The Rohingya refugees trapped on a remote island miles from land

Lu Yang/BBC

Lu Yang/BBCWhen Dilara set off from the Bangladeshi coast, she dreamed of a new life in Malaysia.

But she and hundreds of others who had crammed into the boat ended up being rescued, having spent days floating at sea, after being turned away at the border.

Yet they were not returned to the mainland and the families they had left behind.

Instead, their rescuers left the group on an island created out of silt in the middle of the Bay of Bengal, with no hope of escape.

"I don't know how long I will be here. I have no way out," the unmarried young woman, who fears leaving her room after dark, told the BBC.

"I will grow old and die here alone."

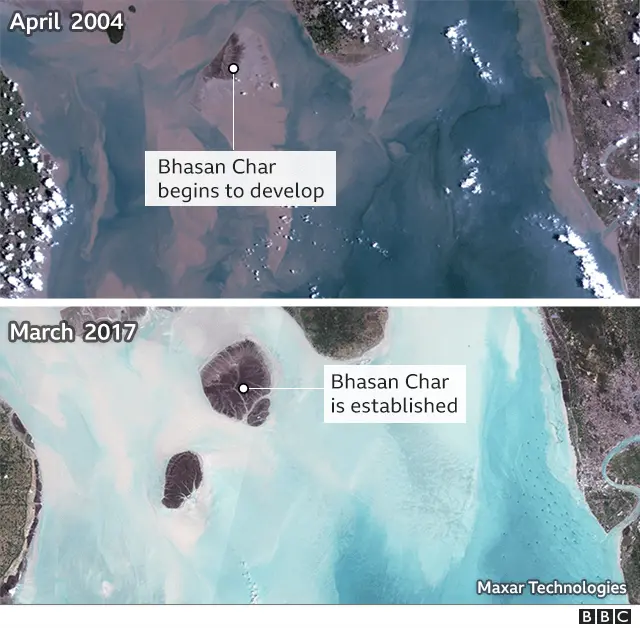

Dilara was among the first of a planned 100,000 Rohingya refugees to arrive on Bhasan Char, a piece of land measuring 40sq km (15 sq mi) in size which had only previously been used as a brief stop-off point for fishermen.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBangladeshi authorities have heralded it as part of the solution to the overcrowded refugee camps in Cox's Bazar, home to almost a million Rohingya refugees who arrived in recent years. Most of them fled a military offensive by Myanmar's army in 2017, which the United Nations later described as a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing". Some had fled earlier violence.

But the refugee camps where the Rohingya have now made their homes have become, authorities say, hotbeds of crime. The new $350m (£246m) development on Bhasan Char - an island which emerged 15 years ago from the sea - is touted as a fresh start.

But refugees the BBC spoke to by phone on this small island of Himalayan silt say differently. They describe a place where there is no work, few facilities and little hope of a better future.

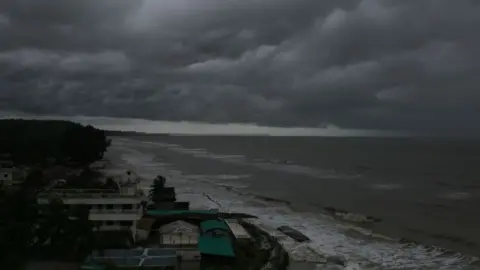

Those who try to flee, they say, are caught and beaten, while refugees are turning on each other as frustrations rise. Worse, at just 2m (6ft ) above sea level, they fear one big storm could wash them away.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite the BBC being granted a tour of the island last year, it is hard to say what is happening there. No journalists, aid agencies or human rights groups have been given free access to Bhasan Char, which is 60km (37.5 miles) from the mainland.

These are the voices of a few residents, and their names have been changed to protect their identities.

'Such a desolate place'

"I wondered how we would survive here," Halima said, recalling the December night she arrived, heavily pregnant, with her family.

"It was such a desolate place. Apart from us, nobody lived here."

Their isolation became all too clear the next day when she went into labour, with no possibility of finding a doctor or nurse.

"I had experienced childbirth before, but this time it was the worst. I can't tell you how painful it was."

Her husband, Enayet, rushed to get a Rohingya woman living in the same block, who had some experience and training as a midwife.

"God helped me," says Halima. She had a girl and named her Fathima.

Enayet had signed them up for a new life on the island without telling his family.

"They [Bangladesh officials] promised us many things like a plot of land for each family, cows, buffaloes and loans to start a business," he told the BBC.

The reality has been very different, although Halima says she is happy with the running water, bunk beds, gas stove and shared toilet in her accommodation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe biggest problem is they can't afford anything more than very basic food.

Families in Bhasan Char are provided with staples like rice, lentils and cooking oil. But the refugees need to buy other items like vegetables, fish and meat. There is no market, but some Bangladeshis run shops on the island. Travel to the mainland is impossible: no ferry service exists, and the navy - which runs the facility - only transports the refugees one way.

"We are poor people," Halima says, "We don't have any income to buy food and other stuff."

It was food which sparked the island's first protest back in February. Video seen by the BBC shows Rohingya women and men running with sticks and shouting.

Officials downplayed the event.

"It was not a protest," says Shah Rezwan Hayat, the head of the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC), which manages Bangladesh's refugee camps.

But refugees say desperation is growing and some are risking their lives to leave Bhasan Char.

"Many people tried to flee from the island. As far as I know, at least 30 people have left the island," said one resident, Salam.

"I have heard about an incident, where about five people were caught while trying to flee from the island. They were taken to the police camp and beaten up by police."

It is not the only allegation of violence by authorities towards the refugees. Human Rights Watch has said children were punished for moving out of their designated areas.

"On 12 April, a Bangladesh sailor allegedly beat four children with a PVC pipe for leaving their quarters to play with refugee children in another area," the report from last month said.

Enayet says he had heard about these two incidents from others in the camp.

"I have heard children were beaten up for going to a different cluster. And several people, who were detained while trying to escape, were tortured."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSalam says the frustration among refugees is giving way to anger.

"There are daily fights in the camps between refugees. If you keep some chickens in a coop, and don't feed them, then what happens? They start fighting each other."

The navy, which is in charge of constructing the shelters in the camp, denies allegations of torture and abuse.

The United Nations say it has been unable to independently verify the allegations, which it is investigating. However, it wants the camp to be transferred from the navy to civilians and managed in an "inclusive and consultative manner".

Meanwhile, the government has promised schemes to provide income will soon be rolled out to help the 18,400 refugees now living in the camp, and the many others who will soon join them.

It is currently considering applications from more than 40 local NGOs.

'A big prison'

Back in her accommodation, Halima is tired of waiting for things to get better. She has given up on returning to Myanmar, where Rohingyas have faced decades of discrimination.

But neither does she want to live on Bhasan Char.

"I have never lived in a place like this, surrounded by the sea. We are trapped here. We can't go anywhere."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDilara - the young refugee woman who tried to reach Malaysia - says she is scared and alone. But one thing she doesn't want to do is reach out to her parents, still in a refugee camp in Cox's Bazar.

Dilara doesn't want them to suffer as she has.

In fact, all the refugees who spoke to the BBC said they would go back to the mainland, if given the chance. Enayet sums it up.

"If you want to live in a big prison with your family," he says, "this island is the place."