Why a new generation of Thais are protesting against the government

Getty Images

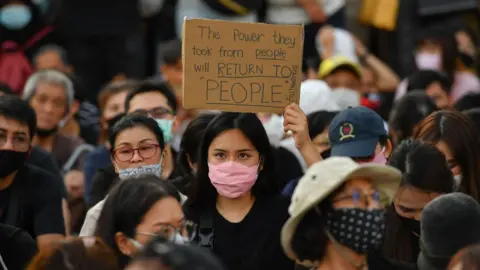

Getty ImagesThey're young, they're angry, and they're calling for change.

Thailand's youth were among thousands on the streets of Bangkok last week in one of the biggest anti-government protests the capital has seen in years, despite a coronavirus ban on large gatherings.

They say they will continue protesting if their three main demands are not met - for parliament to be dissolved, for the constitution to be rewritten, and for authorities to stop harassing critics.

Many have found creative ways to protest - including the use of a Japanese anime character and a "Hunger Games" salute.

Disillusioned youth

Thailand has a long history of political unrest and protest, but a new wave began in February this year, after a popular opposition political party was ordered to dissolve.

March 2019 saw the first elections since the military seized power in 2014. For many young people and first-time voters, it was seen as a chance for change after years of military rule.

But the military had taken steps to entrench its political role, and the election saw Prayuth Chan-ocha - the military leader who led the coup - re-installed as prime minister.

The pro-democracy Future Forward Party (FFP), with its charismatic leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, garnered the third-largest share of seats and was particularly popular with young, first-time voters.

But in February, a court ruled FFP had received a loan from Thanathorn which was deemed a donation - thus making it illegal - and the party was forced to disband.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThousands joined street protests, but these were halted by Covid-19 restrictions.

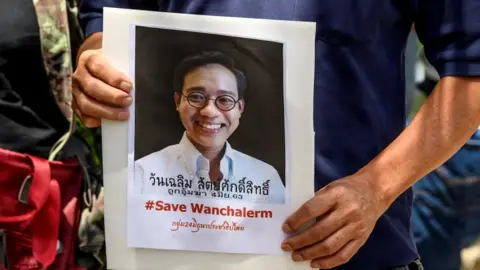

Things heated up again in June when a prominent pro-democracy activist went missing.

Wanchalearm Satsaksit, who had been living in Cambodia in exile since 2014, was reportedly grabbed off the street and bundled off into a vehicle.

Protesters accused the Thai state of orchestrating his kidnapping, which the police and government have denied.

Hamsters and milk tea

Punchada Sirivunnabood, a professor of politics at Mahidol University, says this combination of events has driven the new wave of protest.

"The students feel like what the government has done is not really democratic. They want a fair government," she told the BBC.

Disillusioned by years of military rule, protesters are now demanding amendments to the constitution, a new election, the prime minister's resignation and an end to the harassment of rights activists.

The protests are technically banned under Thailand's coronavirus state of emergency - and breaking this ban carries a sentence of up to two years in jail.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe movement is largely leaderless, but driven by a group known as the Free Youth.

This group, says Dr Aim Sinpeng at the University of Sydney, is "loosely composed of a number of university student associations and affiliated groups… [there's] no leader on purpose".

She says they've learned from the Hong Kong protests of recent years, "where these groups represent free individuals that come together rather than being anchored down by particular organisations or political parties".

Pro-democracy - and anti-China - protesters in Thailand, Hong Kong and Taiwan have even dubbed themselves the "Milk Tea Alliance" - after the classic drink loved in all three places.

And the Thais have found creative - and sometimes whimsical - methods of protest.

A Japanese hamster character, for example, has been turned into a rebel symbol.

Protesters have taken the Hamtaro theme song and changed its lyrics, using it as an anti-government anthem.

A line in the song which says "the most delicious food is sunflower seeds" has been changed to "the most delicious food is taxpayers' money".

Protesters have also been seen giving a three-fingered salute, a gesture taken from the Hunger Games film franchise where it's a rousing symbol of defiance against an authoritarian state.

"Thai youths have always used more subversive pop culture forms of discontent," Dr Sinpeng says.

"That's because of years of living in repressive environments that do not always allow for freedom of expression. [They're] having to always find creative ways to get around all kinds of censorship."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs well as in Bangkok, small "flashmob" type protests which are easy to organise and can quickly disperse are being organised in smaller cities, driven by social media.

"Twitter has really gained ground in the past few years," says Dr Sinpeng. "The trending hashtags are not only important for mobilising public participation, but it is also a branding exercise for a movement that is still forming with evolving and dynamic identities."

A generational divide

According to Prof Punchada, part of the issue is about the older generation not understanding what the students want.

"Most of them support this government, but the young people have opposite ideas."

Unlike previous conflicts between the Red and Yellow shirts - supporters of opposing political factions in Thailand - "this conflict is between the older and younger generation," she says.

"There [have been] off remarks from senior officials that are patronising and demonstrate a deeply-held belief among some older sections of the population that 'kids should not defy their elders'," says Dr Sinpeng.

"[The youth] want to know the elders running the country hear them and take their concerns seriously. They want respect."

Back on the streets, a real fight continues to brew - but is this protest wave likely to have much impact?

"The protests are not going to shake up the government too much now as they are not at the scale that they could yet," says Dr Sinpeng.

"[They] are notable, but will require more momentum."