Myanmar coup: Detained Aung San Suu Kyi faces charges

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPolice in Myanmar, also known as Burma, have filed several charges against the elected civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi following Monday's military coup.

She has been remanded in custody until 15 February, police documents show.

The charges include breaching import and export laws, and possession of unlawful communication devices.

Her whereabouts are still unclear, but it has been reported that she is being held at her residence in the capital, Nay Pyi Taw.

Deposed President Win Myint has also been charged, the documents show - in his case with violating rules banning gatherings during the Covid pandemic. He has also been remanded in custody for two weeks.

Neither the president nor Ms Suu Kyi have been heard from since the military seized power in the early hours of 1 February.

The coup, led by armed forces chief Min Aung Hlaing, has seen the installation of an 11-member junta which is ruling under a year-long state of emergency.

The military sought to justify its action by alleging fraud in last November's elections, which Ms Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) won decisively.

What are the details of the charges?

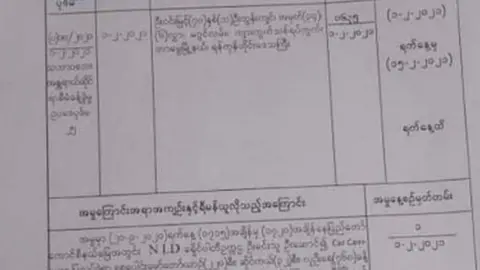

The accusations are contained in a police document - called a First Initial Report - submitted to a court.

It alleges that Ms Suu Kyi illegally imported and used communications equipment - walkie-talkies - found at her home in Nay Pyi Taw.

Myanmar police

Myanmar policeShe was remanded in custody "to question witnesses, request evidence and seek legal counsel after questioning the defendant", the document says.

Mr Win Myint is accused, under the National Disaster Management Law, of meeting supporters in a 220-vehicle motorcade during the election campaign in breach of Covid restrictions.

Given the gravity of the military's power grab, claiming that Myanmar's national unity was at stake, and the storm of international condemnation that's followed, these charges seem comically trivial.

But they may be enough to secure the military's objective of barring Aung San Suu Kyi from political office, as members of parliament cannot have criminal convictions.

For 32 years the generals have tried, and failed, to neutralise the threat posed by Aung San Suu Kyi's enduring popularity. She has won every election she's been allowed to contest by a wide margin.

The only election she did not win was one held by the military government 10 years ago - back then she was also barred from contesting by a bizarre criminal conviction which was imposed on her after an American man managed to swim across a lake in Yangon to her home, where she was being held under house arrest.

What opposition is there to the coup?

MPA

MPAActivists in Myanmar are calling for civil disobedience.

Many hospital medics are either stopping work or continuing but wearing symbols of defiance in simmering anger over the suppression of Myanmar's short-lived democracy.

Protesting medical staff say they are pushing for the release of Ms Suu Kyi.

They are wearing red, or black, ribbons and pictured giving the three-fingered salute familiar from the Hunger Games movies and used by demonstrators last year in Thailand.

Online, many changed their social media profile pictures to one of just the colour red.

"Now young people in Myanmar... have digital power, we have digital devices and we have digital space so this is the only platform for us" Yangon Youth Network founder Thinzar Shunlei told AFP.

"So we've been using this since day one, since the first few hours that we are opposing the military junta."

A Facebook group has been set up to co-ordinate the disobedience campaign.

But there have been few signs of major protest. On Tuesday night, drivers honked their horns in the main city, Yangon (also known as Rangoon), and residents banged cooking pots.

Myanmar has been mainly calm following the coup, with troops on patrol and a night-time curfew in force.

There have also been demonstrations in support of the military - one attracted 3,000 people, AP news agency reports.

Hundreds of MPs were also detained by the military but were told on Tuesday they could leave their guest houses in the capital.

Among them is Zin Mar Aung, an NLD MP who spent 11 years in jail on political charges under military dictatorship.

She told BBC Burmese she had now been given 24 hours to leave the MPs' compound.

"Currently the situation is very very tough and challenging," she said. "Under the military coup it's very dangerous if we speak out about what will be our next steps... only thing that I can say is that the MPs of parliament will stand with our people and vote."

Aung San Suu Kyi - the basics

Getty Images

Getty Images- Rose to international prominence in the 1990s as she campaigned to restore democracy in Myanmar during decades of military dictatorship

- Spent nearly 15 years in detention between 1989 and 2010 after organising rallies calling for peaceful democratic reform and free elections

- Awarded Nobel Peace Prize while under house arrest in 1991

- Led her NLD party to victory in Myanmar's first openly contested election in 25 years in 2015

- Reputation tarnished by failure to condemn military campaign which saw more than half a million civilians from Muslim Rohingya minority seek refuge in Bangladesh

How are other countries reacting to the takeover?

The Group of Seven major economic powers said it was "deeply concerned" about the coup and called for the return of democracy.

"We call upon the military to immediately end the state of emergency, restore power to the democratically-elected government, to release all those unjustly detained and to respect human rights," the statement released in London said. The G7 comprises Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US.

But efforts at the United Nations Security Council to reach a common position came to nought as China failed to agree. China is one of five permanent members with a right of veto in the council - the UN body responsible for maintaining peace.

China has been warning since the coup that sanctions or international pressure would only make things worse in Myanmar.

Beijing has long played a role of protecting the country from international scrutiny. It sees the country as economically important and is one of Myanmar's closest allies.

Alongside Russia, it has repeatedly protected Myanmar from criticism at the UN over the military crackdown on the Muslim minority Rohingya population.