Ethiopia's Tigray crisis: Tragedy of the man-made famine

AFP

AFP"There's famine now in Tigray." The world's most senior humanitarian official, UN emergency relief coordinator Mark Lowcock, said these frank words on the situation in the northern Ethiopian region on Thursday.

His statement - at a roundtable discussion ahead of the G7 summit - drew on the authoritative assessment of the crisis by the UN-backed Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC).

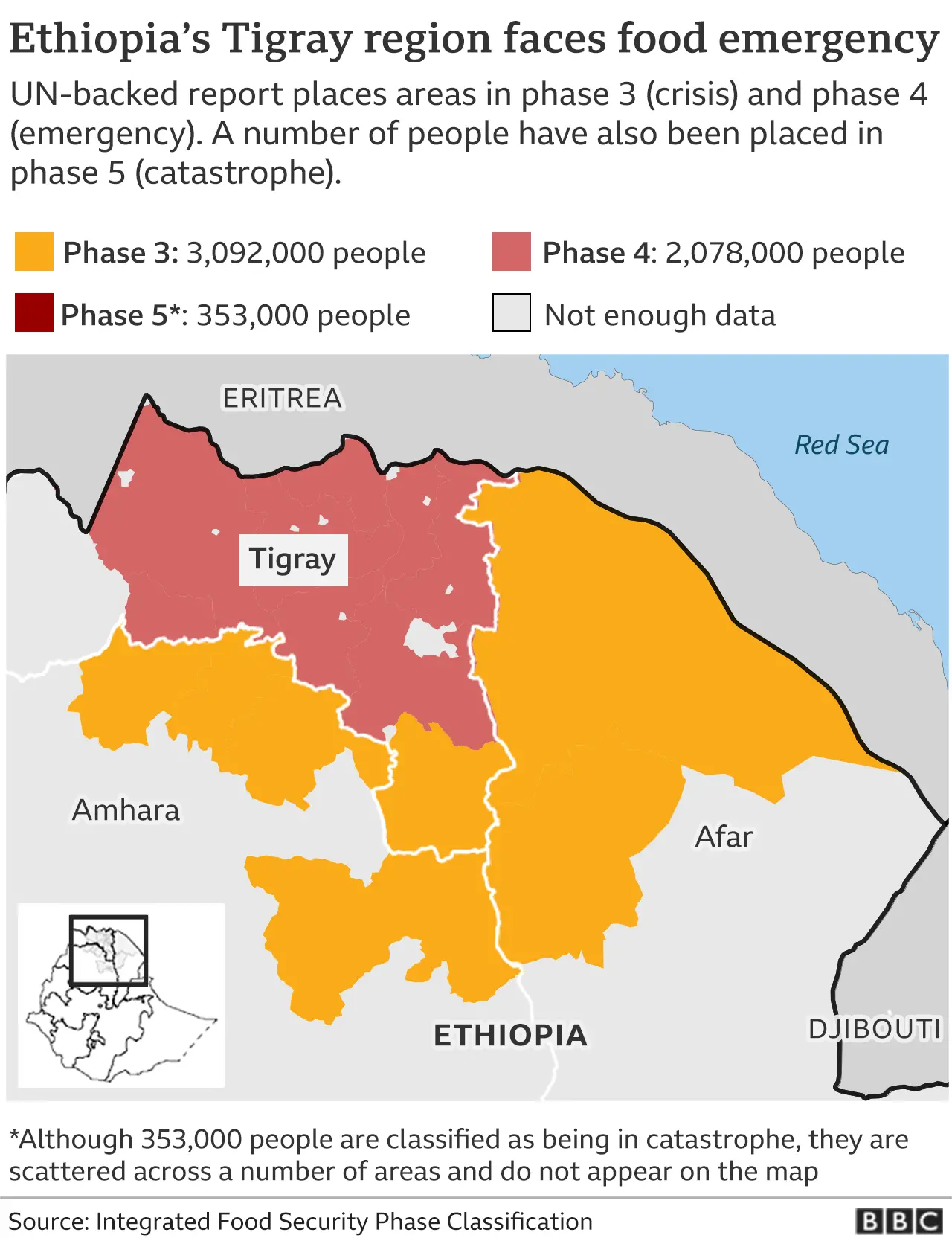

In a report, it estimated that 353,000 people in Tigray were in phase 5 (catastrophe) and a further 1.769 million are in phase 4 (emergency).

That's a technical way of saying "famine". The IPC didn't use that word because it's so politically sensitive - the Ethiopian government would object.

Behind these numbers lies a brutal human tragedy. Huge numbers of deaths by starvation are unavoidable. Indeed, it is already happening.

Tigrayans tell of remote villages where people are found dead in the morning, having perished overnight. Women who were kidnapped by soldiers and held as sexual slaves, cared for in hospitals or safe houses, are tormented by the children from whom they were separated, who may well be starving without their mothers' care.

AFP

AFPStarvation is a cruel way to die, as the undernourished body consumes its own organs in order to generate enough energy to keep a flicker of life.

Those who succumb first are young children - typically two-thirds of those who die in a famine. Based on the just-released numbers from Tigray, it is quite realistic to fear 300,000 child deaths - equivalent to half the pre-school children in London.

The numbers err on the side of understatement. The survey teams could not reach all areas and relied on extrapolating from limited data.

According to the Tigray Humanitarian Atlas published by researchers at Belgium's University of Ghent, out of Tigray's six million people:

- Just one-third live in areas controlled by the Ethiopian government

- Another third are in areas occupied by the Eritrean army, which is Ethiopia's military ally, but which doesn't cooperate with humanitarian agencies

- A further 1.5 million live in rural areas controlled by the Tigrayan rebels, where aid workers cannot go and mobile-phone coverage has been shut off.

