The children of Korean War prisoners who never came home

BBC

BBCWhen the Korean War ended in 1953, about 50,000 South Korean prisoners of war were kept in the North. Many were forced into labouring jobs against their will. Some were killed. Now their children are fighting for recognition, writes BBC Korea's Subin Kim.

No matter how hard she tries, Lee cannot recall what happened after three shots were fired by the executioners who killed her father and brother. It was three decades ago, when Lee was in her thirties.

She does remember what happened just before. Security officers had dragged her to a stadium in a remote village in North Korea called Aoji. She was forced to sit under a wooden bridge, waiting for something - she knew not what - to happen.

A crowd swelled and a truck pulled up, and two people were escorted off the truck. It was her father and brother.

"They tied them to stakes, calling them traitors of the nation, spies and reactionaries," Lee told the BBC in an interview recently. That's the moment her memory falters. "I think I was screaming," she said. "My jaw was dislocated. A neighbour took me home to fix my jaw."

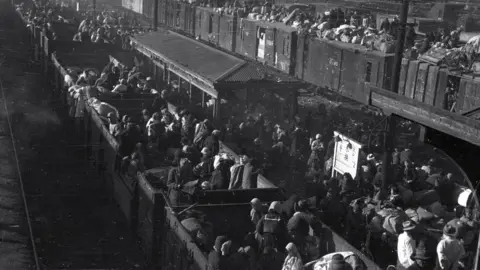

ICRC / HANDOUT

ICRC / HANDOUTThe forgotten prisoners

Lee's father was one of about 50,000 former prisoners of war who were kept in the North at the end of the Korean war. The former prisoners were regrouped against their will into North Korean army units, and forced to work on reconstruction projects or in mining for the rest of their lives.

When the armistice was signed, on 27 July 1953, the South Korean soldiers had assumed there would soon be a prisoner exchange and they would be sent home. But a month before the armistice, South Korean President Syngman Rhee unilaterally freed more than 25,000 North Korean prisoners, in order to sabotage the ceasefire. He wanted UN forces to help him reunite the country under South Korea. Many believe the move made the repatriation of South Korean prisoners more difficult.

The North only sent back a small fraction of the prisoners it had taken.

Soon South Korea largely forgot the men. In years since, three South Korean presidents have met North Korean leaders, but the prisoners of war were never on the agenda.

AFP

AFPIn the North, the Lee family were viewed as bad stock. Lee's father was born in the South and had fought alongside United Nations forces in the Korean War, against the North - a black mark against him. The family's low social status relegated them to backbreaking jobs and dim prospects. Both Lee's father and brother worked at coal mines, where fatal accidents were a regular occurrence.

Lee's father harboured a dream of going home one day, when the country was reunited again. After work, he would tell his children stories of his youth. At times, he would prod his children to escape to the South. "There will be a medal for me, and you will be treated as children of a hero," he would say.

But Lee's brother, while drinking with friends one day, let slip the things their father would say. One of the friends reported it to the authorities. In a matter of months, Lee's father and brother were dead.

In 2004, Lee managed to defect to South Korea. It was then that she realised her father's error - his country did not see him as a hero. Little had been done to help the old prisoners of war get home.

The soldiers kept back in North Korea suffered. They were viewed as enemies of the state, men who had fought in the "puppet army", and assigned to the lowest rank of North Korean social caste of "songbun".

Such status was hereditary, so their children were not allowed to receive higher education or the freedom to choose their occupation.

Choi was a star student, but her dream of going to a university was impossible because of her father's status. She once yelled at her father, "You reactionary scum! Why don't you go back to your country?"

Her father didn't yell back, but said to her dejectedly that their country was too weak to repatriate them. Eight years ago, Choi abandoned her family and fled to the South.

"My father wanted to come here," she said. "I wanted to come to the place the person I loved the most in my whole life wanted to come but never could. That's why I abandoned my son, my daughter and my husband."

Choi's father is now dead. And in South Korea, on paper, she has no father, because official documents say he died in action during the war.

Bringing my father’s bones home

Son Myeong-hwa still clearly remembers her father's last words on his deathbed nearly 40 years ago. "If you get to go to the South, you've got to carry my bones with you and bury me where I was born."

Son's father was a South Korean soldier who was from Gimhae, some 18km (11 miles) away from Busan. In the North he was forced to work in coal mines and a logging factory for decades and only allowed to go home 10 days before he died of cancer.

He told Son: "It is so bitter to die here without ever seeing my parents again. Wouldn't it be good to be buried there?"

Son defected in 2005. But it took her eight years to get her father's remains out of North Korea. She asked her siblings to dig up her father's remains and bring them to a broker in China. Three suitcases were needed. Two of Son's friends came along, but it was Son who carried her father's skull.

Son Myeong-hwa

Son Myeong-hwa Son protested for more than a year for the recognition of her father's status as an unrepatriated soldier, and eventually she was able to bury his remains at the national cemetery in 2015.

"I thought that I finally fulfilled my duty as a daughter," she said. "But it breaks my heart when I think of him having had his last breath there."

Son discovered later that the family paid a terrible price for the burial. Her siblings in the North were sent to political prisons.

Son now heads the Korean War POW Family Association, a group that fights for better treatment of roughly 110 families of South Korean soldiers who never came home.

Through a DNA test, Son was able to prove that she was her father's daughter - which was essential for her to file for his unpaid wages from South Korea. Even if they manage to escape to the South, the children of prisoners of war are not officially recognised, and many of the unrepatriated prisoners were considered dead, or discharged during the war, or simply missing.

Yonhap

YonhapOnly a handful of prisoners of war who managed to escape to the South ever received unpaid wages, and those who died in captivity in the North were not eligible for any compensation.

In January, Son and her lawyers filed a constitutional court case, arguing that the families of the prisoners who died in the North had been treated unfairly and that the government had done nothing to repatriate the prisoners, making it responsible for the prisoners who never came back.

"We were so sad to be born the children of the prisoners, and it was even more painful to be ignored even after coming to South Korea," Son said.

"If we can't recover our fathers' honour, the horrendous lives of the prisoners of the war and their children will be all forgotten."

Some names were changed to protect contributors' safety. Illustrations by Davies Surya.