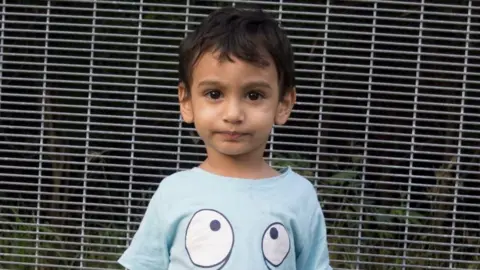

Nauru refugees: The island where children have given up on life

World Vision Australia

World Vision AustraliaSuicide attempts and horrifying acts of self-harm are drawing fresh attention to the suffering of refugee children on Nauru, in what is being described as a "mental health crisis".

The tiny island nation, site of Australia's controversial offshore processing centre, has long been plagued with allegations of human rights abuses.

But a series of damning media reports recently has also highlighted a rapidly deteriorating situation for young people.

"We are starting to see suicidal behaviour in children as young as eight and 10 years old," says Louise Newman, professor of psychiatry at the University of Melbourne who works with families and children on the island.

"It's absolutely a crisis."

A loss of hope

Australia intercepts all asylum seekers and refugees who try to reach its shores by boat. It insists they will never be able to resettle in Australia, so over the years has sent many to privately run "processing centres" it funds on Nauru and in Papua New Guinea.

Groups working with families on Nauru paint a brutal picture of life for children on the island. Many have lived most of their life in detention, with no idea of what their future will be.

The trauma they have endured, coupled with poor - and often dangerous conditions - contribute to a sense of hopelessness.

Natasha Blucher, detention advocacy manager at the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC), was unable to share details of specific cases with the BBC due to privacy and safety concerns.

But she said ASRC works with about 15 children who have either made repeated suicide attempts or are regularly self-harming.

She also believes the problem has reached crisis point.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesASRC, like most advocates and medical professionals, assist families on Nauru remotely as access to the island is heavily restricted.

It estimates at least 30 children are suffering from traumatic withdrawal syndrome - also known as resignation syndrome. It's a rare psychiatric condition where sufferers, as a response to severe trauma, effectively withdraw from life.

The condition can be life-threatening as victims become unable to eat and drink.

"Around three months ago we were seeing a smattering of this... then over that period it seems to have proliferated," Ms Blucher told the BBC.

What is traumatic withdrawal syndrome?

- It is a progressive, deteriorating condition most commonly seen in children and that can be life threatening.

- Begins with disengagement from enjoyable activities such as playing or drawing and progressively worsens. Sufferers may begin to refuse food and drink.

- In the worst cases a sufferer will become unresponsive, unable to speak and their body will begin to shut down.

- Treatment, which can take months, requires access to paediatric intensive care.

- A large outbreak was observed in group of asylum seekers in Sweden.

Children feel 'unsafe'

Prof Newman, a former advisor to the Australian government on the mental health of asylum seekers, says the outbreak of this very serious condition is particularly concerning.

"In many ways it's not surprising… they are exposed to a lot of trauma there [and] a sense of hopelessness and abandonment. They feel very unsafe".

Another physician assisting with children's cases is GP Barri Phatarfod. Her organisation Doctors 4 Refugees has not been allowed to visit Nauru but receives referrals from advocates for assessment and advice. She says of the 60 cases referred to her organisation, every child has some mental health impairment.

"It's impossible not to," she says. "They witness suicide attempts almost daily as well as sexual harassment and physical and sexual abuse and there is no prospect of release."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt present most cases involve children from Iran, as well as kids from Iraq, Lebanon and Rohinyga.

Dr Phatarfod adds that children as young as three are "displaying inappropriately sexualised behaviour - behaviour that typically only comes from having this acted upon themselves".

A divisive policy

One key proponent of the policy was the country's new prime minister, Scott Morrison, who rose to national prominence as a hardline immigration minister. Mr Morrison was one of the toughest enforcers of the divisive "Stop the Boats" policy and years later, becomes leader as unease over the treatment of asylum seekers hasn't abated.

Supporters argue the policy has been highly effective, resulting in a dramatic drop in illegal boat arrivals. The government said a vessel that made land this week was the first boat carrying illegal asylum seekers to reach Australia since 2014.

But critics point to the huge physical and mental toll exacted on the people placed in offshore detention facilities.

World Vision Australia

World Vision AustraliaIn 2015, the site on Nauru became an "open centre," meaning residents can come and go as they please.

But this has done little to improve life for children on the island. The tiny Pacific island is just 21 sq km (8 sq miles) and covered with phosphate rocks. It was mined heavily and has few trees or animals. Advocates say even though the camp is technically open, there are few places for people to go.

Access to care

As the children's health crisis worsens, a coalition of human rights groups has demanded the Australian government remove the 119 asylum seeker children off Nauru and resettled them elsewhere.

In a statement, the Australian government said it "takes seriously its role in supporting the Government of Nauru to ensure that children are protected from abuse, neglect or exploitation".

"A range of care, welfare and support arrangements are in place to provide for the needs of children and young people," it said.

Medical services including a hospital are available on Nauru but experts say they are inadequate. If a person needs more complex treatment, a referral must be made to the Nauruan government to have them transferred overseas for care.

"When a person cannot receive appropriate treatment for a significant health condition in Nauru, the person is offered treatment in Taiwan, Papua New Guinea or Australia. Those cases are referred to the Department by the person's treating clinician," the Australian government said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStill, many argue the system of referrals is failing children on Nauru. Advocates say the process is too slow, and they are overwhelmed by the volume of children experiencing mental health problems.

Jennifer Kanis, head of the social justice practice at law firm Maurice Blackburn, is leading several cases to bring urgent medical care to young people on the island. She believes that even though these children have never entered Australian territory, the Australian government has a duty of care.

"It devastating… that we have to take legal action to get proper medical care for these kids," Ms Kanis says.

"The government is more concerned with their policy of keeping this cohort of people seeking asylum off Australia than they are with their health."