Viewpoint: Why Trump's threats to Pakistan raise serious questions

EPA & Reuters

EPA & ReutersOn Monday night, President Donald Trump unveiled the long awaited results of his policy review of the Afghanistan war.

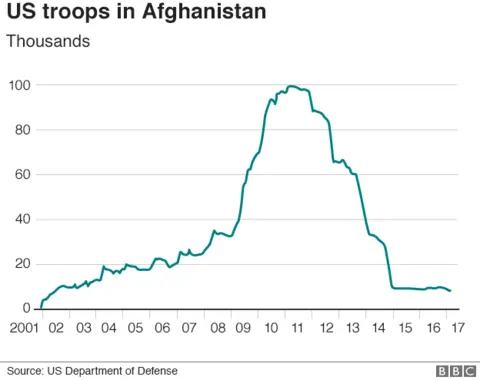

He announced that US troops would remain in the country without a timetable for withdrawal, with other reports suggesting that 4,000 further troops would be added. This would boost present numbers by around a third, although it would leave the American presence far short of its peak of 100,000 in 2010-11.

But Mr Trump's speech also included two important new elements. He launched a blistering attack on Pakistan, publicly articulating what his predecessors only said in private.

"We have been paying Pakistan billions and billions of dollars at the same time they are housing the very terrorists that we are fighting," declared the president. "It is time for Pakistan to demonstrate its commitment to civilisation, order, and to peace".

This was followed by more threats from Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and the National Security Council spokesman. And if this were not bad enough for Pakistan, Mr Trump then applauded India's "important contributions to stability in Afghanistan", urging New Delhi to play a larger role.

Since the beginning of the war, Pakistan has allowed the use of its territory to supply international troops in landlocked Afghanistan, tacitly accepted American drones over its airspace, and co-operated with Western intelligence agencies against some terrorist groups like Al Qaeda.

However, Pakistan's intelligence agency, the ISI, has also given shelter and support to Afghan insurgents from the 1970s to the present, including the especially virulent Haqqani network. Its aim has been to limit India's influence - but is also influenced by its disagreements with Kabul.

Ever since partition, Afghan governments of all stripes have rejected the border known as the Durand Line, laying claim to some Pashtun areas inside Pakistan.

There are three big questions around Trump's approach to Pakistan.

The first is whether his words will translate into action. After all, we've been here before. "We need to make clear to people that the cancer is in Pakistan", President Barack Obama told advisers in 2009, sending his CIA chief and national security adviser to Islamabad to deliver the message.

"You can't keep snakes in your backyard and expect them only to bite your neighbours", warned then Secretary of State Hilary Clinton in 2011. The same year, America's top military officer publicly declared that the Haqqani network was "a veritable arm" of Pakistani intelligence.

However, these warnings did not translate into action. Pakistan continued to receive around $1bn per year in so-called Coalition Support Funds, as well as other hundreds of millions of dollars in aid.

The Trump administration has threatened a range of punishments, including sanctions on Pakistani officials. But will they follow through? This is what Pakistani officials will hope to establish in the coming weeks.

AFP

AFPThe second question is how Pakistan will respond. In past crises, Pakistan has blocked Nato supply routes into Afghanistan, such as the Khyber Pass. There are alternative routes via Iran and Russia-dominated Central Asia, but the Trump administration's relations with Tehran and Moscow are even worse.

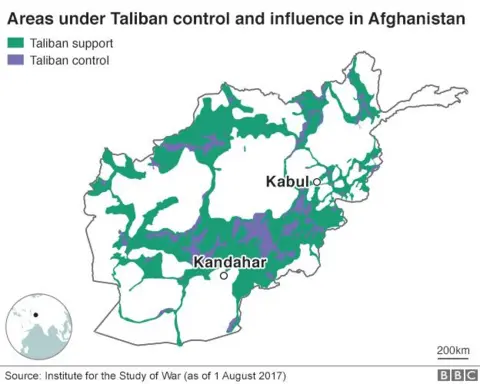

Beyond this, Pakistan could also shoot American drones out of the sky, ramp up its support for the Taliban, or halt intelligence co-operation entirely. Of course, Pakistan would have to consider the consequences, from losing out on IMF bailouts to provoking open US air strikes.

Increasingly confident

The third question is whether Pakistan can be coerced into abandoning a policy that has taken shape over 40 years.

Both Mr Trump and Mr Tillerson declared their openness to peace talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban. Pakistan's concern is that if such talks result in its Taliban allies sharing power in Afghanistan, this would reduce the Taliban's dependence on Pakistan.

Taliban leaders who have explored peace talks independently of their Pakistani patrons have ended up arrested or dead. It is possible that Pakistan will decide that it's worth maintaining influence over the Taliban, whatever the cost.

Domestically, Pakistan has continued supporting militants despite the death of 20,000 civilians in terrorist attacks over the past 15 years.

It's also notable that a meeting of Pakistani military and political leaders on Thursday concluded that the foreign minister should immediately set off on a tour of "friendly states", beginning with China.

Pakistan is increasingly confident in the support of Beijing, which is investing tens of billions of dollars in the country as part of the ambitious China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). However, it's not entirely clear how far China is willing to go to bail out Pakistan, financially or politically.

AFP

AFPFinally, what should we make of Trump's effort to enlist Indian support? Some critics have argued that this is likely to provoke Pakistan into expanding its support for the Taliban.

However, we should bear in mind that the US tried to restrict India's role in Afghanistan through the 2000s, with no positive change in Pakistan's behaviour. Instead, Pakistan is believed to have sponsored the bombing of the Indian embassy in Kabul in 2008, though Islamabad denies this.

India expanded its security role in Afghanistan from 2011 onwards, when it signed a strategic partnership with Kabul. It expanded its training of Afghan military officers, 4,000 so far, and gave second-hand attack helicopters to the struggling Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). This, too, had no apparent impact on Pakistan's policy.

We should be realistic about India's potential role. Delhi does not have the capacity to do too much more. It requires co-operation with its old partners Russia or Iran to send military supplies, but both those countries have expanded their own ties with parts of the Taliban in recent years.

We should also note that President Trump emphasised India's role in the specific areas of "economic assistance and development".

This assistance, to the tune of $2bn (£1.56bn), has contributed to India's popularity amongst Afghans. Delhi would not want military support to put that soft power at risk.

But on balance, as Western countries focus on terrorist threats from the Middle East and North Africa, and grow more weary of the longest war in their modern history, India's support to a weak Afghan state and its army should probably be welcomed.

Update 25 August 2017: The text referring to the bombing of the Indian embassy in Kabul in 2008 has been updated to include Islamabad's denial of involvement.