Measuring Africa’s Data Gap: The cost of not counting the dead

Getty Images

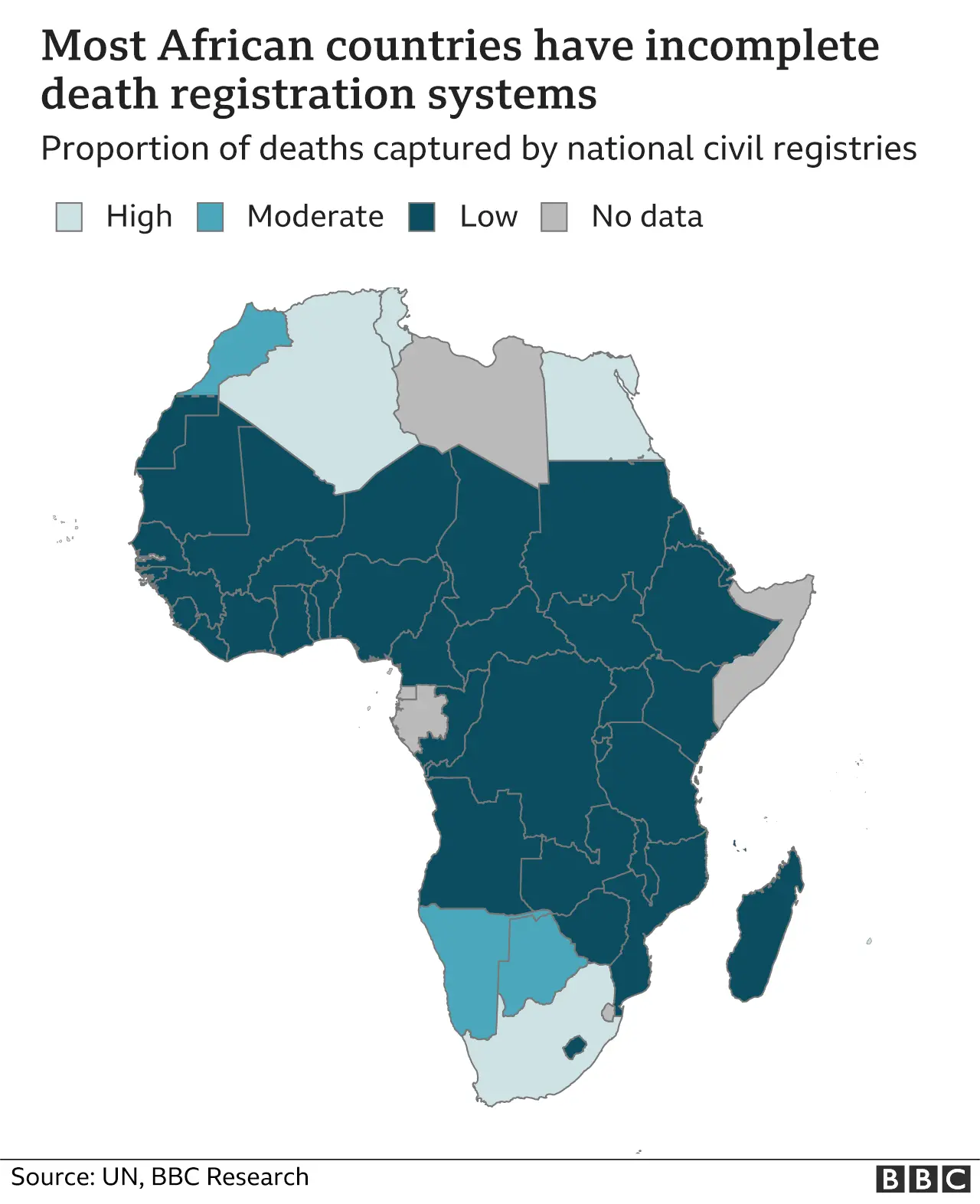

Getty ImagesOnly eight African countries out of more than 50 have a compulsory system to register deaths, a BBC investigation has found.

This is not just a failure of the state to recognise individual tragedies but has enormous implications for the making of government policy.

All but two countries in Europe - Albania and Monaco - have a universal death registration system, and in Asia, just over half, analysis of UN data shows.

But in Africa it is only Egypt, South Africa, Tunisia, Algeria, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles and Mauritius that have what are called functioning, compulsory and universal civil registration systems - known as CRVS systems - which record deaths.

All of the countries surveyed by the BBC, working with researchers from the UN's Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), do have some sort of death registration.

But it is often on paper and not available in a shareable digitised form. The information may be used in a local area but cannot calculate mortality trends on a national level.

In the wake of the Ebola epidemic, and now Covid-19, having an accurate picture of who is dying, from what and where, is crucial when it comes to allocating resources and funding.

