Can North Korea nuclear threat focus minds?

Reuters

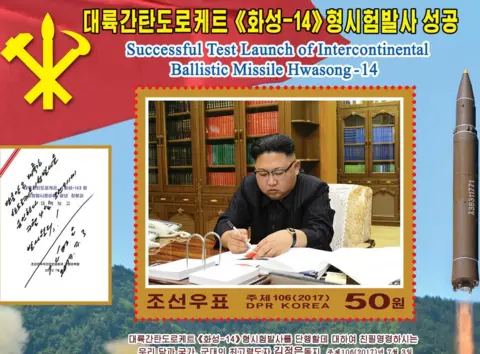

ReutersThe crisis surrounding North Korea's nuclear weapons and missile programmes has reached a new and more dangerous phase.

For decades efforts have continued to try to persuade or pressure Pyongyang to give up its weapons programme.

A fully-fledged nuclear capability - warheads that could actually be delivered to a distant target at the tip of a long-range missile - seemed years away. But no longer.

It is impossible to assess the exact capability that North Korea now has. It claims to have missiles that can reach the continental United States - and two recent tests convince Western experts that this may well be a possibility.

The Japanese government, in its latest defence white paper, suggests that Pyongyang may already have the capacity to miniaturise a nuclear warhead to be placed on such a long-range missile.

US officials, too, believe that North Korea has manufactured small nuclear warheads suitable for a long range missile, but it is not clear - despite claims from Pyongyang - that these have been tested.

A working long-range nuclear capability for North Korea is not now a question of "if", but "when". And that "when" could be within the next few years.

Glimmer of a chance

That this time-scale coincides with President Donald Trump's tenure in the White House is an accident of history.

But while it gives the North Korean nuclear crisis an added danger, it also, perversely may offer a glimmer of a chance for progress.

The cacophony of foreign policy bluster, bravado and inexperience that makes up the US president's Twitter feed gives many cause for concern. The North Korean leader is seen in the West as unpredictable and very much a loose cannon. Well now, up to a point, the US has a loose cannon of its own.

EPA

EPAMr Trump, to paraphrase a former US defence secretary is a "known unknown". Nobody knows how he might react. And that makes things more dangerous but it also seems to be concentrating minds, not least in Beijing.

Of course, as in so many areas, we don't really know what US policy actually is. In complex diplomacy the clarity of messaging is important. So who actually represents US foreign policy?

Is it Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who under the right circumstances seems to be holding out the possibility of talks with Pyongyang? (Even Mr Trump himself has envisioned such a possibility).

Or is it the Oval Office's tweet-meister, who seems to be ramping up the pressure on Pyongyang?

There is no doubt that a fork in the road has been reached. North Korea's progress means that it will soon be able to threaten the US with a nuclear strike.

Reuters

ReutersThis is a game-changer and the policy options facing the Trump administration, the Chinese, the South Koreans and Japan are all difficult and unpalatable to varying degrees.

One option would be to confront the North Korean regime by every means possible. So stepped-up sanctions; a regional military build-up; and a willingness to go to war if necessary - ultimately, in other words, to seek a change of regime in Pyongyang.

That promises Armageddon on the Korean Peninsula and is not going to appeal to China, the pivotal diplomatic player in this drama.

Another option is containment.

It is kind of where we are heading right now. Stronger international sanctions - last weekend's UN Security Council decision represents almost a trade embargo against North Korea in a small number of sectors crucial to its foreign revenue earnings; the provision of defensive weapons - like the Thaad anti-missile system deployed in South Korea - to America's allies.

But containment is no solution in itself and it risks changing into confrontation as each new crisis develops.

Then of course there is diplomacy. This remains, for now, a tall order.

But a combination of factors - North Korea's technical progress, the uncertainties prompted by the Trump administration's arrival in office and the fact that the world does now stand at crossroads on North Korea suggests that a diplomatic moment may just be possible.

What are the new sanctions?

AFP

AFP- Importing coal, seafood, iron and iron ore, lead and lead ore from North Korea is banned

- Countries cannot receive new North Korean workers

- No new joint ventures with North Korean entities or individuals

- No new investment in existing joint ventures

- More individuals targeted with travel bans and assets freezes

- Member states to report to the UN Security Council within 90 days on how they have implemented resolution

An essential precursor was the tougher sanctions regime, passed by the Security Council, endorsed by both China and Russia together with the explicit calls from Beijing for Pyongyang to halt nuclear and missile tests. North Korea's foreign minister was engaging with other countries at the recent Manila meetings even though his message was as hard-line as ever.

Now - despite the rising rhetoric - there needs to be a stock-taking. Where will this crisis go? Can a space be created for some kind of diplomatic opening?

Waiting for a signal

Diplomacy may not have worked in the past but it has certainly been tried. Remember the Kedo experiment back in the 1990s? This was the so-called Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization which was established after an agreement in 1994.

It was intended to provide two nuclear reactors to North Korea of a type less amenable to the diversion of nuclear materials for bomb-making. In return North Korea was to close down much of its existing nuclear industry.

There was a plan for improved relations between Washington and Pyongyang and so on. Key North Korean facilities were opened up to IAEA inspection.

But Kedo collapsed in 2002 amidst US fears that Pyongyang had a clandestine uranium enrichment programme and the international inspectors were expelled.

Kedo, though, had a clear purpose - to roll back and shutter those North Korean nuclear facilities implicated in its military programme. But that was more than 20 years ago. Rolling back North Korea's nuclear weapons and missile programme is no longer a realistic option.

What would the goals of a new diplomatic deal be? Is Trump's America willing to live in the shadow of a North Korean nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile? And would Kim's North Korea really want to open up or liberalise in any way that might call into question the future of the regime?

We now wait for a signal from Pyongyang. A temporary halt to testing could mean something of a pause for thought. But if missile testing is renewed then we will be on the launch-pad to a whole new phase in this potentially catastrophic drama.