

Pakistan is already hosting millions of Afghans and says it cannot deal with another influx.

Many believe it's only a matter of time before Islamabad completely halts their entry.

The Pakistan government has already said that unlike the 1980s, when millions of Afghans came over following the Soviet invasion, this time refugee camps would be set up on the borders and Afghans would not be allowed into the heartland.

So far however, people are free to enter the country through the Chaman Spin Boldak border. But they understand the window is small, so they are willing to take any risk to get out.

Where they can go after that remains to be seen.

*Names have been changed to protect identities