This also has implications for tracking maternal and child mortality as there are children whose birth and untimely death go unrecorded.

This not only robs them of a "right to an identity", in the words of William Muhwava - the head of demography at the UNECA based in Addis Ababa - it also means that lessons are not learnt.

"In order to help the living, we need to count the dead," UN Population Fund demographer Romesh Silva told the BBC.

Those who are missed out on the registers are often the poorest and socially excluded, he adds, and the absence of information about their deaths means that measures to deal with the causes are sometimes not taken.

"Despite investments, CRVS systems remain dysfunctional, forcing governments to rely on surveys... which by the time they are published are already outdated," says Irina Dincu, from the Centre of Excellence for CRVS systems.

AFP

AFPWhen it comes to coronavirus there is a concern that its true extent in some countries is not fully understood.

It has been widely reported that Africa's Covid-19 death toll is far lower than in other parts of the world.

Expertise in epidemic control, a swift response in some countries, the relatively young population and cross-immunity from other coronaviruses are all thought to have had an impact.

But data scientists say that calculating a key indicator of the pandemic's fallout - known as "excess deaths" - is impossible in most countries because of the lack of CRVS systems.

Measuring the Covid-19 death toll

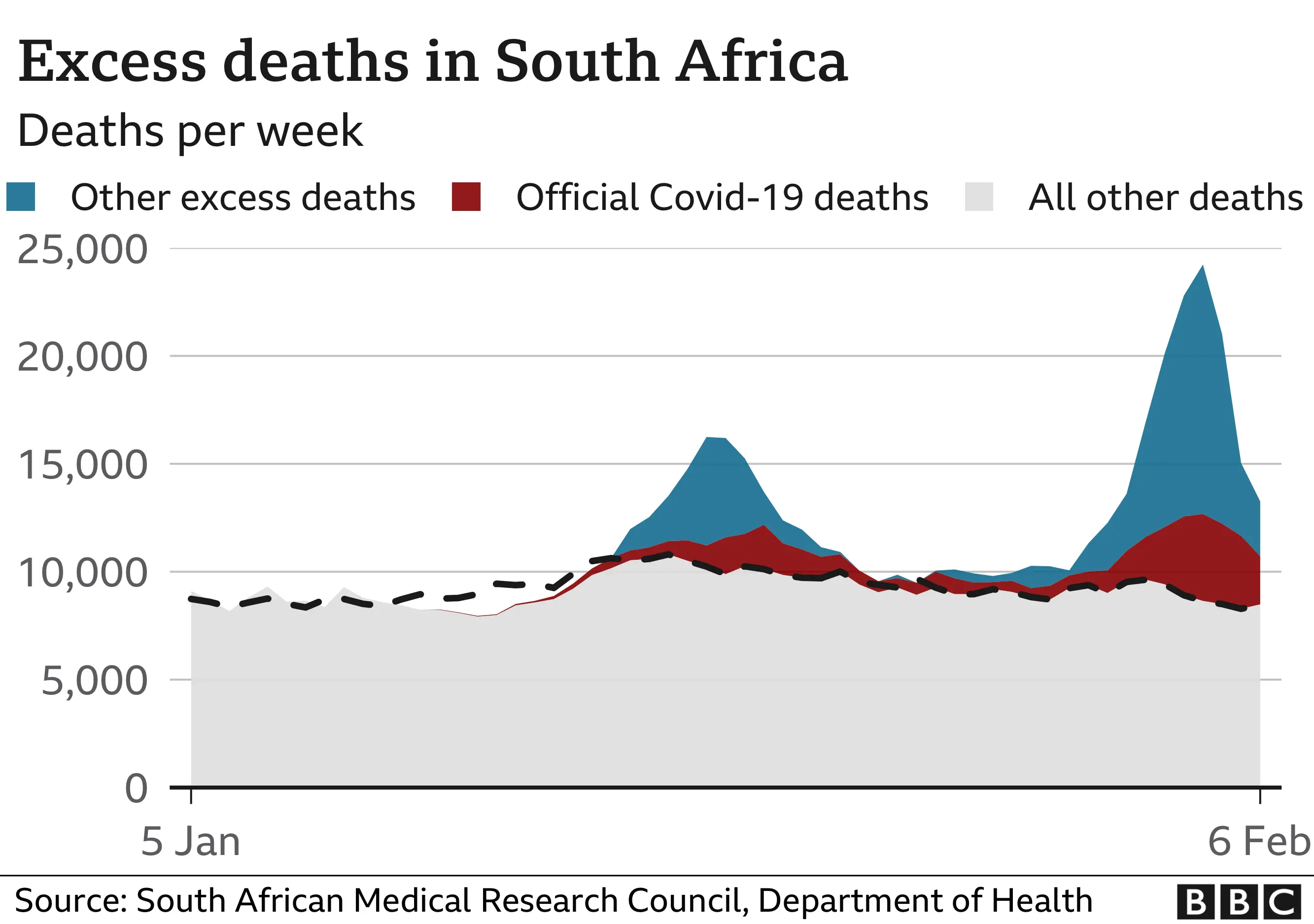

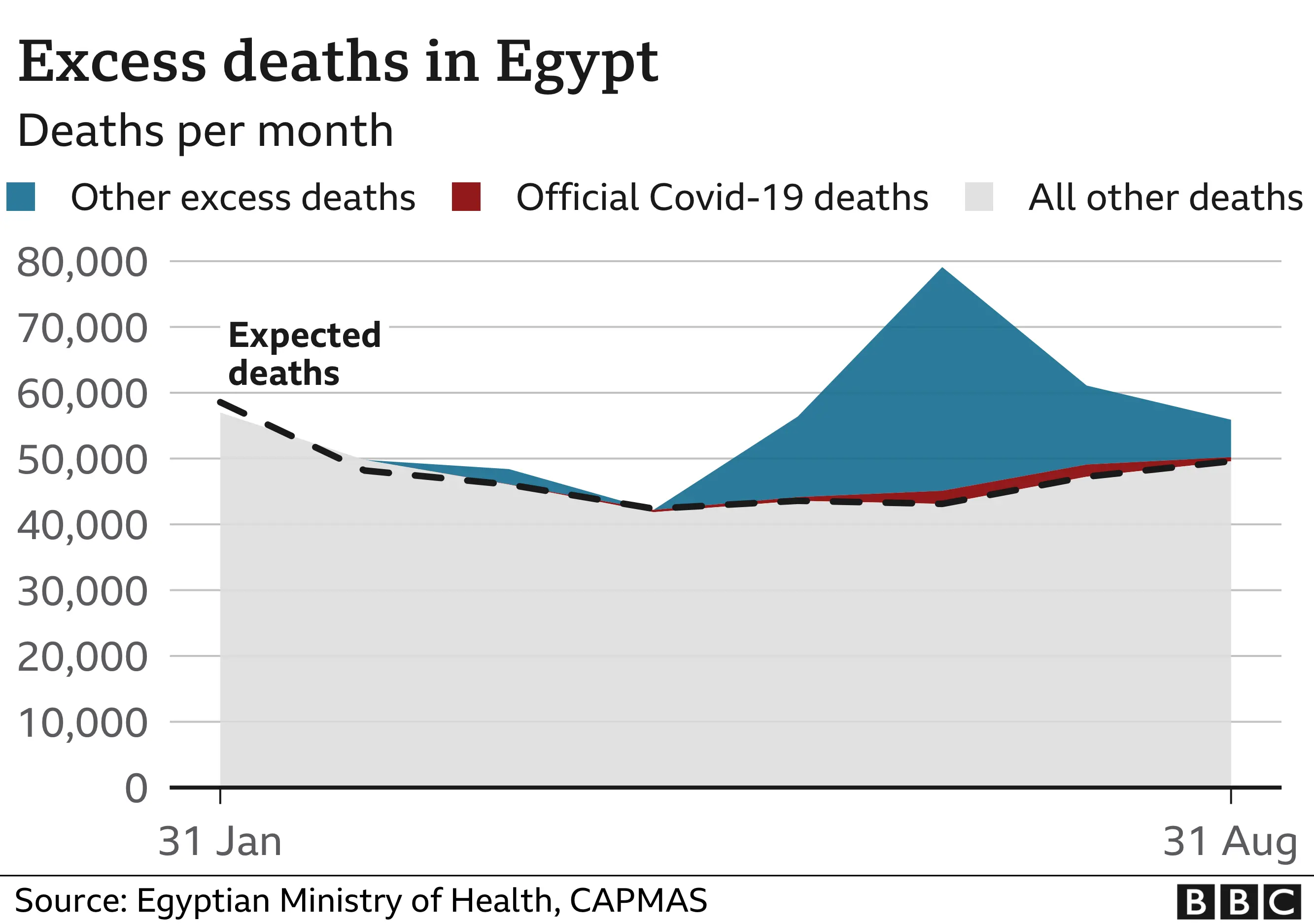

Excess deaths is a measure which compares the actual deaths over a period of time with the number of deaths expected based on the same period in previous years. But it relies on the full registration of deaths.

Looking at excess deaths gives a sense of the overall loss of life caused directly by Covid-19.

It also shows deaths caused indirectly by the pandemic because of factors such as overstretched health systems, fear of attending hospital and an economic downturn.

A Lancet study across 118 low-income and middle-income countries estimated that the continued disruption of health systems from Covid-19 could result in 1,157,000 additional child deaths and 56,700 additional maternal deaths.

