Christchurch mosque shootings: The lives lost and the world they revealed

NurPhoto/Getty Images

NurPhoto/Getty ImagesThe life stories of the Christchurch mosque victims are a striking reflection of a world in turmoil - one marked by war, poverty and economic inequality.

In New Zealand, many thought they had found a safe, remote corner of Earth on which to build new lives. That changed last Friday at 13:40 when a gunman casually opened fire.

"I was so happy that I had a beautiful country to raise my kids in," says Mazharuddin Syed Ahmed, a survivor of those attacks. "This really hurts me."

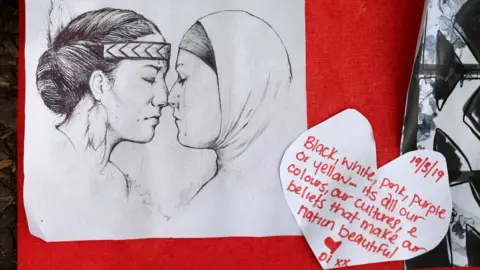

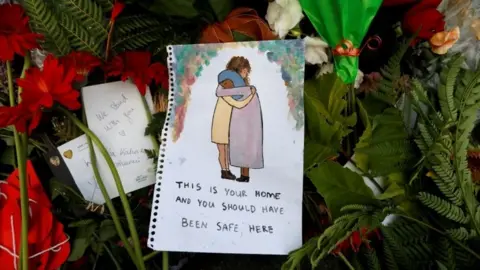

In the week since 50 lives were abruptly taken, Christchurch has come together with powerful messages of unity. For many here, this has opened their eyes to a diverse and complex community they previously gave little attention.

But it is also a reminder of how easy it is for hatred to proliferate and then explode - and a closer look at the stories of those who attended the mosques last Friday is also a stark portrait of just how fragile their worlds had always been.

'They run away from death'

Khaled Mustafa, 44, and his son Hamza, 16, were refugees. They had escaped the war in Syria along with three other family members.

The family had spent time in Jordan at first, before they were accepted under New Zealand's refugee resettlement programme.

Handout

HandoutThey naturally assumed New Zealand was a safe place and had been there for less than a year when they were killed at the Al Noor mosque on Deans Avenue, the site of the first of the two attacks.

Abo Ali, a Syrian man who moved to New Zealand in 1990, says he met the family just once but they were "so happy to have a better life".

"They run away from the death, and they die here," Mr Ali tells the BBC.

Hamza's younger brother, Zaid, was also at the mosque. He survived, but was injured. He attended the funeral of his father and brother on Wednesday in a wheelchair, after surgery.

"I shouldn't be standing in front of you. I should be lying beside you," he was reportedly heard muttering at their graveside.

BBC

BBCMr Ali says the news hit the local Syrian and Muslim communities hard.

"But after, when we see the New Zealand people's support, and when we see the Christian people in New Zealand too, their support - believe me, we forget about our problem."

His dream to make hers come true

In many ways, 24-year-old Ansi Alibava's path to New Zealand was an unlikely one.

She was born in Kerala, India, and not into a wealthy family. After her father died in Saudi Arabia, where he had been working, she began looking after the family, aged just 18.

Her husband Abdul Nazer says that when they first met, he was struck by how she was "supporting everything".

Family handout

Family handoutThe couple had migrated from India a year ago to pursue her dream of studying and travelling overseas. It had been his dream to make hers a reality, he said.

It was only when his father agreed to pledge his house for a loan that the pair were able to get to New Zealand. It was the first time either had even been outside of Kerala. After securing jobs in Christchurch they had been supporting both families at home.

Mr Nazer can only manage a few words as he describes the bliss they shared in New Zealand.

She loved her studies, he says, sitting in a room at Christchurch's Lincoln University where she was working towards a masters degree in agricultural engineering. She had recently begun an internship.

He had just been telling his cousin Fahad Ismail Ponnath, who was there to support him, how the campus brought back so many "lovely memories" - rooms they had been in together, places they had walked.

But last Friday the couple went to the Al Noor mosque as usual, going their own ways into the male and female areas.

BBC

BBCWhen the gunfire erupted, Mr Nazer fled the building and leapt over a fence into a nearby property.

The owner of that house initially didn't let him in "thinking that he was one of the terrorists maybe," Mr Ponnath says.

But he soon left the safety of that house to look for his wife, and he found her lying motionless on a street. As he moved towards her, calling out, other survivors intervened to tell him she had died. Soon the police were there, moving everyone, including her husband, away.

In limited English, Mr Nazer, 34, says of his wife: "She's a really lovely person. Very kindly."

"She loved all people," he says. "Cousins, friends. She kept a big space in her mind [for] family members. Especially my father and my mother, my brothers."

