Victor Olaiya: Nigeria's 'evil genius' trumpeter who influenced Fela Kuti

MYDRIM GALLERY

MYDRIM GALLERYNigeria has been mourning music legend Victor Olaiya, who created Nigeria's highlife rhythms and influenced a generation of musicians including Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. Nduka Orjinmo looks back at the life of the trumpeter, who died last month at the age of 89.

Just like the well-turned out government filing clerk that he was, Olaiya always carried a pen in his breast pocket. This was not for noting instructions that had to be precisely followed, but rather because he needed to write down the musical notes and phrases as they came to him.

This was at the beginning of the 1950s, his early days as a performer, when the trumpeter was trying to create Nigeria's highlife rhythms.

More musician than bureaucrat

At this stage, music was something he did in his spare time and Olaiya thought he had lost his job in the civil service when his boss saw a newspaper photo of him performing at a nightclub.

Instead, he was told that he was a better musician than a bureaucrat at the survey department of Lagos mainland local government.

He left the job and took on music full time.

Born to wealthy Yoruba parents in the southern city of Calabar, Olaiya had an early start in music.

His father was a church organist and his mother a folk singer from the western city of Oyo.

He was also influenced by Caribbean calypso and included the popular song Sly Mongoose in his repertoire that he recalled first hearing when he was nine years old.

As a teenager, though, he was taught Western classical music, and played the clarinet and French horn in his school orchestra in eastern Nigeria.

Years later, wielding his gold trumpet and dabbing his face with a white handkerchief, Olaiya would perform a new type of music in Nigeria that would go on to inspire a young Fela Anikulapo-Kuti among others.

Getty Images

Getty Images

After his secondary school, Olaiya moved to Lagos where he joined the Lagos City Orchestra and then the band of composer Sammy Akpabot, playing ballroom music for wealthy urban audiences.

But it was as the head of Bobby Benson's Alfa Carnival Group that his talent would be properly nurtured.

Benson took a number of musicians under his wing and it was here that Olaiya polished the skills that would help him form his own band, the Cool Cats.

Listening to the recordings now, the gentle swinging rhythm and the prominence of the horn section, you sense a sepia tinge to Olaiya's songs.

MYDRIM GALLERY

MYDRIM GALLERYThey evoke memories of the fading British Empire and transition to independence, conjuring up images of afro hair combed into a dome, of middle-class Nigerians appearing overdressed in tuxedos and gowns with a cigarette neatly tucked between the fingers.

By the late 1950s, the colonial administrators were on their way out and a young generation of educated Africans was about to take over.

As the disco bars and ballrooms gradually thinned out of the British and their music, in stepped the elite class of Africans seeking that same high life but fused with their own culture.

And the bands responded to satisfy their new patrons, incorporating local rhythms and melodies into their repertoire.

You may also like:

The songs were romantic and the lyrics, which to today's eyes appear sexist, often used erotic imagery.

Olaiya's 1961 track Adelebo Tonwoku (Single Lady Looking for a Husband) says that if a woman, referred to as "Cinderella shaking her buttocks", finds a husband she should "forgo education".

As a musical term, highlife was first used in Ghana in the 1920s to describe a band playing a fusion of foreign and local instruments driven by multiple guitars and horns.

Olaiya's influence came from Ghana, as he was a keen admirer of the Tempo band of highlife legend ET Mensah, who toured Nigeria multiple times from 1951.

When Olaiya formed his Cool Cats band, he adopted Mensah's style and had Ghanaian Sammy Lartey as saxophonist. Years later, Olaiya and Mensah would release a joint album.

In bombastic style, Olaiya was once described by a newspaper editor as "the evil genius of highlife", perhaps because once someone heard his music it was impossible not to dance.

His music became so popular that in 1960 he played at the party to celebrate Nigeria's independence in front of Queen Elizabeth's sister, Princess Margaret.

Fela comes to Olaiya

Olaiya was a multi-linguist and sang in Twi, Igbo, Efik, Pidgin and Yoruba and his band would go on to serve as a training ground for musicians who would revolutionise music in Africa.

Chief among those that interned with Olaiya was Fela, creator of the Afrobeat genre and arguably Nigeria's most influential musician.

Fresh from secondary school in 1957, Fela spent time playing with Olaiya's Cool Cats in Lagos and headed another of the maestro's bands.

Olaiya recognised a prodigy and gave him a platform, in the same way that he had been supported by Benson.

Fela's drummer, Tony Allen, was also among those who played with Olaiya. Other notable musicians that passed through his band were guitar wizard Victor Uwaifo, juju musician Dele Ojo and saxophonist Yinusa Akinnibosun.

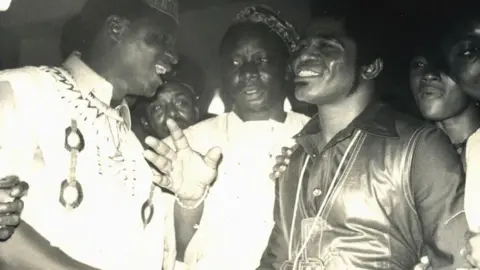

MYDRIM GALLERY

MYDRIM GALLERYBy 1970, under the influence of James Brown, Olaiya had branched into soul and funk music. His Up-to-Date Mover album of that year included five tracks co-written with Brown.

But Olaiya will forever be associated with highlife, and this gradually faded from the scene until the genre became a stacked collection of dusty vinyl for senior citizens who hung onto the memories of an era when "things were good".

The Cool Cats were no longer cool, as first Fela's Afrobeat and later Afro hop swept succeeding generations off their feet.

Olaiya tried to keep up in later decades by doing things like shooting music videos but he never looked comfortable with the format.

He was used to the disco bars, the big orchestra and the larger-than-life bands performing for dandy crowds.

Recognised by a later generation

There were attempts to introduce his music to a new audience.

In 2013, Tuface Idibia, a music legend in his own right, remixed Olaiya's Baby Jowo. It was a homage to another era but only underlined how things had changed.

A handful of highlife musicians are still scattered in the eastern and western parts of Nigeria but their tunes are now mostly heard at funerals.

When Olaiya is laid to rest, perhaps a band led by an immaculately turned out trumpeter will be at the front of the procession?

And when he is lowered into the ground, it may be more than flesh that is returning to dust. The highlife music he pioneered may just be buried along with him.