Suneung: The day silence falls over South Korea

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAll across South Korea, at exactly 08:40 local time (23:40 GMT Wednesday) on Thursday, more than half a million students take the exam for which they have been preparing their entire lives.

The infamous Suneung, an abbreviation for College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) in Korean, is an eight-hour marathon of back-to-back exams, which not only dictates whether the students will go to university, but can affect their job prospects, income, where they will live and even future relationships.

This year is 18-year-old Ko Eun-suh's first time.

"For us, Suneung is a very important gateway to the future. In Korea, going to university is very important. That's why we spend 12 years preparing for this one day. I know people who've taken this exam up to five times."

Every year in November, Suneung brings the whole country to a standstill.

Silence descends across the capital Seoul as shops are shut, banks close, even the stock market opens late. Most construction work halts, planes are grounded and military training ceases.

Occasionally the stillness is broken by distant sirens - police motorbikes racing to deliver students running late to their exam.

Many nervous parents spend the day at their local Buddhist temple or Christian church, clutching photos of their children - prayers and prostrating are sometimes timed to match the exam schedule.

Lee Jin-yeong, 20, took the Suneung twice before getting into university.

"For about a week before the exam I practised waking up at 06:00, so that my brain would be at its best. I kept telling myself, 'you've studied so hard, now you just need to show them'," she says.

Last year she remembers arriving at the school gate about 07:30. A crowd of delirious first years were singing and chanting, and handing out sticky toffees known as "yeot", for good luck.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut once inside, the mood transformed into solemn silence.

At the entrance to the exam hall, inspectors brandishing metal detectors confiscated all possible distractions, from digital watches, phones and bags to books.

"Everyone was so quiet," says Jin-yeong. "Even the teachers were told to wear trainers so their shoes didn't make any noise that could distract the students."

The writing of the exam itself is shrouded in mystery. Every September, about 500 teachers from across South Korea are selected and driven to a secret location in the mountainous province of Gangwon. For a month, their phones are confiscated and all contact with the outside world is banned.

Eun-suh remembers when her former Chinese language teacher told the class he had previously been selected to help write the test.

"At the time, he told his colleagues he was going travelling. Some teachers even thought he had retired. He was taken to a secret location. For a month he wasn't allowed to leave and he couldn't even contact his family."

Jin-yeong admits she was really nervous last year.

"The test was so difficult. By the end of the Korean language exam, I was so shaken, I couldn't even finish reading the last question. I just guessed."

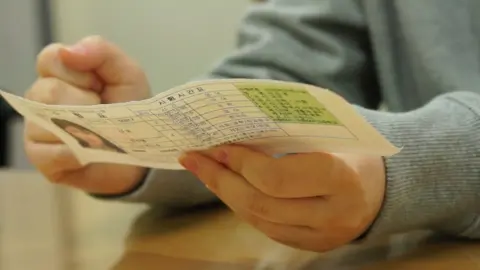

She holds up an old exam attendance card. On the back, it is covered in scribbles and ticks, her answers to a previous year's Suneung.

Officially, every student's individual score is published on a national website, one month after the exam. But bootleg websites, publishing almost immediately after the exam, allow students to compare their total score with the minimum required to get into the university of their choice.

This is how Jin-yeong discovered she had failed.

"When I found out my score was less than what I needed, my heart broke. I felt like I wanted to melt into the ground and disappear."

The following year, Jin-yeong took on Suneung for a second time and, much to her relief, scored enough to make it into university.

But why does such an extreme level of stress surround the university application process?

South Korea has one of the most highly educated populations on the planet. A third of people without a job have a university degree.

With youth unemployment at its highest rate in almost a decade, it has never been harder to get into a good university.

Like many young people in Korea, Eun-suh is not just aiming for a good university, she's aiming for Sky - the collective name for the country's three most prestigious universities, Seoul, Korea and Yonsei. They are seen as the Harvard and Yale, or Oxford and Cambridge, of South Korea.

Some 70% of high school leavers will go to university, but fewer than 2% will reach the dizzy heights of a Sky institution.

"If you want to be recognised, if you want to reach your dreams, you need to go to one of these three universities," says Eun-suh. "Everyone judges you based on your degree and where you got it."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe prestige of attending Sky is also one of the best ways into a job at one of the highly influential family-run conglomerates known as "chaebol", meaning "wealthy clan".

The nation's economy is tied to these few, but huge, sprawling dynasties including LG, Hyundai, SK, Lotte, and the largest of them all - Samsung.

Prof Lee Do-hoon, a sociology teacher at Yonsei University - the Y in Sky, says: "Every year, the national newspapers print how many lawyers, judges and chief executives from the big conglomerates graduate from Sky universities.

"This makes people think, if you go to Sky, you can get a good job. It's why so many parents and students are so eager to go to those universities. But the number of jobs and opportunities within those big firms are actually very few."

