UN failures on Rohingya revealed

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UN leadership in Myanmar tried to stop the Rohingya rights issue being raised with the government, sources in the UN and aid community told the BBC.

One former UN official said the head of the UN in Myanmar (Burma) tried to prevent human rights advocates from visiting sensitive Rohingya areas.

More than 500,000 Rohingya have fled an offensive by the military, with many now sheltering in camps in Bangladesh.

The UN in Myanmar "strongly disagreed" with the BBC findings.

In the month since Rohingya Muslims began flowing into Bangladesh, the UN has been at the forefront of the response. It has delivered aid and made robust statements condemning the Burmese authorities.

But sources within the UN and the aid community both in Myanmar and outside have told the BBC that, in the four years before the current crisis, the head of the United Nations Country Team (UNCT), a Canadian called Renata Lok-Dessallien:

- tried to stop human rights activists travelling to Rohingya areas

- attempted to shut down public advocacy on the subject

- isolated staff who tried to warn that ethnic cleansing might be on the way.

One aid worker, Caroline Vandenabeele, had seen the warning signs before. She worked in Rwanda in the run-up to the genocide in late 1993 and early 1994 and says when she first arrived in Myanmar she noticed worrying similarities.

"I was with a group of expats and Burmese business people talking about Rakhine and Rohingya and one of the Burmese people just said 'we should kill them all as if they are just dogs'. For me, this level of dehumanisation of humans is one sign that you have reached a level of acceptance in society that this is normal."

For more than a year I have been corresponding with Ms Vandenabeele, who has served in conflict areas such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Rwanda and Nepal.

Between 2013 and 2015 she had a crucial job in the UNCT in Myanmar. She was head of office for what is known as the resident co-ordinator, the top UN official in the country, currently Ms Dessallien.

The job gave Ms Vandenabeele a front-row seat as the UN grappled with how to respond to rising tensions in Rakhine state.

Back in 2012, clashes between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists left more than 100 dead and more than 100,000 Rohingya Muslims in camps around the state capital, Sittwe.

Since then, there have been periodic flare-ups and, in the past year, the emergence of a Rohingya militant group. Attempts to deliver aid to the Rohingya have been complicated by Rakhine Buddhists who resent the supply of aid for the Rohingya, at times blocking it and even attacking aid vehicles.

Reuters

ReutersIt presented a complex emergency for the UN and aid agencies, who needed the co-operation of the government and the Buddhist community to get basic aid to the Rohingya.

At the same time they knew that speaking up about the human rights and statelessness of the Rohingya would upset many Buddhists.

So the decision was made to focus on a long-term strategy. The UN and the international community prioritised long-term development in Rakhine in the hope that eventually increased prosperity would lead to reduced tensions between the Rohingya and the Buddhists.

For UN staff it meant that publicly talking about the Rohingya became almost taboo. Many UN press releases about Rakhine avoided using the word completely. The Burmese government does not even use the word Rohingya or recognise them as a distinct group, preferring to call them "Bengalis".

During my years reporting from Myanmar, very few UN staff were willing to speak frankly on the record about the Rohingya. Now an investigation into the internal workings of the UN in Myanmar has revealed that even behind closed doors the Rohingyas' problems were put to one side.

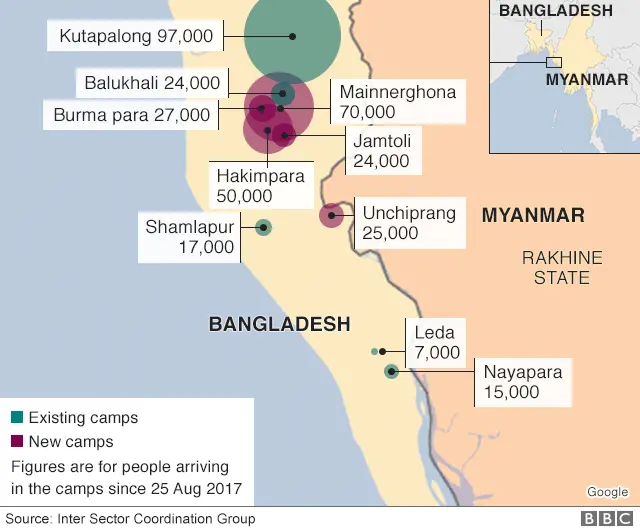

Where have the Rohingya fled to

Multiple sources in Myanmar's aid community have told the BBC that at high-level UN meetings in Myanmar any question of asking the Burmese authorities to respect the Rohingyas' human rights became almost impossible.

Ms Vandenabeele said it soon became clear to everyone that raising the Rohingyas' problems, or warning of ethnic cleansing in senior UN meetings, was simply not acceptable.

"Well you could do it but it had consequences," she said. "And it had negative consequences, like you were no longer invited to meetings and your travel authorisations were not cleared. Other staff were taken off jobs - and being humiliated in meetings. An atmosphere was created that talking about these issues was simply not on."

