North Korea new missile test: A game-changer?

North Korea's confident announcement that it has successfully launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of striking the US is another iteration in the high stakes game of international poker that Pyongyang appears to excel at.

Carefully timed to coincide with the 4 July holidays in the US, Kim Jong-un's triumphal blast has simultaneously allowed the North Korean authoritarian leader to make good on his promises of military modernisation to his own people while exposing the hollow overconfident tweets of President Donald Trump that an ICBM launch "won't happen".

The launch of the North's Hwasong-14 rocket is in practical terms merely an incremental step forward from an earlier launch in May, when a similar rocket flew for 30 minutes, to a height of some 1,312 miles (2,111km) over a distance of some 489 miles.

The most recent missile added seven to nine minutes of flight time, an extra 400 miles or so in height and a further 88 miles in overall distance.

KCNA/via REUTERS

KCNA/via REUTERSSuperficially this is simply more of the same pattern of provocation and tactical sabre-rattling that the North has been pursuing for decades, whether through its longstanding quest to acquire nuclear weapons (dating from the 1960s) or its missile testing programme, sharply accelerated in the course of last year.

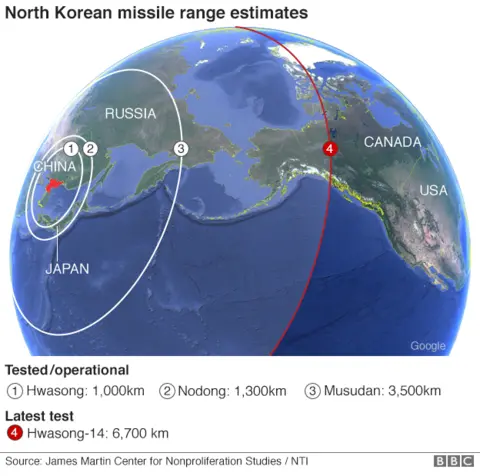

Yet, by bringing Alaska within range, the new test is an unambiguous game-changer in both symbolical and practical terms.

US territory (albeit separate from the contiguous continental US) is now finally within Pyongyang's cross-hairs and for the first time a US president has to accept that the North poses a "real and present" danger not merely to north-east Asia and America's key allies - but to the US proper.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesPresident Trump's weakness lies in having overplayed his hand too publicly and too loudly.

His initial gambit of deploying a US "armada" to the region in the form of the USS Carl Vinson battle group, not only involved a poor use of historical analogies (the ill-fated 16th Century Spanish fleet was probably the least auspicious of reference points), but also signally failed to intimidate the North Koreans.

Similarly, openly pressuring the Chinese to impose punitive sanctions on North Korea in return for economic restraint from the US through a Trumpian concession not to list Beijing as a currency manipulator also appears to have failed.

President Xi, notwithstanding the positive mood music of the April Mar-a-Lago summit, appears to have avoided being boxed in by Trump, and China's reaction to the North's latest provocation is likely to be limited to a familiar pattern of rhetorical condemnation and a call for calm from all parties.

Washington's immediate options are limited.

Military action - notwithstanding the hawkish recommendations of Republican senators such as John McCain and Lindsay Graham - is next to impossible given the risks involved to Seoul and the poor prospects of success, either in terms of removing the North's strategic assets or its political leadership.

Sanctions are likely to be revisited, through a reconvening of the UN Security Council, but the political process is slow and enforcement is at best a partial and therefore ineffectual approach.

Reuters

ReutersTalks are one way forward and the convergence of views between Washington and Seoul on the back of President Moon's recent visit to the US suggest that some sort of partial re-engagement with the North might be on the cards, albeit within a framework of reinforced deterrence.

Yet, for now the momentum is all with Pyongyang, which has little incentive to sit down with the US and can afford to play for time in accelerating its military modernisation efforts while capitalising on divisions within the international community.

While the US, South Korean and Japanese leaders will be united in pushing for tough measures at this week's G20 summit in Germany, they will be hard pressed to secure the support of either China or Russia for anything beyond a bland, condemnatory declaration.

The dangers of the present crisis are two-fold.

A more confident Kim Jong-un, emboldened by his latest success may become less risk-averse, engaging in conventional military brinkmanship which, while not going as far as pre-emptive attacks on his neighbours, might spill over into conflict through miscalculation rather than through design.

Alternatively, the US confronted by the unpalatable reality of seeing the North cross yet another supposedly non-negotiable "red line" may simply choose to avert its eyes.

For a president wedded to his own version of "fake news", the easiest way to cope with an inconvenient truth may be to redefine or simply ignore the original "red line".

This would be a major mistake since it will do nothing to deter the North while encouraging other states in the region to pursue their own military modernisation plans, storing up even greater problems for the future.

Ultimately, Mr Trump, if he wishes to demonstrate that he is indeed master of the "art of the deal", will need to give up the bully pulpit of megaphone diplomacy via twitter and pivot towards a more enlightened approach.

This could involve the imaginative despatch of a high-profile US senior statesman to negotiate with and appeal to the ego and amour propre of the young North Korean leader.

It could also involve closer co-ordination with America's allies, most notably South Korea, in offering some high-profile political concessions to the North - whether the establishment of a US liaison mission in Pyongyang or a sequenced pattern of asymmetric conventional force reductions on the peninsula.

Right now, Washington (for the sake of the region and the wider world) urgently needs a long-term, sustained and calibrated strategy for dealing with the North that is more than a reactive game of eye-ball to eye-ball posturing.

An impulsive, attention deficient and hyper-active President Trump would be better advised to switch from playing poker to chess.

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is a Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia, Asia Programme, Chatham House and Senior Lecturer in Japanese Politics and the International Relations of East Asia, University of Cambridge