The orphans of Angola's secret massacre seek the truth

Valles family

Valles familyA massacre in Angola that followed a split in the governing MPLA party not long after independence has been shrouded in secrecy and fear for more than four decades. But some of those affected are coming together to demand answers and have been speaking to the BBC's Mary Harper, some for the first time in public.

"My parents were last seen walking into the Ministry of Defence, hand in hand."

That was more than 40 years ago, when João Ernesto Van Dunem was a three-month-old baby. He never saw his mother and father again.

He does not know where or how they were killed. He does not know where they are buried.

His parents - José Van Dunem, 27, and Sita Valles, 26 - together with other young Angolans, had accused the ruling elite of prioritising personal wealth and power over the good of the country.

Van Dunem family

Van Dunem familyJosé Van Dunem, who was a senior military official, and a fellow MPLA central committee member, Nito Alves, who had been a government minister, led the criticism from within. This led to their expulsion.

There are many versions of what happened next.

The authorities accused what they described as the "fractionistas" or "splitters" of staging an attempted coup on 27 May 1977.

Members of the group said they did no such thing; rather they had organised a mass demonstration and a takeover of the radio station to call people on to the streets of the capital, Luanda, in order to pressurise President António Agostinho Neto to clean up his government.

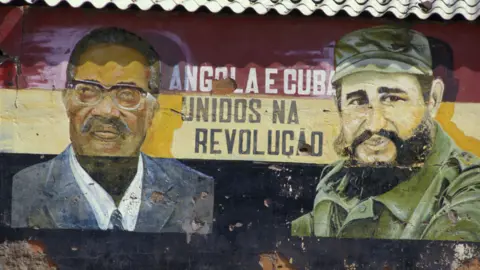

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe result was bloodshed.

Mr Neto called in loyal sections of the army, supported by Cuban troops, and the massacre began.

Thousands, including many of the country's young intellectuals and party activists, were imprisoned, tortured and killed.

Those in authority at the time, including Defence Minister Gen Henrique Teles Carreira, known as Iko Carreira, put the number at 300.

Amnesty International says 30,000 died in the purge. Some say as many as 90,000 were killed.

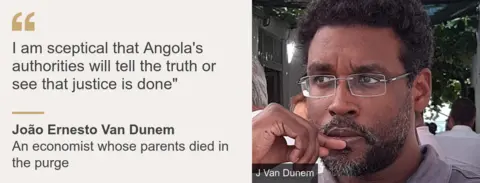

"The 27 May decapitated progressive thinking in the country," says João Ernesto Van Dunem, now an economist at the Catholic University of Angola.

"I am sceptical that Angola's authorities will tell the truth or see that justice is done."

'Witch-hunt'

In May 2017, four decades after their parents disappeared, 24 of the now adult children, including Mr Van Dunem, wrote an open letter to then-President José Eduardo dos Santos, demanding answers. They received no reply.

In January 2018, they set up an association of orphans, named M27.

Vieira Lopes family

Vieira Lopes familyThe "M" stands both for "May", the month of the incident that triggered the killings, and for "Memory".

Members of M27 have a set of key demands, which they say will restore the dignity of the dead, and see them cast as victims not villains.

- They want the remains of their parents recovered and death certificates issued

- They want a list of all the people who were killed

- They want a memorial built to honour them. And they want the truth to be told.

"Imagine what 40 years of silence can do to your mind. The killing of my father created this huge gulf between my motherland and myself," says Henda Vieira Lopes, another member of M27, who works as a psychologist in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, Angola's former colonial ruler.

"For a long time I did not want to return to Angola as I feared I would feel like an orphan in a strange land."

Mr Vieira Lopes' father, Elisiário dos Passos Vieira Lopes, worked in a hospital in the eastern province of Moxico. He says all of its staff were executed.

"It was a witch-hunt, like a fire in the savannah, running out of control."

Silence, pain and mystery

Some members of M27 say one reason they have decided to break their silence after all these years is because they now have children of their own.

"My seven-year-old son has started asking questions about his grandparents," says Mr Van Dunem.

"Where are they? Why did they die? Our aim is to prevent this heavy burden of unsolved questions being passed on to the next generation."

Many older relatives of those who were killed, and who themselves survived the purge, do not want to talk about what happened.

