What are North Korea's other WMDs?

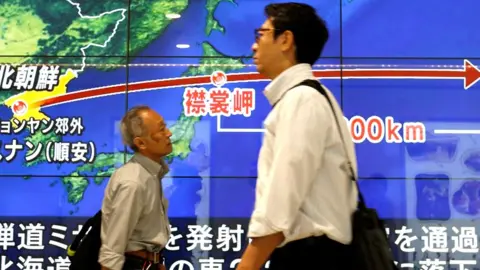

Reuters

ReutersThe warning from the South Korean President Moon Jae-in of the potential threat from North Korean chemical and biological weapons is timely, underscoring that Pyongyang has invested heavily in a variety of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programmes.

Mr Moon also warned of the danger of a North Korean electro-magnetic pulse (EMP) attack that could cripple a country's electrical grid and critical infrastructure.

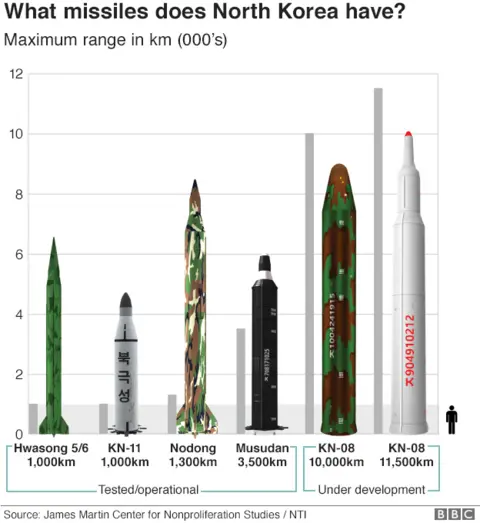

So while attention focuses on Pyongyang's nuclear weapons programme and the long-range missiles capable of delivering a nuclear warhead, how much do we know about these other secretive WMD programmes?

North Korea makes no secret of its nuclear weapons ambitions. In marked contrast, it does not admit to having chemical or biological weapons. It has signed up to a treaty banning biological weapons, but it has not acceded to the equivalent agreement banning chemical weapons.

US and South Korean experts believe that, in fact, North Korea does have a significant chemical weapons programme, with stockpiles of munitions containing nerve, choking and blister agents; such substances as phosgene; hydrogen cyanide; mustard; and sarin.

North Korea has a huge artillery and rocket force capable of delivering such munitions, though it remains unclear if it is able to produce chemical warheads that would survive the stresses of a flight on a ballistic missile.

Much less is known about North Korea's activities in the biological weapons field. South Korean intelligence believes that the North is well-able to produce and weaponise pathogens like anthrax, botulism and typhus, but it is far from clear if these programmes have gone beyond the research stage.

The EMP threat is something that is widely written about - it has especially been taken up in US conservative circles - and the debate has gained added currency in the wake of North Korean threats to mount such an attack.

In essence, this would involve the detonation of a small nuclear device in the atmosphere - you would not even need a nuclear missile, a balloon could be released from a cargo ship - which results in a massive power-surge that damages and disables electrical circuitry over a huge area.

Crippled infrastructure that might not be repairable for months could lead to death, chaos and lawlessness on a vast scale. In 2008, a US commission investigating the threat concluded that "the electromagnetic pulse generated by a high-altitude nuclear explosion is one of a small number of threats that can hold our society at risk of catastrophic consequences".

Experts differ on the likelihood of such an attack emanating from North Korea, whatever the threats. Of course, in the Korean context there is already a nuclear threat and, to the extent that an EMP attack involves the detonation of a nuclear device, Pyongyang would be risking catastrophic reprisal and potentially the end of the regime.

All these fears underscore the problem of dealing with Pyongyang. There is a tension between keeping the international community united behind UN sanctions resolutions and applying the scale of pressure that the Trump administration wants (and which it believes can only come from China).

In the meantime, North Korea's programmes advance. A senior US general now warns that Pyongyang's recent test may well have been a hydrogen bomb, marking a significant advance in the North's capabilities.

And all the while, the danger of a test going wrong - of debris landing on Japan or Guam - or of miscalculation grows, and with that the threat of crisis turning into conflict.