Guam: A conflicted island at the centre of a firestorm

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesLast week a threat from North Korea to fire missiles into the sea near Guam led to a spike in war rhetoric from both the US and the North, and put the tiny island territory squarely at the centre of the world's attention. The BBC's Rupert Wingfield-Hayes went there to find out why Guam has been caught in the crosshairs.

Sitting here on Guam I am in the United States, and yet I am much closer to Manila than Los Angeles.

The nearest bit of the US proper, Hawaii, is nearly 4,000 miles (6,400km) to the east. Honolulu sits across the international dateline - so it is still Wednesday there - even though over here the sun is setting on Thursday.

Little wonder people in Guam often feel forgotten by the rest of America.

Standing in the immigration line it doesn't feel much like America either. The airport is filled with young families flooding off planes from Tokyo and Osaka, Seoul and Busan.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOf the 1.5 million tourists who flock to Guam's beaches each year, most are from Japan and South Korea. For them, it's a little bit of America anchored off the coast of Asia.

The car rental shops do a brisk trade in bright yellow Mustang convertibles. Young South Korean couples cruise the beach roads, the hood down.

There are shooting ranges that do an equally brisk trade with Japanese men eager to have a go with an M16, something that is illegal and taboo back home in Tokyo.

The fact that Guam belongs to America is an accident of history, a bit of war booty left over from the 1898 Spanish-American war. It's the same deal that gave the US Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

And that has left a difficult legacy.

The Philippines eventually got independence, but Guam remains a US territory - in effect a self-governing colony.

Guamanians - as the locals refer to themselves - are US citizens. But here at home they have no right to vote in US presidential elections, and even though they elect a member of the US Congress, she cannot vote on any legislation.

Everyone I've spoken to here agrees this situation is untenable, that Guam either needs to become a fully-fledged US state, or an independent country. But don't count on the latter.

The native people of Guam are called Chamorro. Their ancestors came here 4,000 years ago. Like their distant cousins in Hawaii and Samoa they are deeply conflicted about their American identity.

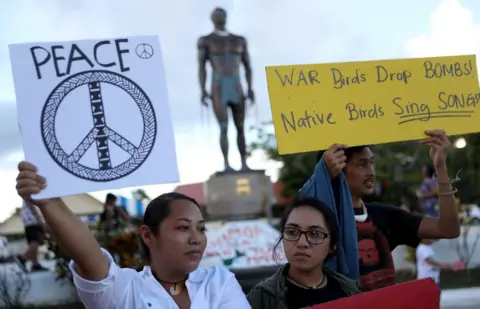

One evening this week a group of pro-independence Chamorro campaigners gathered on a street corner in the main town Hagatna. They held up peace banners and Guam flags and sang traditional folk songs. Passing cars hooted their support.

"We've been used for other people's war's for too long," one young woman told me. "Its time for us to stop being a colony."

"The American military occupies 27% of the land here," the leader of the protest Kenneth tells me.

"A lot of that land was taken from Chamorro families after World War Two. Not all of us accept this. We are an indigenous people. We've been here for thousands of years. We've been stuck in the middle before and we don't want history to repeat itself."

But that huge US military presence has affected the identity of Guam in surprising ways.

Virtually every family I've spoken to has a connection to the military, an uncle or brother or cousin who has served. Per capital this little island sends more of its sons and daughters to the US military than any other place in the United States.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPartly that's a product of poverty. Guam is poorer than Mississippi. But it means Guam is surprisingly patriotic.

Over and over during the last week I've been told: "I feel safe because the US military is here, they are powerful and they will protect us. North Korea will not do anything to us, and if they do we will destroy them."

But it's also the reason Kim Jong-un is so interested in this tiny scrap of American land. It's not about Guam's proximity to Asia, it's what America keeps here.

On the north end of the island, a huge airbase is hidden behind dense jungle. Beside its runways a fleet of sleek B1 bombers stands ready to strike back at North Korea should it ever attack the South.

On the west coast of Guam an even more secret base is home to a squadron of nuclear attack submarines.

But perhaps even more important than those is what's hidden under the hills in the south of the island.

"This is the US military's store house," Governor Eddie Calvo told me.

Governor Calvo is a big, ebullient politician. He's a republican and a fan of US President Donald Trump.

"He called me on Saturday when I was gardening," the governor tells me. "The President told me he is behind us 1,000%," he says laughing.

Governor Calvo is acutely aware of the strategic importance of his little island to United States.

"There are more munitions stored here on Guam than any other place in the United States," he tells me.

Munitions are the real key to prosecuting a war, and they get used up really quickly once conflict breaks out. Here under the hills of Guam the US stores enough bombs and missiles to keep a war going for weeks and weeks.

It is what makes Guam so important to the United States, and what now makes this little island, with its long sandy beaches and ridiculously friendly people, a target for North Korea's ballistic missiles.