Mr Nazer doesn't know for sure whether he'll remain in New Zealand, but it is likely, as he is now committed to supporting Ms Alibava's family - they have no breadwinners left.

'My husband - what a lovely man'

On Wednesday, flowers and tributes were starting to pile up outside Mohammed Imran Khan's takeaway shop, Indian Grill.

Mr Khan, also known among friends as Imran Bhai, died in the Linwood mosque.

BBC

BBCOriginally from India, he was an immensely popular figure in Christchurch.

"It's just been an absolutely overwhelming [amount] of texts and messages or communications from people I don't even know - just saying what a lovely man he was," his wife Tracey says.

"I knew that people loved him, not so much to this extent, I think. He was a very known man throughout the community for just his heart and giving of time and everything else."

She is focused on looking after their teenage son, as well as her husband's relatives.

"It's very difficult being over the other side of the world and hearing this, and not having information," she says, with relatives arriving from around the world.

'This country is safe'

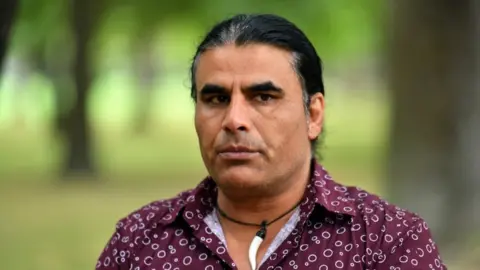

Having spent much of his life in his native India and then Saudi Arabia, Mazharuddin Syed Ahmed says he "couldn't comprehend" how safe and inclusive New Zealand was when he arrived.

He used to tell his friends overseas: "You're scared to death to go to airports. Here, we love the airport. It's like fun - we enjoy it, it's like a pleasure trip for us. Because this country's safe."

Mr Syed Ahmed says the Linwood mosque was home to a small and close community.

"We really love to go on Friday and we were praying," he says, emphasising the final word.

He cannot believe what happened to him and his friends in the country he regards as the greatest on Earth.

Mr Syed Ahmed says he froze when he heard three gunshots interrupting Friday prayers.

EPA

EPAPeople continued briefly to pray but his ears "were completely focused - there is something happening". Then, he says, one man started yelling: "Take cover, take cover - move, move, move."

Despite hearing shots, he ran straight towards the main door - he doesn't know why - and took cover in a storage space next to door when the gunman came in.

He believes he was saved by another worshipper, Abdul Aziz, who took on the attacker by hurling a credit card machine at him.

"But that time, I saw my friend right in my line of sight," Mr Syed Ahmed says. "[A] big splash of blood was on the wall - I could see that he had died there."

'A kind of outrageous character'

The dozens of victims largely began their lives outside New Zealand, in South Asia and the Middle East, in Somalia or Fiji, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Family handout

Family handoutLinda Armstrong, 64, was a New Zealander but her life had been far from conventional, her nephew Kyron Gosse says.

At one point, as "a bit of a hippy", she had lived on Waiheke Island near her home city of Auckland "in this little hut in the middle of the bush with only a long drop [toilet] and no shower", he says. At other times, she had settled in lofts and granny flats, ridden a motorbike, and travelled extensively - once living in Berlin.

Always curious, she found Islam in 2011 while volunteering in a refugee centre in Auckland and talking to people there.

"She'd want to know - why? What do you believe?" Mr Gosse says. "And as she found out more and more about Islam, she told me: 'These are really beautiful people and this religion really resonates with me'."

He describes his aunt as "a kind of outrageous character" who had always been rebellious and a bit stubborn.

She brought her stubbornness to the mosque. Following one conversation with a younger relative, she took issue with the plastic waste being generated there - so she went out and bought everyone reusable plates.

Reuters

ReutersShe rarely had much money but was endlessly generous. Despite living on welfare payments, she began donating NZ$50 (£25; $34) per month to a refugee family from Syria.

"She never met them, she just heard about it and thought: what can I do?" Mr Gosse says.

Ms Armstrong "wasn't in the best of health", so she was seated at the back of the mosque when the violence came. That didn't stop her moving quickly to protect others.

"She put herself in front of one of her friends, took the bullet, and then died in her arms with the imam saying a prayer over her," Mr Gosse tells the BBC.

"We're all pretty proud that that was the sort of person she was."

'Our brother is missing'

Across Christchurch this week, locals have been comparing the collective trauma to an earthquake that struck the city in 2011, killing 185 people.

It is, many say, a similar pain although they are fully aware that this particular pain has been inflicted by a person, and on a specific community.

After an earthquake, a city can rebuild - a physical healing of its wounds.

BBC

BBCOne victim, Zakaria Bhuiya was part of that process. He had moved to Christchurch from Bangladesh to work on the post-quake rebuild, according to the Indian Social and Cultural Club.

