Why are UK and US sending more troops to Afghanistan?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPrime Minister Theresa May has announced that 440 more British military personnel will join the Nato mission in Afghanistan. But how do the UK and US allies see their role in the country?

The additional troops will be ferrying international advisors safely around the country's capital city, Kabul, in their Foxhound vehicles in what has been dubbed "Armoured Uber". All part of the Nato mission to train, advise and assist the Afghan security forces.

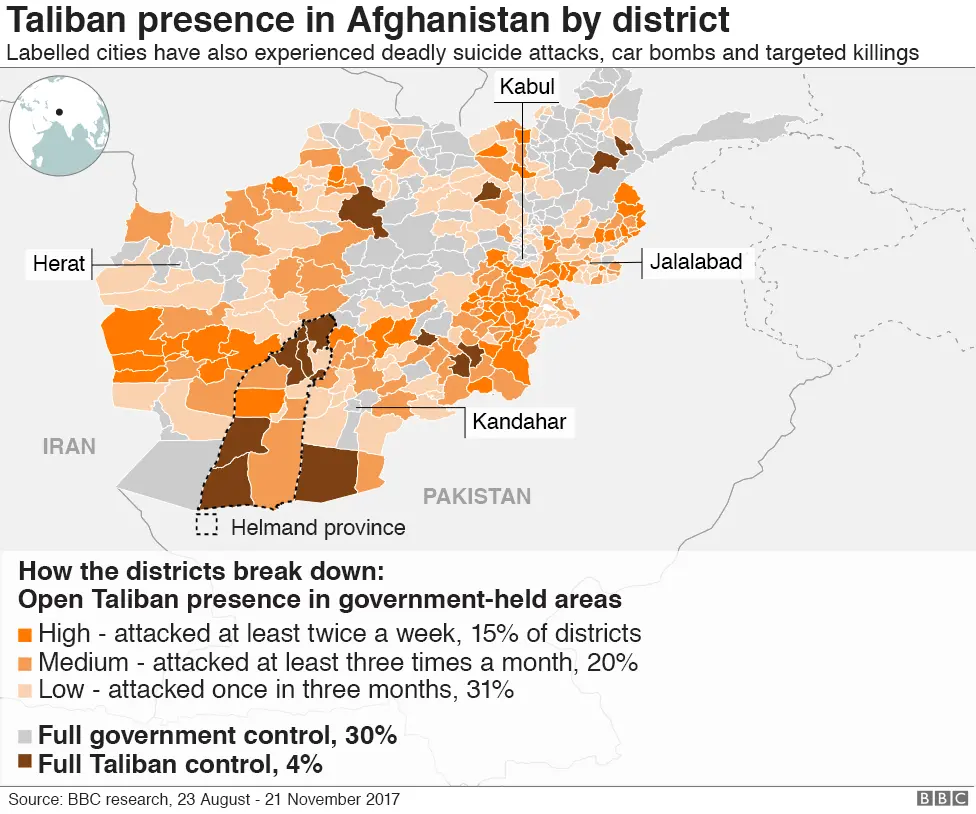

For British soldiers and most of Nato's forces it is no longer a combat mission. It's now almost four years since British troops left the heat and dust of Afghanistan's Helmand province. It's where hundreds lost their lives. Today the Taliban still control most of Helmand.

Two years ago, the Americans returned, albeit in smaller numbers than previously served in the province. It's a return, too, for their commander, Brig Gen Ben Watson, who was last in Helmand in 2010. He says: "I'm not surprised we're still committed here in some fashion."

He calls the decision in 2014 by US and British forces to leave "premature". And if the Americans had not returned, he says: "I would imagine that Helmand would be pretty solidly under the Taliban right now."

Gen Watson now commands about 500 US Marines who, we are repeatedly told, are not there to lead the fight, but to "advise and assist" the Afghan forces. That support includes US air strikes against Taliban positions, which are also targeted with the Marines' ground-based long-range HIMARS artillery rockets. It also means overseeing the training of the Afghan army, whose troops need all the help they can get.

The Afghan army has been struggling to fill its ranks because of the reluctance of men to serve. Nowhere more so than in Helmand.

The unit we saw being trained was already significantly under-strength. They'd been pulled off the battlefield after almost two years of "intense fighting". We were told they'd suffered high rates of attrition - a mixture of casualties and desertions.

Recent recruits had been added to their number. Often, the first time they know they're being sent to Helmand is when they get on a plane in Kabul.

Lt Col Jon Connelly, the US Marine overseeing the training of this unit, says it is still "70% below strength". I ask him if that's a worry. "It is," he says, but with "time and recruiting and constant advising the senior leadership will improve the situation".

They may be short on numbers but there have been improvements in the overall quality of the Afghan security forces. They do now have their own fledgling air force and effective elite combat units. Overall, the Afghan army also appears to be better trained and equipped. But there's still a long way to go.

We went out on patrol with them on the main route through Helmand - Highway 1. The road is often targeted by Taliban roadside bombs. But some of our escorts seemed more interested in their entertainment along the way, with Bollywood hits piped through a stereo speaker. Some were smoking cannabis. They still don't always look, sound or even smell like a professional army.

But hope hasn't completely shrivelled in the intense heat of Helmand. Gen Watson says he'd "never go so far [as] to say we've turned a corner" but recent events have shown "possibilities we've never seen before".

That sense of optimism is even more palpable in the capital, Kabul. It's born out of a recent three-day ceasefire over Eid, the festival marking the end of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. It's the first time there's been a pause in the fighting in 17 years of war.

In that brief respite, Taliban fighters entered the city and mingled with their enemy - the Afghan security forces. The two sides even posed together, smiling for the cameras.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLt Gen Richard Cripwell, the most senior British military officer in Afghanistan, describes it as an "extraordinary moment".

He says there's now an opportunity for peace "that was almost unimaginable six months ago". "There's a body of the Taliban that wants to be part of the future of their country."

Britain's ambassador to Afghanistan, Sir Nicholas Kay, says the ceasefire was without precedent and a sign that Afghans "are talking more and more about peace". "No-one," he adds, "is talking about fighting their way to victory any more."

The overall commander of Nato forces in the country, the US's Gen John Nicholson, describes the scenes as an "almost universal outpouring of support for peace".

That sounds like a wildly optimistic statement. But he tells me the key elements for talks now exist - namely, the offer to the Taliban from the US for direct talks and a discussion about international troop numbers. He says: "The ground is closing between the two sides."

There is some evidence to suggest that might be happening. Just over a week ago, a senior US diplomat held secret talks with Taliban officials in Doha. It follows a push by the Trump administration to engage directly with the militants. It's been described as a preliminary discussion.

But the reality is there's still no "peace process". An attempt to prolong the truce by the Afghan government, with a further 10-day ceasefire, was ignored by the Taliban.

The Taliban have shown little desire to engage in talks with President Ashraf Ghani's government, which they still view as a puppet of the US. Nor are the Taliban the only ones involved in the fight.

The group calling itself Islamic State now has a hold in the east of the country. They've been responsible for a spate of suicide attacks.

While Britain may have turned its back on Helmand, it hasn't given up on Afghanistan. There is still international resolve. Sir Nicholas Kay says: "The strategy is working."

But then again that's exactly what I heard so many times from so many senior British army officers during their time in Helmand.

After 17 years of fighting, peace is still just a hope, not a fact, in Afghanistan.