The government says that there are only "remnants" of resistance by Tigrayan rebels and promises it will soon be in full control.

The UN forecasts that the situation will deteriorate - the question is just how far and how fast.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe IPC report includes the line that "this report has not been endorsed by the Government of Ethiopia".

That's a warning.

The Ethiopian authorities will probably dispute the "famine" warning, on the technicality that the "catastrophe" conditions were spread out across different parts of Tigray and in no single location did the proportion of people in phase five reach 20%, the standard threshold for declaring famine.

Ploughing in the darkness

At the roundtable, USAid administrator Samantha Power waved away what she called "attempts at obfuscation by the Ethiopian government".

Humanitarian workers are worried that, with the summer rains now falling across Tigray, farmers need to be busy cultivating - and they're not.

A team from the University of Ghent, until last year working on agricultural projects in the region, describes how large areas of farmland are abandoned this year because peasants don't have seeds, oxen to plough, or fertilizers.

Worse, soldiers threaten them: "You won't plough, you won't harvest, and if you try we will punish you."

In remoter villages, farmers rouse their oxen at midnight and plough in the darkness before dawn, with scouts to warn them of marauding soldiers.

If there's no harvest later this year, Tigrayans will depend on aid - or starve.

This is a man-made famine. There's no drought, and last year's locust swarms have gone.

The region was classified as borderline "food secure" seven months ago, before fighting erupted between the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) - then the party in power in the region - and the federal government, led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

Food aid stolen

The war disrupted services, closed banks and stopped the government's biggest emergency response system - the "productive safety net programme".

The most fertile parts of Tigray were occupied by forces from neighbouring Amhara region, depriving Tigrayans of their farms and also shutting down the biggest seasonal labour opportunities.

More on the Tigray crisis:

The Eritrean forces that joined the conflict have been accused of widespread pillage and, along with the Ethiopian army, of burning crops, destroying health facilities, and preventing farmers from ploughing their land.

The UN conservatively estimates that 22,000 survivors of rape will need support. Fear of sexual violence means that women and girls stay in hiding, unable to seek food.

Humanitarian agencies have been slow to respond, impeded both by the insecurity and by numerous bureaucratic obstacles placed in their way by the Ethiopian authorities. To operate in a context such as this, aid workers need communications equipment.

The UN officially claims that aid distributions have reached 2.8 million people. Privately, the humanitarian workers say that is far too rosy.

Many of those have received one distribution of rations, perhaps 30kg of flour - enough to feed a family for 10 days. Luckier ones have got two allocations.

And there are persistent reports that aid offloaded from trucks is then stolen by troops. Some villagers report that Eritrean troops show up immediately after aid distributions and take the food.

Independent estimates are that just 13% of the 5.2 million people in need are getting aid.

AFP

AFPHumanitarian workers have been killed - most recently on 28 May. The Ethiopian army routinely blocks aid workers travelling deep into rural areas, accusing them of helping the rebels.

Local officials allege that all sides in the conflict are involved in looting aid. However, the UN reports 129 incidents of "access violations" by Ethiopian and Eritrean troops and militia obstructing aid last month, and only one case by the Tigray Defence Forces, as the rebels call themselves.

At Thursday's roundtable, Ms Power summarized her discussions with experienced aid workers: "The worst humanitarian conditions they have ever witnessed." This is the consensus among donor nations.

Plea for ceasefire

There is also a consensus on what needs to be done to mitigate the tragedy - it is now too late to prevent it.

Number one on the action list is what Jan Egeland, head of the Norwegian Refugee Council, calls a "famine prevention ceasefire".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis includes a cessation of hostilities, protecting civilians at risk of violence including rape, and unimpeded humanitarian access.

None is straightforward. Last week, the Ethiopian government spokesperson insisted that imminent military operations would deliver a decisive victory - essentially ruling out a ceasefire.

Responding to US calls for Eritrean withdrawal, the Eritrean foreign minister accused the Biden administration of "stoking further conflict and destabilization".

On Tuesday, the TPLF said it welcomed aid and would be ready to help distribute it - but made no mention of a ceasefire.

'Don't wait to count the graves'

Humanitarian agencies have developed ways of operating in conflict zones - but they require the cooperation of the warring parties.

There is no sign of that, with the Ethiopian government insisting that the rebels are "terrorists" and there should be no cooperation with them, even on life-saving operations.

The humanitarian presence in Tigray is increasing, but far too slowly to make a real difference.

The pre-war aid infrastructure has been mostly destroyed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMore resources are needed too. The US just announced an additional $181m (£128m) in aid, signalling that it hoped other donors would step up too.

Meanwhile, food security is fast deteriorating in the neighbouring regions of Amhara and Afar, as the ripples of the war and a deepening nationwide macro-economic crisis are disrupting livelihoods and deepening poverty. There are also warnings of escalating food needs in Sudan.

What is conspicuously lacking is action at the United Nations Security Council. Resolution 2417, on armed conflict and hunger, was passed three years ago with precisely crises such as this in mind.

Seven months after the war erupted - and the first alarm was sounded - there hasn't been a single public session of the UN Security Council on what is now the world's gravest humanitarian crisis.

Resolution 2417 empowers the UN to impose sanctions on individuals and entities that obstruct humanitarian operations, and warns that the use of starvation as a weapon of war may be a war crime.

This weekend the G7 leaders are likely to step up the pressure on Ethiopia and Eritrea to comply with their demands for immediate humanitarian action.

As US Special Envoy Jeff Feldman warned, we "should not wait to count the graves" before declaring the crisis in Tigray what it is: a man-made famine.

Alex de Waal is the executive director of the World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in the US.