Prof Lee explains that graduating from a good university in South Korea does not guarantee young people a good job or a secure wage. The level of competition between applicants is really tough.

"What I hear from my students is that even if you graduate from one of the prestigious colleges, it's getting more and more difficult to get a job. But it's still easier for them, than for students from lower-tier universities.

"Of course, if you don't take the exam and go to university at all, it's nearly impossible to get a good job."

With so much of their future dictated by the outcome of this one single exam, revision starts early.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSince the age of four, Eun-suh, an organised and diligent student, has been preparing for this year's exam.

"I go to school at 07:30 to study by myself. Classes start at 09:00 and last until 17:00. After school, I eat dinner, go to hagwon, then come home around midnight."

"Hagwons", also known as "cram schools", are revision classes led by private tutors, both in person, or online.

There are more than 100,000 hagwons in Korea, and with more than 80% of all Korean children, both primary and secondary, attending a cram school, it is a $20bn (£15.4bn) industry. Some of the country's top celebrity teachers earn millions every year.

Eun-suh goes to hagwon six times a week for extra maths and English lessons. Then even at the weekend she studies, normally at a "dokseosil", or revision room.

"Dokseosils are usually dark. They are designed to make you study alone, so each cubicle is surrounded by long curtains. You go in, turn on your lamp and study," she explains.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSuneung was once seen as a source of social mobility, a way for poorer students to access a university education. However, the pressure on parents to fork out thousands per month on private tuition is leaving poorer families behind.

Experts such as Prof Lee believe such escalating costs are also one of the main reasons why South Korea's birth rate is the lowest in the world.

"This high cost of preparing kids to go to college is one of the main reasons we are experiencing low fertility rates. It's about quality over quantity. Parents would rather invest more in a small number of children."

Successive governments have tried to rein in the cram school industry, both for the sake of the parents' pockets, but also out of concern for student wellbeing.

Today by law, cram schools in Seoul are meant to close no later than 22:00, they cannot teach any material ahead of mainstream schools and fees have been capped.

But for Prof Lee, it is simply not enough.

"The problem is even with all these changes, the private side of education is so dominant in Korea. It's so common to send students to cram school and private tutoring that those with more money are still more likely to get into a prestigious university."

Another criticism of Suneung is the huge burden on students' mental wellbeing.

Dr Kim Tae-hyung, a psychologist working in Seoul, says: "Korean children are forced to study hard and compete with their friends.

"They are growing up alone, just studying by themselves. This kind of isolation can cause depression and be a major factor in suicide."

Globally, suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people, but in South Korea it is the number one cause of death for young people aged between 10 and 30.

The country also has the highest levels of stress among young people aged 11 to 15 compared with any other industrialised country in the world, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Dr Kim says the pressure in Korean society to go to a good university and get a good job begins early.

"Children are feeling nervous from a very young age. Even first-year elementary students talk about which job pays the most."

Prof Lee thinks his nation's obsession with educational achievement, but also rising unemployment, are the main reasons so many young people in Korea are struggling.

"I think the high suicide rate is being driven by an increasing gap between the lack of employment opportunities, and students' own expectations of success. There is also a lack of coping strategies to handle the stress."

However, many experts emphasise educational pressures are not the only cause. The rapid growth of cities, as well as a decline in traditional close-knit family structures, have also been attributed to increased feelings of isolation, depression and suicide.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor more than a decade, the government has been attempting to tackle the nation's poor mental health by investing in advertising campaigns, setting up national helplines and opening up more hospital beds in psychiatric wards.

But unlike almost all other OECD countries, over the past decade, the suicide rate in Korea has continued to increase.

The government has also attempted to overhaul Suneung by allowing students to gain university entrance points in other ways, such as mentoring or volunteering. But for Eun-suh, this has only made the process more stressful.

"There are now other ways of collecting extra points, but in practice this just makes it all the more confusing, because there are now more things to worry about. We need to achieve it all, including extra-curricular activities, volunteering, mentoring, and other school exams."

By the weekend, Eun-suh will know whether she has achieved her dream of getting into a Sky university.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe says she just needs to control her nerves.

"Every time I get my mock exam results, I get depressed. I ask myself, 'can I go to the university I want?'. I might be happy with my own ranking compared to the rest of my school, but when I compared myself to the rest of the country, I get scared. Too scared to even show my mum."

But for Jin-yeong, now at university, she can look back with confidence.

"When I watch foreigners on YouTube trying to solve the questions from Suneung, they find it so hard.

"From the outside, I know it looks difficult, but it's not as scary as you might think," she says. "Instead of pitying us, I wish foreigners would think how awesome we are."

Updated on 26 November 2018: Eun-suh passed her exam with enough points to go to university. She is now applying to study sociology.

For support on mental health visit the BBC Advice pages or for help in Korean visit Lifeline