Mr Bhuiya, a welder, had taken annual leave on Friday to celebrate his 33rd birthday with friends at the Al Noor mosque.

"He lived on the bare basics in order to maximise the money he could send home to support his family," his employer AMT Mechanical said. He leaves behind a wife in Bangladesh, Rina Akter.

He had no family in Christchurch, but in the days it took officials to identify his body, the friends he had made staged a small protest outside the mosque.

"Our brother is missing, give us some information," read one sign.

'He turned my life around'

At times in this city of about 400,000 people it feels like everyone knew a victim, or knows someone who did.

Peter Higgins, 67, says cardiologist Amjad Hamid had convinced him to retire following "a heart attack" and subsequent complications.

BBC

BBC"That bloke really turned my life around," he says of Dr Hamid, a 57-year-old Palestinian who migrated decades ago. "He got shot. And I think, how many people has he saved? And someone decides to play out with a gun."

The tragedy has made many think more deeply about the Muslim community here.

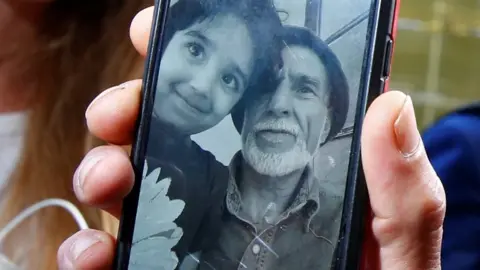

Clare Needham, 72, says Daoud Nabi - the first of the dead to be identified - would turn up frequently to a charity shop where she volunteered, and would haggle over items.

Reuters

ReutersMr Nabi, 70, told her of his deep love for his grandson. It was only this week that she learned the kind of profile he had within the community.

Born in Afghanistan but a long-time New Zealand resident, he was president of a local Afghan association and a known supporter of other migrant groups.

One visitor to the tributes, Dave Palmer, was struck by the tolerance of Farid Ahmed, whose wife was killed in the attack, yet who told reporters he had forgiven the shooter.

"I thought: I don't know whether I could ever do that," says Mr Palmer, a Christian. "That takes an amazing amount of strength and courage."

The kind of tolerance personified by Farid Ahmed and Linda Armstrong stands in stark contrast to the gunman and the online communities through which material allegedly posted by him spread.

Australian Brenton Tarrant, 28, a self-described white supremacist, has been charged with murder.

The gunman live-streamed the massacre on Facebook and a person suspected to be him posted a 65,000-word document online, outlining the alleged reasons for the attacks.

As many have pointed out since, it was littered with coded references that sought to engage specific online communities. It was posted on 8chan - a forum favoured by the alt-right. It showed just how easy it is for intolerance and hate to ignite in such forums, unlike in the wider community, where tolerance is patiently built up over time.

Ultimately, it took just one man and 17 minutes - in the case of the Al Noor attack - to shatter dozens of carefully built, second-chance lives.

Questions have been raised since the attacks about whether forums should be better monitored for evidence of extremism, but experts say this would be challenging for a few reasons - not least the sheer volume of posts.

"We told them our fears about the rise of the alt-right. And the government has not responded adequately," says Anjum Rahman, of the Islamic Women's Council of New Zealand, who says she has been pleading with successive governments to address discrimination.

Ms Rahman is also sharply critical of the media. "Where were you?" she says, arguing there was not enough scrutiny globally.

Paul Hunt, New Zealand's chief human rights commissioner, says it has one of the world's best human rights records although it does see Islamophobia, racism and hate crimes in "some sectors of society".

'He's picked the wrong place'

But if the gunman - whose name Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has sworn she will never speak - had wanted to tear New Zealand apart, judging from the past week he has failed.

On Thursday, the prime minister announced a wide-ranging crackdown on New Zealand's gun laws - including banning all the types of weapons used in the attacks.

Unlike after attacks in the US, for example, it's been almost universally well-received - some people had begun turning in their guns before the ban was even announced.

BBC

BBCAgain and again, locals say they are determined to pull together and ensure this tragedy is not repeated.

"I'm trying to process grief but also anger: how dare he do this to us?" says Cara Butler, 38. "But I think he's picked the wrong place - I think he's going to see the opposite of what he thought. He's not going to create division, it's going to create community and more cohesion."

Mr Syed Ahmed, the survivor, says his two children "have New Zealand, Kiwi values - and I'm so happy with that".

But he fears for them, saying all nations - not just New Zealand - must not become complacent.

"Now I see that people can come to the remotest, peaceful corner of Earth," he says.

"This just can't happen to this country. You can't leave it just as another incident. We're [travelling] as far as the Moon and Mars, but our neighbourhoods aren't safe for our kids?

"It's everyone's responsibility to deal with this hate."

.