What's life like on the border with North Korea?

BBC

BBCIt's one in the morning and, under the neon lights of Seoul's shining skyscrapers, people are laughing and chatting, heading to eat barbecue or drink tiny glasses of soju, the country's national alcoholic drink.

Being just 35 miles from one of the world's most dangerous borders isn't playing on the mind of anyone here tonight.

For me, that's one of the most striking things about the mood in South Korea right now. The swirling fear that's enveloping other parts of the globe isn't in evidence here. People know this threat, they recognise it, but they've lived with it for a long time already.

The conflict between North and South Korea is nothing new. Technically the two countries are still at war, and simply living in a state of armistice. So why has world attention - and fear - grown so fast in the past few months?

In Seoul, people's response to the North Korean threat tends to fall along generational lines. For those who are too young to remember the Korean War, it feels like more of an abstract threat. While they can't see it, and it has no effect on their daily lives, they spend little time worrying about it.

The Korean peninsula is a place of contrast. In just a few decades, the South has clawed its way back from almost complete destruction to become the fourth-largest economy in Asia.

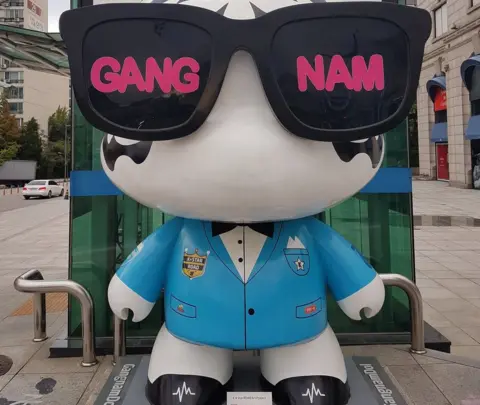

I wandered through the Gangnam district packed with colourful statues celebrating the booming K-pop music scene. Even after midnight half the floors in Samsung's towering glass headquarters had lights on and people at their desks. This prosperity is born of hard graft.

There's no outward show of wealth in the North. Driving along the border, hearing the heavy thumps of South Korean army target practice and the return of clattering gunfire from the North, two worlds are colliding.

A quick check of my smartphone map app shows a featureless expanse. No roads, no towns. What goes on here is shadowy and secretive.

I travelled to the closest village to the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ), just three miles from the barbed wire. Its men have special permission to farm inside the DMZ, and one of them, sprightly 77-year-old Mr Ong, showed me where he'd lost every toe on his right foot standing on a landmine.

He described the day he heard a bang and looked down to see his leg mangled and twisted. Even then he felt lucky, nine men in his village had stood on mines and he was the only one of them to survive.

Unlike in Seoul, where underground stations and housing block basements double-up as emergency shelters, this place has a clean, new, purpose-built bunker sunk two storeys below ground behind an 8in (20cm) thick door.

In one corner, stands a row of shelves, neatly stacked with clear plastic boxes. Inside, lie pristine escape hoods, hammers, first aid supplies, a torch, a whistle - all lined up and ready to be used in case of an emergency.

They're so untouched that I ask if they've ever even been practised with. "We haven't had a real emergency yet," says Mr Lee, the village elder in charge of the shelter. "If we need them, there are directions on the wall."

Does this lack of urgency suggest the threat of imminent war has been overblown? "I am worried," he replies, "just last week someone from the city came to check on us."

Many analysts, though, believe Pyongyang has its eye on prizes far bigger and further away than its southern border.

The Defence Secretary, Sir Michael Fallon, used the BBC's Andrew Marr programme to highlight the fact that London was closer to Pyongyang than to Los Angeles.

"This involves us," he said, which is true - but perhaps more in a diplomatic sense than as a target.

When I put his comments to South Korean journalist Jungeun Kim, she was taken aback. "Does he understand what he's talking about? I can't remember a time when Kim Jong-un has threatened the UK. His argument is with America." Of that, there is no doubt.

In Itaewon, I asked a uniformed US solder, one of more than 20,000 stationed on the Korean peninsula, what he thought of the current threat. Did he feel safe? "Yes I do, I've even brought my family here."

When I pushed him on US President Donald Trump's response to the crisis, his answer was brief, but damning. "He's dealt with it like a chump."

It's not hard to find others who agree. But any disdain felt towards the president is of course as nothing compared with the reputation of his North Korean counterpart.

And most here believe it will be the actions of the latter that will determine how this unedifying stand-off ultimately plays out.