Reality Check: Does China's Communist Party have a woman problem?

AFP

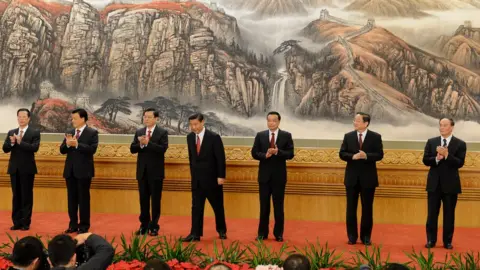

AFPAt the end of the Chinese Communist Party's 19th Congress, the new Politburo Standing Committee was revealed: seven middle aged men in dark suits, without a woman to be seen. There has never been a female member of the Standing Committee.

Of the 2,280 delegates at that Congress, fewer than a quarter were women.

That's got some people asking whether the party should take gender equality more seriously. The New York Times wrote of women being "shut out" - but does the Chinese Communist Party have a woman problem?

Of the 89.4 million members of the Chinese Communist Party, just under 23 million are women - that's 26%.

And women make up 24% of China's National Congress - the sprawling national parliament. You don't have to be a Communist Party member to sit on that.

Women are less represented the higher up the political tree you climb.

After the last Congress in 2012, only 33 women sat on the Central Committee which elects the powerful Politburo - that's 9%.

Only two of the 25 members of that Politburo were women - 8%.

AFP

AFPIt's evidently difficult for Chinese women to break through the political glass ceiling. That's despite the government's stated commitment to gender equality, and despite the fact that more women than men are entering university in China.

What's holding them back?

Women usually join the party at university or when they join the workforce as a way of advancing their careers.

However, promotion beyond county and township level is especially difficult.

"The long-standing perception that women's place belongs at home and in the kitchen mean they are not meant to be ambitious," explains Professor Lynette H. Ong, Professor of Political Science at University of Toronto.

"Their societal role is to be caregivers to the husbands, children and grandchildren.

"Even though Mao once famously said, 'Women hold up half the sky', women still have a long way to go in their fights for equal representation."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTop-level

Women are also hindered because there is little chance of receiving a national appointment without first holding a provincial government or party position - it takes time to climb that ladder.

A number of women reach mid-level executive positions. However, comparatively few reach a top-level leadership position.

"One needs to build good guanxi (connection) with the people who have the power to appoint and they are predominantly men," explains Dr Ling Li, Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna.

A lower national retirement age for women also hinders the opportunity for promotion. China's national retirement age is currently 60 years old for men, 55 for female civil servants and state enterprise employees, and 50 for all other female workers.

AFP

AFPSome feel the government should be more proactive.

"There is inadequate state intervention to implement policies to alleviate some of the barriers to women's progression in politics. Quota requirements have had the opposite effect because of the way they have been interpreted," explains Prof Jude Howell, Director for the Centre for Civil Society at the London School of Economics.

But is the situation in China unusual? Are Chinese women any worse off than women elsewhere in the world?

Not really.

Women out of power

Comparing the work women do in China's National Congress to the work of British MPs or US Congresswomen is like comparing apples with pears.

But one thing is clear - women make up small percentages of political decision-making bodies around the world, not only in China.

They make up only 32% of MPs in the UK's House of Commons - and that's a record high.

They account for only 11% of members of India's Lok Sabha and 9% of Japan's House of Representatives.

There are some countries with a much better record - women sit in 61% of the seats in Rwanda's Chamber of Deputies, and in communist Cuba, make up 49% of the Asamblea Nacional.

So much for women at the top. How about the grass roots?

Remember, 26% of Communist Party members are women.

But that's unremarkable when you look at ruling parties around the world.

Vietnam and Cuba are also one-party states. In the last available figures for both countries, fewer than 33% of party members are women.

That picture is similar in some multi-party democracies.

Women make up 26% of Angela Merkel's CDU party in Germany, and around 30% of Theresa May's Conservatives in the UK.

Meanwhile, a survey carried out by the University of Sao Carlos suggests that 33% of all party members in the Brazilian state of Sao Paolo are female.

So while women are under-represented in Chinese politics, the issue is not China's alone.