The Nigerians who want Israel to accept them as Jews

Irums

IrumsRocking back and forth, Shlomo Ben Yaakov reads from a Torah scroll at a synagogue on the outskirts of Nigeria's capital, Abuja.

Intermittently his soft mellow voice rises in Hebrew and he is joined by the dozens who recite after him.

Most do not fully understand the language, but this small Nigerian community claims Jewish ancestry dating back hundreds of years - and they are left frustrated by a lack of recognition by Israel.

"I consider myself a Jew," says Mr Yaakov.

Outside the Gihon Hebrew Synagogue in the suburb of Jikwoyi a table is laid inside a tent built from palm leaves to celebrate Sukkot, a festival that commemorates the years Jews spent in the desert on their way to the Promised Land.

"Just as we are doing this now, they are doing same in Israel," says Mr Yaakov, as people share traditional cholla bread (baked at the synagogue) and wine from small cups being passed around.

He is an Igbo - one of Nigeria's three dominant ethnic groups which originates in the south-east of the country. His given Igbo name is Nnaemezuo Maduako.

Irums

IrumsMany Igbos believe they have Jewish heritage as one of the so-called 10 lost tribes of Israel, though most are not practising Jews like Mr Yaakov. They comprise less than 0.1% of the estimated 35 million Igbos.

These tribes were said to have disappeared after being taken into captivity when the northern Israelite kingdom was conquered in the 8th Century BC - and the Ethiopian Jewish community, for example, is recognised as one of them.

Igbo customs such as male circumcision, mourning the dead for seven days, celebrating the new moon and conducting wedding ceremonies under a canopy have reinforced this belief about their Jewish heritage.

'No proof'

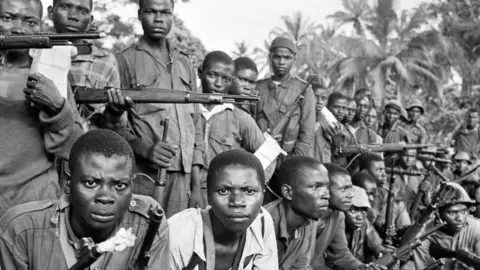

But Chidi Ugwu, an Igbo who is an anthropologist at the University of Nigeria in Enugu, says this identification with Judaism emerged only after the Biafran civil war.

The Igbos had been fighting for secession from Nigeria, but lost what was a brutal conflict between 1967-1970.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome people "were looking for some psychological boost to hang on to" so began to make the Jewish connection, he says.

They saw themselves as persecuted people, much as Jewish people have been through history, especially during the Holocaust.

"It is insulting to call the Igbos the lost tribe of anybody, there is no historical or archaeological evidence to back that up," he told the BBC.

He argues that as evidence suggests the Igbos were among those who migrated out of Egypt several thousand years ago, it may be that Jews picked up Igbo customs when they went there.

Irums

IrumsSeveral years ago controversial efforts were made to prove a genetic lineage, but a DNA test found no Jewish connection.

Rabbi Eliezer Simcha Weisz, chairman of the foreign affairs department of the Rabbinate Council of Israel - the body that determines claims of Jewish ancestry, is also in no doubt.

"They claim to be one of the descendants of Gad, one of the sons of our forefather Jacob - but they can't prove their grandparents were Jewish," he told the BBC.

"And the customs they speak of, you can find people all over the world who have Jewish practices."

He said unless the Nigerian Jews converted to Judaism - a process that entails various rituals and appearing before a Jewish court (which is unavailable in Nigeria) - they would not be recognised.

Mr Yaakov regards the idea of having to go through a conversion as an insult.

"As a convert we would be seen as second-class citizens," he says.

Secessionist surge

The congregants at Gihon take their beliefs seriously - and they and Nigeria's estimated 12,000-strong community of practising Jews - are supported by some other Orthodox Jewish groups around the world, which donate to them, make solidarity visits and campaign for their recognition.

One prominent supporter is Dani Limor, a former Mossad agent who once ran an operation to secretly take Ethiopian Jews to Israel via Sudan. He has been visiting the Jewish communities in Nigeria since the 1980s and argues that Jewish practice in the West African nation predates the civil war.

Irums

IrumsHe believes in a school of thought that says they came from Morocco 500 years ago, first settling in Timbuktu before travelling further south - and he hopes they will eventually get the recognition they deserve.

"Judaism goes beyond the colour of the skin, it is in the heart," he told the BBC.

Gihon synagogue, said to be the oldest in Nigeria, was founded in the 1980s by Ovadai Avichai and two others who had been raised as Christians.

The friends decided to turn to Judaism when they realised the Bible's Old Testament was the foundation of the Jewish religion.

He said it was like the Jew in him had been rekindled - and given the similarities between Jewish customs and Igbo traditions he was convinced that Judaism was the true path.

AFP

AFPAbuja's Gihon synagogue now has a mixture of different ethnic groups among the more than 40 families who attend.

In the last few years the number of those worshipping as Jews in southern Nigeria has increased sharply, says the BBC's Chiagozie Nwonwu, an expert on the region.

This is largely thanks to the Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob), a group which restarted the Igbo campaign for secession in 2014.

It is led by Nnamdi Kanu, who has reminded his followers of their alleged Jewish heritage and encouraged them to embrace the faith. The charismatic leader was once purportedly pictured praying at the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

But his followers are not regarded as authentic Jews by Nigeria's more established communities as some combine elements of Judaism and Christianity in their worship most associated with Messianic Judaism.

Mr Kanu is now in detention facing trial for treason and Ipob, which has recently taken up arms, has been banned as a terrorist group.

"The first time Ipob emerged, I cried at the synagogue. I said: 'This young boy has come to cause problems for us because what he's doing is unnecessary,'" says Mr Avichai, a Biafra war veteran.

He fears the activities of Ipob threaten the peaceful worship of the 70 or so apolitical Jewish communities.

This happened earlier this year when a Jewish community leader in the south-east was jailed for a month after her congregation received three visitors from Israel.

They had come to film the donation of a Torah scroll - often too expensive for local groups to purchase - but were suspected of having connections to Ipob and deported.

One worshipper at Gihon told me Mr Kanu had influenced his decision to join the synagogue - but the recent evolution of Ipob's campaign into an armed struggle went against the tenets of Judaism.

Mr Yaakov is not interested in the politics around being Jewish - for him it is the spiritual aspect that is important.

Official recognition by Israel of the fraction of Igbos like him as Jews would help the religious community become more organised in Nigeria. For example, at the moment there is no chief rabbi and finding kosher products can be a challenge. They are usually only sold in a few shops owned by Jewish expats - the community generally eats what is produced locally so they can follow Kosher rules.

Mr Yaakov would love to train to become the first Nigerian rabbi, something that can only be done by studying at a rabbinical school or under an experienced rabbi.

"For those of us who know our roots, we are confident of our identity," he says.

"If the Christians and Muslims can accept their own and support them, then I think the Jews should also show some encouragement."