International Criminal Court judges consider Afghanistan war crimes inquiry

BBC

BBCJudges at the International Criminal Court (ICC) are deciding whether to authorise an official war crimes inquiry into events in Afghanistan.

They are due to begin examining written submissions from victims in Afghanistan about whom and what any potential investigation should focus on.

In 2017, ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said there was a "reasonable basis to believe" war crimes had been committed.

Possible perpetrators included the Taliban, CIA and Afghan forces.

Warning: some readers may find some of the details below distressing.

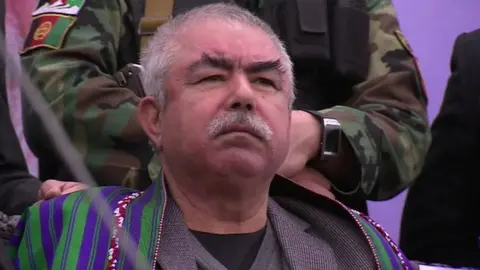

The BBC has learnt that one of the most high-ranking officials to be named in the submissions to the court is Gen Abdul Rashid Dostum. Claims of human rights abuses have dogged the current vice-president of Afghanistan for decades.

He is currently in Turkey in de facto exile after one particularly grim allegation.

In late 2016, Ahmad Eshchi, a political rival of Gen Dostum, said he had been beaten and sodomised on his orders.

"He told his guards, 'Rape him until he bleeds and film it'," Mr Eshchi told the BBC. "They put a Kalashnikov [rifle] into my anus. I was screaming in pain."

Gen Dostum refused to appear in court in Afghanistan. In May 2017 he travelled to Turkey for medical treatment. Some analysts believe the Afghan government pressured him to leave.

Gen Dostum attempted to return to Afghanistan in July of last year but his plane was refused permission to land.

Because he is still in Turkey, Mr Eshchi believes the ICC needs to step in.

"It's been 14 months and Dostum still hasn't answered any questions about this," he said. "As time goes on I am losing hope that the government here will ever bring him to justice."

Gen Dostum's spokesman has previously denied that Mr Eshchi was detained or sexually assaulted by anyone connected to Dostum.

Bereaved by the Taliban

Others in Afghanistan are hoping the ICC can help hold the insurgent groups in the country to account.

Samara, 32, was a cook at an orphanage in Kabul. She died after being caught in a Taliban suicide bombing in July 2017.

Her daughter, 17-year-old Fatima, told the BBC about the moment she found out: "I heard on the news that there had been a suicide attack. I called my mum's phone but a policeman answered. He said he had found it at the scene of the blast."

Fatima is one of those who have written to the ICC. She does not believe the Afghan authorities will give her family justice.

"Whenever they announce on the TV they've arrested someone and brought him to court, they release him a few days later, and the bombings continue," she says.

Despite the risks, Fatima says she is not afraid of speaking out.

"My mother fought against my other relatives and social pressure to let me join a football team, and to learn the guitar," she says. "She did so much for me. Now it's my turn to fight for her."

Fatima also wants the ICC to investigate the Afghan government for its failure to stop the attacks. It seems unlikely that that would fall under the remit of the ICC though. And bringing the Taliban to justice would not necessarily be an easy task.

Guantanamo submissions

Philippe Sands QC is the director of the Centre on International Courts and Tribunals at University College London.

"You have got to catch the Taliban and you need evidence," he says. "Evidence comes in the form of documents, in the form of witness statements and that gathering exercise for an institution without its own police force is incredibly problematic.

"The court has a policy of only going after upper-echelon individuals - they don't want the foot soldiers. So you've got to apprehend those people."

AFP

AFPThe proposed investigation by the ICC would cover events from May 2003 onwards, when Afghanistan signed up to the court. Any alleged crimes committed in the country after that date are eligible to be investigated, even if by foreign nationals.

That means the alleged torture of some prisoners in Bagram detention centre before they were transferred to Guantanamo Bay would also be covered.

The detention centre was originally built and run by the Americans but later handed over to Afghan control.

The charity Reprieve is making submissions to the ICC on behalf of a number of current and former Guantanamo Bay detainees.

Maya Foa, director of Reprieve, told the BBC the alleged abuses detainees suffered at Bagram included "Russian roulette with guns, men held in stress positions for days… Abuses which destroyed the men both physically and mentally".

"These abuses were perpetrated at the behest of top commanders," she said. "The kinds of people the ICC are trying to target."

American officials have said that whilst they support attempts to bring the Taliban to justice, they believe an ICC investigation would be "unwarranted and unjustified". The United States is not a signatory to the ICC.

In 2002 Congress passed the American Service-Members Protection Act, which allowed the US authorities to "free" US personnel detained for trial in the ICC by "all means necessary".

That makes successful prosecutions of American officials extremely difficult. But the ICC is under pressure to show that it can take on politically sensitive cases. Up until now it has focused on incidents in Africa.

Why only Africans?

UCL's Philippe Sands told the BBC: "On the website of the ICC everyone indicted is African and black or both.

"That's a problem because Africans don't have a monopoly on international crime.

"That has caused a backlash. African countries are saying, 'Why focus on us? Look at what is going on around the world.'"

The ICC judges still need to decide whether to authorise a formal investigation, let alone level charges, but many in Afghanistan are looking to the court to provide some kind of justice after years of violence.