Cambodia leader tells critics to pay up, or pack up

Nicolas Axelrod/Getty Images

Nicolas Axelrod/Getty ImagesIn February this year, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen said that both he and US President Donald Trump shared a view of the media as "anarchic" troublemakers.

Two days earlier, a government spokesman had referenced Mr Trump's treatment of journalists in a Facebook post that threatened to shutter media outlets jeopardising "stability".

Now, the Cambodia Daily - an independent, English-language newspaper that has long been a thorn in the side of the government - is facing possible closure after being hit on 5 August with a $6.3m (£4.9m) bill for back taxes that authorities said had to be paid within 30 days.

On Tuesday, Mr Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge commander in power for more than thirty years, stepped up the pressure. If the sum was not paid, "please pack up your things and leave", he said, reportedly calling the publishers "thieves".

The move against the newspaper - which many believe is politically-motivated ahead of elections next year - is worrying Cambodia's journalists, who have long enjoyed far greater reporting freedom than their colleagues in neighbouring countries.

It comes as the government announces tax or regulatory probes into other perceived critics. Staff from the National Democratic Institute (NDI), a prominent US-funded non-profit group that played a key role in investigating alleged irregularities in the 2013 national elections, were on Wednesday ordered to leave the country under the aegis of a controversial NGO law passed in 2015.

The government said the NDI, which ruling party figures have accused in the past of being part of US-sponsored regime change efforts, had failed to acquire formal registration or pay taxes. The group told the Associated Press it had obeyed registration laws and worked with transparency for 25 years.

Aside from the Cambodia Daily, other independent media outlets - including the US government-funded Radio Free Asia and Voice of America - have also reportedly been accused of not complying with tax obligations.

These outlets, and the Phnom Penh Post, a newspaper which so far has not faced similar accusations, frequently report on topics that embarrass the government, from illegal logging to corruption and human rights abuses.

Siv Channa

Siv ChannaOn Wednesday the US State Department said it was "deeply concerned by the deterioration in Cambodia's democratic climate". Spokeswoman Heather Nauert denied that Mr Trump's rhetoric about the media was undermining the government's message, saying "we care about freedom of the press".

Lee Morgenbesser, an expert on authoritarian regimes at Australia's Griffith University, said that using back taxes as a pretext to "silence perceived opponents" was a "subtle technique" also used in Hungary, Russia, Turkey and Venezuela.

The Cambodian government denies the cases are political and points to the considerable freedom critical journalists have in the country, which it says is a democracy.

Ou Virak, a Cambodian analyst who heads the Future Forum think tank, said he believed that while the Daily's alleged tax issue gave the government a "convenient excuse" to target them, it would likely do so regardless as part of a broader stifling of critical voices.

He said that the US's diminishing voice on human rights and democratic freedoms combined with China's largesse and influence in Cambodia had emboldened the ruling Cambodian People's Party (CPP) to take action.

"Basically what you are now seeing is the end of a western-dominated era in Cambodian nation building and politics," he said, adding that previously, if activists "drummed up enough noise to get attention internationally" the aid-reliant government would back down.

A spokesman for the CPP said the party had "no motivation or any kind of reason" to be involved in what he characterised as strictly a matter between the Cambodia Daily and the tax department.

There was plenty of media aligned with the opposition party, Sous Yara said, adding that the Daily was trying to "politicise" the issue.

Deborah Krisher-Steele, the newspaper's deputy publisher, said tax authorities were not following regulations and had ignored a request for a meeting. She wants a full audit to be carried out, but insists that if any taxes are owed, "it could not be anywhere close" to the multi-million dollar sum demanded.

She has said the process is meant to "intimidate and harass the Cambodia Daily…and others who speak the truth".

The newspaper was set up in 1993 by her father, Bernard Krisher, a former Newsweek correspondent in Japan who was friendly with then-King Norodom Sihanouk.

Ms Krisher-Steele told the BBC the paper had been "losing money for many years" and was subsidised by Mr Krisher. She said she had been trying to run it as a profit-making business since April.

Reflecting the reality of Cambodian politics - where the prime minister himself often personally intervenes in policy issues or other disputes, announcing major decisions in long, meandering speeches - Mr Krisher has appealed directly to Hun Sen for help.

"Only you, Your Excellency, can stop the tax department from taking these measures," he wrote in a letter seen by the BBC. "I implore you to intervene to stop the shutting down of The Cambodia Daily."

AFP

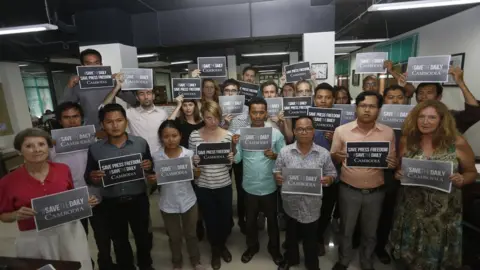

AFPThe newspaper's staff of local journalists and foreigners - and an alumni network of reporters who now work for media outlets around the world - are devastated by the prospect that it could close.

Robin McDowell, a journalist who helped found the Daily in 1993 and who went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 2016 with the Associated Press, said that getting the newspaper off the ground in that era, after UN-run elections, was a herculean endeavour.

Frequent blackouts meant the whole newspaper might be lost hours before being brought to the printer. "We were working 20 hours a day. Literally breathing and sleeping at the Daily," she said.

With few local journalists to recruit, motorcycle taxi drivers, pagoda boys and former policemen were all among those brought on board and trained as reporters.

It was a tiring and trying task, she said, but after years of war, the newspaper, along with the then fortnightly Phnom Penh Post, "gave Cambodians the first real look at the outside world and what a free press could look like".