Philippines conflict: Starving residents tell of terror in Marawi

For the past two weeks the Philippines army has been fighting Islamist militants in the southern city of Marawi. So far, the conflict has killed at least 170 people, including 20 civilians, and more than 180,000 residents have fled. The BBC's South East Asia correspondent Jonathan Head reports from Marawi.

For more than a week the military spokesmen have been offering the same, upbeat outlook in the embattled city of Marawi. The Philippines armed forces controls nearly all of the city, they have been saying; the black-clad militants, who so surprised them by seizing Marawi in the name of so-called Islamic State on 23 May, have taken heavy casualties, and are encircled.

The military will, of course, eventually retake the city. Even fighters happy to die for Islam cannot withstand constant bombardment indefinitely.

But nearly all of the city is still off-limits to non-military personnel.

The large, provincial government offices compound on the city outskirts is the only completely secure place in Marawi, and it has become a crowded, noisy operation centre for what is turning into a large-scale humanitarian effort.

Behind all the good will and sense of purpose, you cannot escape the impression that the Philippines is confronting a national crisis in Marawi, one few of its leaders saw coming.

Five hundred metres down the road towards the commercial centre of Marawi, an armed police officer waves you down and tells you to go no further. His colleagues seem relaxed enough, cooking rice and dozing in the sun.

But intermittent crackles of gunfire, quite close, show the fighting is not far away.

An uneasy silence

In the middle of the crossroads an orange concrete bollard proudly announces that you are about to enter the only truly Islamic city in the Philippines, the cultural heart of the Moro people.

There is no-one there now; just stray cats and dogs, and trucks full of grim-faced troops racing to and from the front line. The buildings have been pitted by bullets.

The uneasy silence is broken by the buzz of helicopters, and we watched as they zipped towards the city centre. Seconds later two loud detonations are followed by white plumes of smoke over the palm trees, as their rockets strike.

Saturday was a good day for the officials and volunteers at the provincial hall. They had been getting increasingly desperate phone calls from people trapped inside areas of Marawi held by the militants. At last some of them had managed to break out.

They arrived in three trucks, a mix of Christians and Muslims, young and old, their faces wearing the shock, exhaustion and hunger of their ordeal.

The Christians, in particular, had lived in terror of what the fanatical Islamists would do if they had found them; non-Muslims have routinely been murdered.

Stories of escape

Their stories were hair-raising. I had watched Anparo Lasola walk into the hall, looking dazed and clutching the youngest of her six children.

Smiling volunteers handed them bottles of water and biscuits, but the children were in the early stages of malnutrition after eleven days with nothing to eat but a small bowl of rice each day.

Anparo described how they hid with 70 other Christians in a basement, and how stressed everyone became when the children cried, for fear they would be given away to the gunmen outside.

Another mother, a Muslim, said she had to dissuade the militants from taking her 14-year-old son to fight.

Anparo was saved by Norodin Alonto Lucman, a renowned community leader of the local Maranao clan, who would have been allowed to leave at any time.

He chose to hide the 71 Christians in his home, using his authority with the young militants, many of them also Maranaos, to stop them searching the house.

Then he led the Christians to safety, at the end racing across a bridge through a gun battle between the two forces. He described meeting one 28-year-old fighter who was a family friend, and asking him to put down his gun and his black uniform, offering to arrange safe passage with the government side.

The man had refused. This is jihad - we want to die, he told him.

Norodin and other Maranao leaders worry about how many more civilians will die, and how much damage will be done to their city before the militants are driven out.

Hundreds, not dozens

But for now their concern is not one of the military's priorities. Rowan Rimas is a major in the marines, who has been deployed to help the hard-pressed army. He described the unfamiliar urban warfare his men were engaged in as akin to the Battle of Mogadishu.

How would they deal with young militants prepared to fight to the death, I asked?

If that's what they want, we will help them to reach heaven, he said.

Estimates of how many of the Islamic fighters remain in Marawi have varied wildly. But the government now acknowledges that it is confronted by a militant force many hundreds strong, not the few dozen it first believed were there.

The tense checkpoints on roads leading out of Marawi, where ID cards are laboriously matched against the grainy portraits on the latest wanted posters, tell of another fear; that the militants will break out, and attack somewhere else.

IS allegiance

Norodin told me many of the fighters he encountered on his doorstep were not locals; they were ethic Tausug and Yakan, he said, from the Sulu archipelago in the far south-west of the country, a stronghold of another ruthless jihadist group, Abu Sayyaf.

This is clear evidence of the alliance believed to have been formed last year between four hard-line Islamist groups on Mindanao, all pledging allegiance to so-called Islamic State.

The acknowledged leader, or amir, of this alliance is Isnilon Hapilon, the Abu Sayyaf commander the military was trying to capture when it inadvertently interrupted the militants' occupation of Marawi last month.

But the driving force behind this alliance is the two Maute brothers, both well-educated in the Middle East, and from a prestigious Maranao family.

Like Norodin Alonto Lucman, Omar Solitario is from an older generation of Moro fighters, who waged a more conventional insurgency against the government in the 1970s and 80s, and then became political and business leaders in the ceasefires that have lasted for most of the past two decades.

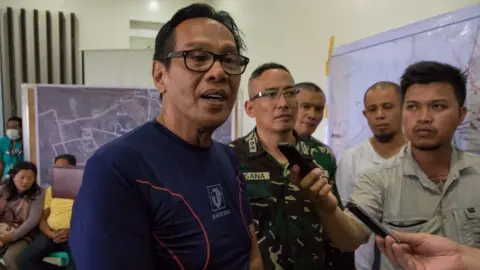

He is a former mayor of Marawi, and, like Norodin, has family ties to the Mautes. President Duterte has asked him several times to try to mediate, but the young militants, he says, are not interested.

Mr Solitario described seeing the children of his friends being drawn to the extremist groups, who demanded that their parents help fund the militants to show their devotion to Islam.

"Their capability to hoodwink youngsters - it's like a magician," he said.

"They are trying to infiltrate the best schools. This is a virus - you cannot stop this with guns alone."

A generational gap

Both men are urging President Duterte to accelerate the agreement on Moro autonomy signed by his predecessor, to give the older Moro leaders something to show for their struggle.

But those leaders are accused of growing soft and corrupt in the long years of peace. Frustrated young Muslims are looking for something different.

In some ways the crisis of leadership among the Moros mirrors that in the rest of the country. Last year millions of Filipinos, weary of a corrupt and self-seeking political elite, elected a maverick, blunt-speaking mayor from Mindanao as president.

Now Rodrigo Duterte must try to make good on his promise, to find a lasting solution to the violence that has wracked his home-island for so long.