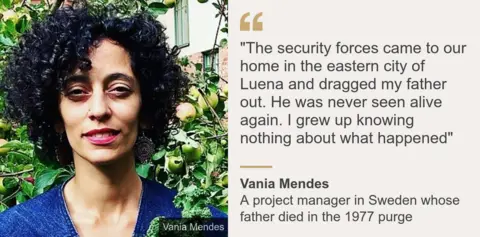

"I was born on 15 May 1977, 12 days before the massacres began," says Vania Mendes, a project manager in Sweden.

"The security forces came to our home in the eastern city of Luena and dragged my father out. He was never seen alive again.

"I grew up knowing nothing about what happened. The family never spoke to me about it. It was very hard to grow up in an environment of silence, pain and mystery.

"My mother still has a lot of fear and rage towards Angola. She was in mourning for years, dressing in black until I was seven or eight years old."

'It's not about revenge'

In 1977, Afonso Carlos António was jailed for 16 months. He now works for the Angolan Ministry of Culture. After 43 years he has finally decided to break his silence.

"I am not happy with the way opinion makers say the survivors of 27 May are traumatised and want revenge," he says.

AFP

AFP"It's not about that at all. It is about honour and truth and a better Angola. In order to have reconciliation the truth has to come out. Only then can we have healing."

Mr António does not want to go into detail about what happened to him in prison.

"Unlike other political prisoners, I was not tortured physically. I was psychologically and emotionally tortured."

You may also be interested in:

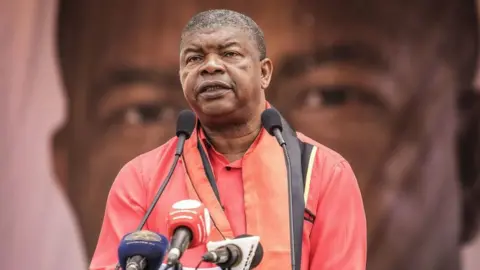

In September 2017 Angola got a new president, João Lourenço, bringing to an end Mr dos Santos' 38 years in power. With him came a degree of change.

In April 2019, Mr Lourenço set up a commission to look into all acts of political violence since independence in 1975, including the 27-year civil war with the Unita rebels, which ended in 2002, and the events of 1977.

"We want to believe the government is acting in good faith but we are sceptical," says Mr Antonio.

"There were no discussions with survivors before the commission was set up, its time frame is too short, and the different periods of violence have been diluted by all being lumped together."

The commission, which will run until the end of July 2021, insists it is giving "special attention" to the events of 27 May and that it has set up a mechanism for issuing death certificates.

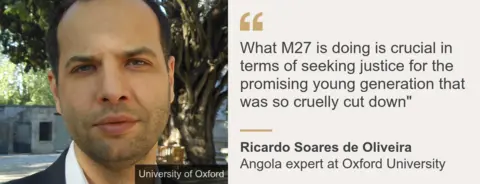

"What M27 is doing is crucial in terms of seeking justice for the promising young generation that was so cruelly cut down," says Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, an Angola expert at Oxford University.

"I am not completely suspicious of Mr Lourenço's commission. It will not change everything but at least it opens a door to a conversation that was previously impossible."

But the fear remains.

"Finally, I have discovered I share a similar story to others," says Ms Mendes.

'We can't mourn without the truth'

"I am no longer alone. But the 27 May remains a taboo subject. When I try to speak about it to my family in Angola they tell me to stop. They say it is too dangerous."

AFP

AFPMr Vieira Lopes says such sentiments are shared: "My mother didn't want me to sign the open letter to Mr dos Santos.

"Other orphans didn't want to sign it because they feared it might attract retaliation. Some said signing the letter was like putting a target on my back."

Mr Vieira Lopes' mother had reasons to be afraid. Under Mr dos Santos, people were arrested for taking part in demonstrations commemorating those who died in 1977.

A 17-year-old boy, who shares Nito Alves' name, was held in solitary confinement in 2013 after taking part in a small anti-government protest.

M27's purpose is political, but also highly personal.

"If you don't know where your parents are buried and you don't have their death certificates, you cannot mourn them," says Mr Vieira Lopes.

"Our ancestors have not been put to rest, and if they are not allowed to rest, neither can Angola."