Kenya's Thandiwe Muriu: Standing out in camouflage

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

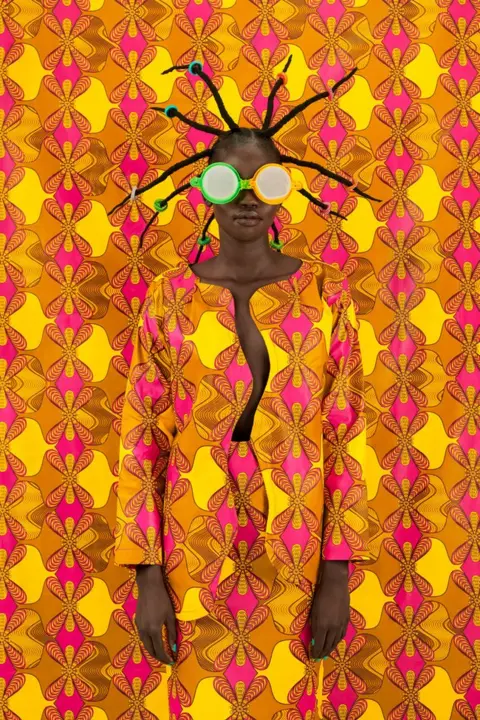

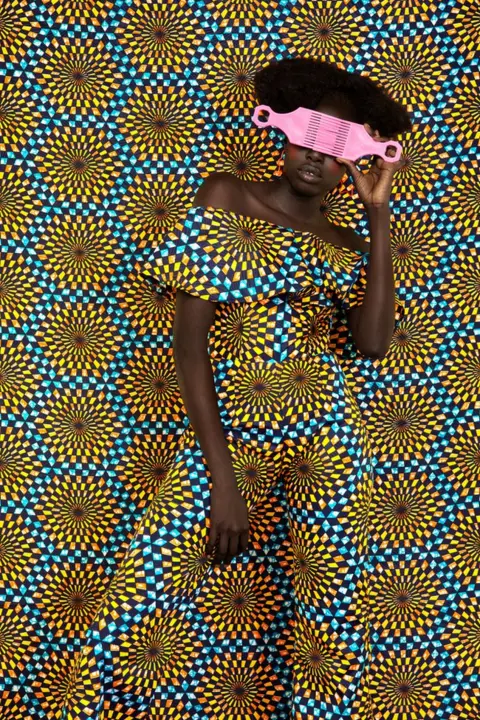

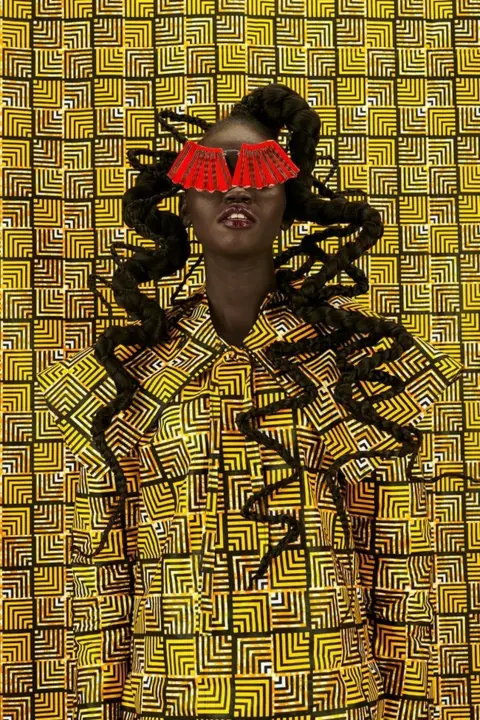

Photographer Thandiwe Muriu wants her models to both blend in and stand out at the same time.

The images in her Camo - short for camouflage - series create an optical illusion where the person in the photograph almost disappears yet it is impossible to ignore her.

The young Kenyan's playful work has the feel of a glossy high-fashion magazine but also has a deeper meaning.

"I love fashion photography, I could do that all day, but I realised it needs to be fashion photography that is a reflection of who I am and my background," she tells the BBC. "That is how the Camo series came about."

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

The funky fabrics, elaborate hairstyles and improvised eyewear are an attractive and witty celebration of the 30-year-old's culture.

But there is also a critique.

Muriu says the series is "a little bit of a personal reflection on how I felt I can disappear into the background of my culture.

"And my experience as a commercial female photographer was realising that very quickly - because of the cultural context - I can be dismissed and disappear."

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

She was self-taught, schooled, in her words, at "the university of YouTube", but her father provided the initial impetus.

Raising a family of four daughters and no sons he was keen to buck the patriarchal assumptions, Muriu says.

He taught them practical skills like how to change the tyre on a car, how to barbecue and, most significantly, how to use a camera.

And when it came to choosing a career she was encouraged to follow her passion for photography. For her it was the "perfect blend of science and art".

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

Inspired by the images she saw in her sister's Vogue magazine collection, Muriu went into commercial photography, which in Kenya is male-dominated.

"I'm small, I look very young and so oftentimes the biggest thing I would experience is people dismissing me. I would walk on to set and people would talk to my assistant who was male, assuming he was the photographer rather than me.

"I had to learn to be brave and bold and say: 'Hi, I'm in charge.'"

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

As she was developing her craft, Muriu was helped by a group of photographers who were breaking new ground in the country as homegrown talent. She was encouraged by one of them, Osborne Macharia, to find her own creative project away from the commercial work.

This led to the birth of Camo in 2015.

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

"Initially I was exploring myself as a creative," she says. But even the early work has what she calls "trademark Thandiwe" - meaning that "everything is very bold, almost in a quirky way".

"I think with the earlier images it was all about celebrating these beautiful fabrics and this vibrant culture that I live in and see every day."

She very deliberately chose a dark-skinned model to challenge what she says is a culture of bleaching in Kenya, where some see lighter complexions as more beautiful.

The first model she used also had a gap in her teeth, which in her Kikuyu culture, she says, "is viewed as a symbol of beauty". And she had to have natural hair.

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

Muriu wanted a 10-year-old Kenyan girl to see the pictures and be able to say: "That's me."

Looking at the images it is obvious that constructing them is a meticulous process.

It starts with choosing the fabric, which Muriu describes as one of the hardest but most enjoyable parts.

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

Spending hours in Nairobi's fabric shops, she sifts through floor-to-ceiling piles of cloth imported from across the continent.

She is looking for "something that's really loud with an almost psychedelic quality, as if the fabrics are alive and moving and confusing the eye". It is recognisably African but not necessarily the traditional designs.

"We're in this new Africa, this new generation, where we love our prints but we're not going to wear them in traditional ways."

Thanidwe Muriu

Thanidwe Muriu

Another key stage is the hair. As the project developed, Muriu became more intentional about her exploration of African beauty.

She researches historical and traditional hairstyles. Then with the help of a stylist gives them a "modern, funky twist but they are based on hair that our ancestors actually used to wear", she says.

"It became more than just looking at beauty. It was about asking: 'What are some of the symbols of beauty that we have lost?'"

The eyewear, made from soft drinks cans, plastic tea strainers, clothes pegs, bottle brushes and other objects represent the innovative way that many everyday things in Kenya are repurposed for other uses, Muriu says.

Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu

They also add to the humour of the images which the photographer wants to make visually stimulating and enjoyable, while at the same time tackling some very profound issues.

And the series is not over.

"I will always do more. A lifetime challenge would be to try and catalogue all of them and become the first modern archive of our hair and our fabric. Why not?"

All pictures by Thandiwe Muriu.