Repeat offenders, like the head of the UN's Office for the Co-ordination for Humanitarian Assistance (UNOCHA) were deliberately excluded from discussions.

Ms Vandenabeele told me she was often instructed to find out when the UNOCHA representative was out of town so meetings could be held at those times. The head of UNOCHA declined to speak to the BBC but it has been confirmed by several other UN sources inside Myanmar.

Ms Vandenabeele said she was labelled a troublemaker and frozen out of her job for repeatedly warning about the possibility of Rohingya ethnic cleansing. This version of events has not been challenged by the UN.

Attempts to restrict those talking about the Rohingya extended to UN officials visiting Myanmar. Tomas Quintana is now the UN special rapporteur for human rights in North Korea but for six years, until 2014, held that same role for Myanmar.

Speaking from Argentina, he told me about being met at Yangon airport by Ms Dessallien.

"I received this advice from her - saying you should not go to northern Rakhine state - please don't go there. So I asked why and there was not an answer in any respect, there was just the stance of not trying to bring trouble with the authorities, basically," he said.

"This is just one story, but it demonstrates what was the strategy of the UN Country Team in regards to the issue of the Rohingya."

Mr Quintana still went to northern Rakhine but said Ms Dessallien "disassociated" herself from his mission and he didn't see her again.

One senior UN staffer told me: "We've been pandering to the Rakhine community at the expense of the Rohingya.

"The government knows how to use us and to manipulate us and they keep on doing it - we never learn. And we can never stand up to them because we can't upset the government."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UN's priorities in Rakhine were examined in a report commissioned by the UN in 2015 entitled "Slippery Slope: Helping Victims or Supporting Systems of Abuse".

Leaked to the BBC, it is damning of the UNCT approach.

"The UNCT strategy with respect to human rights focuses too heavily on the over-simplified hope that development investment itself will reduce tensions, failing to take into account that investing in a discriminatory structure run by discriminatory state actors is more likely to reinforce discrimination than change it."

There have been other documents with similar conclusions. With António Guterres as the new secretary general in New York, a former senior member of the UN was asked to write a memo for his team in April.

Titled "Repositioning the UN" the two-page document was damning in its assessment, calling the UN in Myanmar "glaringly dysfunctional".

In the weeks that followed the memo, the UN confirmed that Ms Dessallien was being "rotated" but stressed it was nothing to do with her performance. Three months on Ms Dessallien is still the UN's top official there after the Burmese government rejected her proposed successor.

"She has a fair view and is not biased," Shwe Mann, a former senior general and close ally of Myanmar's de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi, told me. "Whoever is biased towards the Rohingyas, they won't like her and they will criticise her."

Ms Dessallien declined to give an interview to the BBC to respond to this article.

The UN in Myanmar said its approach was to be "fully inclusive" and ensure the participation of all relevant experts.

"We strongly disagree with the accusations that the resident co-ordinator 'prevented' internal discussions. The resident co-ordinator regularly convenes all UN agencies in Myanmar to discuss how to support peace and security, human rights, development and humanitarian assistance in Rakhine state," a statement from a UN spokesperson in Yangon said.

On Tomas Quintana's visits to Rakhine, the spokesperson said Ms Dessallien had "provided full support" in terms of personnel, logistics and security.

Ten ambassadors, including from Britain and the United States, wrote unsolicited emails to the BBC when they heard we were working on this report, expressing their support for Ms Dessallien.

There are those who see similarities between the UN's much-criticised role in Sri Lanka and what has happened in Myanmar. Charles Petrie wrote a damning report into the UN and Sri Lanka, and also served as the UN's top official in Myanmar (before being expelled in 2007).

He said the UN's response to the Rohingya over the past few years had been confused and that Ms Dessallien hadn't been given the mandate to bring all of the key areas together.

"I think the key lesson for Myanmar from Sri Lanka is the lack of a focal point. A senior level focal point addressing the situation in Myanmar in its totality - the political, the human rights, the humanitarian and the development. It remains diffuse. And that means over the last few years there have been almost competing agendas."

So might a different approach from the UN and the international community have averted the humanitarian disaster we are seeing now? It's hard to see how it might have deterred the Burmese army's massive response following the 25 August Rohingya militant attack.

AFP

AFPMs Vandenabeele said she at least believed an early warning system she proposed might have provided some indications of what was about to unfold.

"It's hard to say which action would have been able to prevent this," she told me. "But what I know for sure is that the way it was done was never going to prevent it. The way it was done was simply ignoring the issue."

Mr Quintana said he wished the international community had pushed harder for some sort of transitional justice system as part of the move to a hybrid democratic government.

One source said the UN now appeared to be preparing itself for an inquiry into its response to Rakhine, and this could be similar to the inquiry that came after the controversial end to Sri Lanka's civil war - and which found it wanting.