South Africa and Egypt are among the eight countries which do have functioning death registers, so calculating excess deaths in both countries is possible, and the results are telling.

By early February, South Africa had recorded nearly 138,000 excess deaths since the pandemic began - that is almost three times the official figure given for Covid-19 deaths.

To break it down: 46,200 of these people were officially recorded as having died with coronavirus and there are death certificates to prove it.

This means the other 91,500 were either undiagnosed, or died as an indirect consequence of the pandemic such as delayed cancer treatment or fear of going to hospital.

At the height of the pandemic in late last July, South Africa experienced 54% more deaths than was expected for that time period.

Although when the lockdown was first imposed, fewer deaths were recorded than normal, presumably because of fewer cases of alcohol-related violence and road accidents.

Thanks to Egypt's comprehensive registration system, it is possible to calculate that there were more than 68,000 excess deaths between May and August last year.

In June, the number of recorded deaths was almost double what would usually be expected.

On average, official Covid-19 deaths made up under 10% of those additional losses.

But for most countries on the continent there is no way to reach any conclusions like this as the data is so sparse.

In 14 countries a maximum of only one in 10 deaths are recorded, including in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon.

Over half of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa only keep handwritten death records.

Certain states, such as Eritrea and Burundi, have no legal requirement to register or collate deaths at all.

Eritrea has recorded only seven Covid-19 death to date and Burundi, just three, although there was speculation that the virus was a contributing factor in the unexpected death of Burundi's former President Pierre Nkurunziza last year.

Nigeria, Africa's most populous country, recorded only 10% of all deaths in 2017.

The pandemic further "paralysed all the civil registration activities" in the country, which were not deemed an essential service, according to a UN report in April 2020.

This could explain why the number of Covid-19 deaths per million people remains relatively low there.

Nigeria has recorded nine Covid-19 deaths per million, compared to the global average of 316.

Meanwhile, South Africa has recorded 827 Covid-19 deaths per million and Tunisia 659 - the two highest in Africa.

But it is important to take into account that these countries have good registers that capture most deaths - 92% and 95% of the population, respectively.

What is being done?

The BBC and UNECA's research has created the most up to date and comprehensive assessments of the death registration systems on the continent.

It was also discovered that many countries are making progress in bridging the data gap.

The Central African Republic (CAR) has one of the lowest performing CRVS systems on the continent following years of conflict, which is still ongoing.

In 2017 only 2% of estimated deaths were registered in the country. Twice as many male deaths were recorded as female - and then only in the capital, Bangui, and its outskirts.

Elvis Franck Matkoss, head of the statistics department at the Ministry of Economy, Planning and Co-operation, told the BBC that "the government attaches particular importance to CRVS and its fundamental role in promoting good governance".

He added that the CAR was making great efforts to improve on its 2% coverage through the modernisation of registration centres and the creation of a more centralised system.

Mr Matkoss said the government was also providing funding to help communities register their dead, as well as promoting free birth certificates for all children.

Senegal and Rwanda are both working with a US non-profit organisation, Vital Strategies, to put together historic mortality data that can be compared to deaths during the pandemic - using a method called "rapid mortality surveillance".

Five other countries - Togo, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Ghana - are working with the African Field Epidemiology Network to do the same.

'Verbal autopsies'

Chad and Liberia are asking community health workers to notify the authorities about deaths that occur outside of hospitals.

They are using "verbal autopsies" - interviewing next of kin about the deceased - a low-cost solution to understand major causes of death in a specific region.

Some countries are using mobile technology to collect, manage and archive data about deaths.

In Rwanda and Mozambique, people can use smartphones to register deaths on an electronic system, allowing relatives to report deaths while socially distancing.

In Uganda, the Civil Registration Office has set up the Mobile Vital Records System for the registration of births and deaths in health centres and at a community level.

Over the next decade, data scientists hope this kind of innovation will help more countries on the continent to reach their universal death registration targets.

The BBC's research has highlighted some of the problems and the UNECA's Mr Muhwava said that it had brought "to the fore the challenges that CRVS systems in Africa face in documenting death events".

CREDITS

Data journalist: Krystina Shveda

Journalist: Kevyah Cardoso

Senior investigations producer: Louise Adamou

Executive producers: Jacky Martens and Nick Ericsson

Researchers: Maxime Koami Domegni (Senegal) Saikou Jabai Suware (The Gambia), Boubacar Diallo (Guinea), Yasine Mohabeuth (Comoros), Carlos Tobias (Togo), Vincent Niebede (Chad), Alberto Dabo (Guinea-Bissau), Serge Tomondji (Burkina Faso), Crispin Dembasse (Central African Republic), Curtis Slimar (Zambia), Gregory Gondwe (Malawi), Awedni Daweja (Tunisia), Abdelrahman Abutaleb (Egypt)