What African architecture can teach the world

Danko Stjepanovic

Danko StjepanovicSalt bricks and sweeping mud walls - as recently showcased by some African architects - may be the building blocks for innovative designs of the future.

Such ideas were explored by Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo in a major exhibition she recently curated in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

She wanted to look at how regions such as Africa are able to function with scarce resources.

"I think ultimately the big elephant in the room for most of us is climate change," Ms Oshinowo told the BBC about the show The Beauty of Impermanence: An Architecture of Adaptability.

Designers from 26 countries were invited to Sharjah to come up with works to address the issue of scarcity.

For Ethiopian designer Miriam Hillawi Abraham, this meant building what looked like a church out of salt.

She called the work Museum of Artifice - and it was a nod to Ethiopia's famous rock-hewn churches in Lalibela as well as the remote northern village of Dallol.

This is in the Danakil Depression, more than 330ft (100m) below sea level, and arguably the hottest place on Earth.

Danko Stjepanovic

Danko StjepanovicLargely abandoned now, Dallol still has single-storey buildings made out of blocks cut from the nearby salt lakes.

Ms Miriam's structure, made from pink Himalayan salt, will erode without regular maintenance.

"It does raise the question: 'What can we learn from these locations?'" Ms Oshinowo said.

Another work at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial was by Hive Earth Studio, a Ghanaian architecture firm that specialises in compressing locally sourced earth to form walls.

It was called Eta'dan, meaning "mud wall" in Ghana's Fante language - and the soil was sourced in the UAE to reduce the environmental impact of transporting materials.

Danko Stjepanovic

Danko StjepanovicHive Earth's ethos is to learn from the past to create buildings for the present, seeking sustainability and a pleasing aesthetic.

Ms Oshinowo said the design team, who had been at the forefront of exploring the technology of rammed earth in West Africa, used rocks from the UAE to achieve the layering and strength required for the walls.

"Through material exploration they were able to transfer the skills of rammed earth," she said.

"There was a lot of testing to see how it would work in this environment, especially where you have a lot of sand.

"It just shows you what the possibilities are. If we think of things differently, we really can change the way we build and the way we design our buildings."

Danko Stjepanovic

Danko StjepanovicGhana-based design duo Dominique Petit-Frère and Emil Grip tackled the potential of unfinished building projects - prevalent in West Africa.

Known as Limbo Accra, the pair transformed a derelict shopping mall into an inviting space.

They worked in collaboration with Ivorian fashion label Super Yaya to artfully drape strips of white calico cotton fabric across the entrance.

The work, Super Limbo, was also a nod to Bedouin culture and their desert tents.

Danko Stjepanovic

Danko Stjepanovic"We were inspired to connect our experiences of navigating the remains of unfinished architecture in West Africa with a Middle Eastern setting," Ms Petit-Frère told the BBC.

Architects Papa Omotayo and Eve Nnaji, based in the Nigerian city of Lagos, took inspiration from the potted plants and bird cages they spotted being tended by mechanics in an industrial area of Sharjah.

Danko Stjepanovic

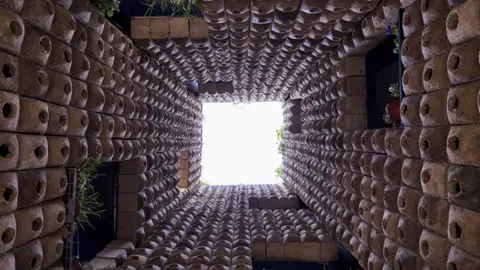

Danko StjepanovicTheir three-storey structure We Rest at the Birds Nest was made from scaffolding and organic waste, providing a sanctuary for both birds and workers.

Metal steps led up to platforms decorated with vegetation, while rows of 2,000 biodegradable cardboard nests lined an atrium that descended from the open rooftop to the ground. Passageway windows allowed a view into the birds' haven.

"As architects we tend to stay focused on people, but we share this planet," Ms Oshinowo said.

"When we start to think about accommodating other species, it's also a very powerful narrative."

Danko Stjepanovic

Danko StjepanovicMs Oshinowo hopes the exhibition gave those attending an opportunity to pause and reflect on sustainability and design.

And the exhibits from Africa, a continent disproportionately affected by the climate crisis, showed how designers were starting to work in "better balance with ecology".

Images subject to copyright.