Remembering Nigeria's Biafra war that many prefer to forget

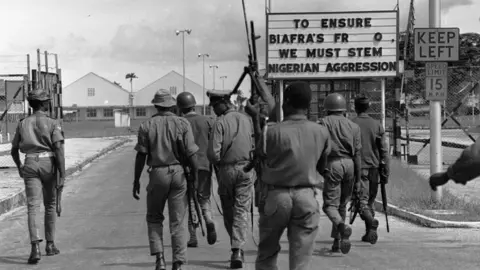

Romano Cagnoni / Getty Images

Romano Cagnoni / Getty Images

The deaths of more than a million people in Nigeria as a result of the brutal civil war which ended exactly 50 years ago are a scar on the nation's history.

For most Nigerians, the war over the breakaway state of Biafra is generally regarded as an unfortunate episode best forgotten, but for the Igbo people who fought for secession, it remains a life-defining event.

In 1967, following two coups and turmoil which led to about a million Igbos returning to the south-east of Nigeria, the Republic of Biafra seceded with 33-year-old military officer Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu at the helm.

The Nigerian government declared war and after 30 months of fighting, Biafra surrendered. On 15 January 1970, the conflict officially ended.

The government's policy of "no victor, no vanquished" may have led to a lack of official reflection, but many Nigerians of Igbo origin grew up on stories from people who lived through the war.

Three of those who were involved in the secessionist campaign have been sharing their memories.

'We thought we were magicians'

Christopher Ejike Ago, soldier

He had just finished grammar school and started training as a veterinary assistant at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN), in south-eastern Nigeria, when the civil war began.

Almost every student he knew became part of the war effort.

He joined the Biafran army and was assigned to the signal unit, whose responsibilities included "active intelligence and eavesdropping on the Nigerian military".

"We thought we were magicians," said 76-year-old Mr Ago.

"The Nigerians who were pursuing us were trained soldiers. We were not. We were drafted into the war, given two days' training.

"Plus the fact that we were hungry. Some of us, our skin was getting rotten. Nobody can fight a war like that."

In January 1966, some senior Nigerian army officers, mostly of the Igbo ethnic group, assassinated key politicians during a coup in the West African state.

Those killed included Ahmadu Bello, a revered leader in the north.

This led to months of massacres against the Igbo living in the north. Tens of thousands were killed while about a million fled to what was then known as the Eastern Region.

Mirrorpix

Mirrorpix

These events sparked the decision to secede, spearheaded by Ojukwu, who was then the military governor of the Eastern Region.

In the months preceding the war, Ojukwu often visited UNN, the only university in south-eastern Nigeria at the time, to meet with students and prepare them for secession.

Mr Ago looked forward to these visits, and joined the crowd who gathered at the university's Freedom Square.

"Once his helicopter touched down, everybody went there and, practically, school shut down.

"He had this incredible sense of humour. He spiked everybody up and we formed songs and were singing and enjoying ourselves."

In the first year of the war, the Nigerian government captured the coastal city of Port Harcourt and imposed a blockade, which cut food supplies to Biafra.

Evening Standard

Evening StandardMr Ago remembers the overpowering hunger that often forced Biafran soldiers to catch and eat mice. He also remembers the last year of the war when his unit was continuously on the move, fleeing the advancing Nigerian army.

"Somewhere in the middle of the war," he said, "the Biafrans made some dramatic successes that gave us hope that we might hold the Nigerians until at least some help from outside came."

By late 1969, all hope was lost.

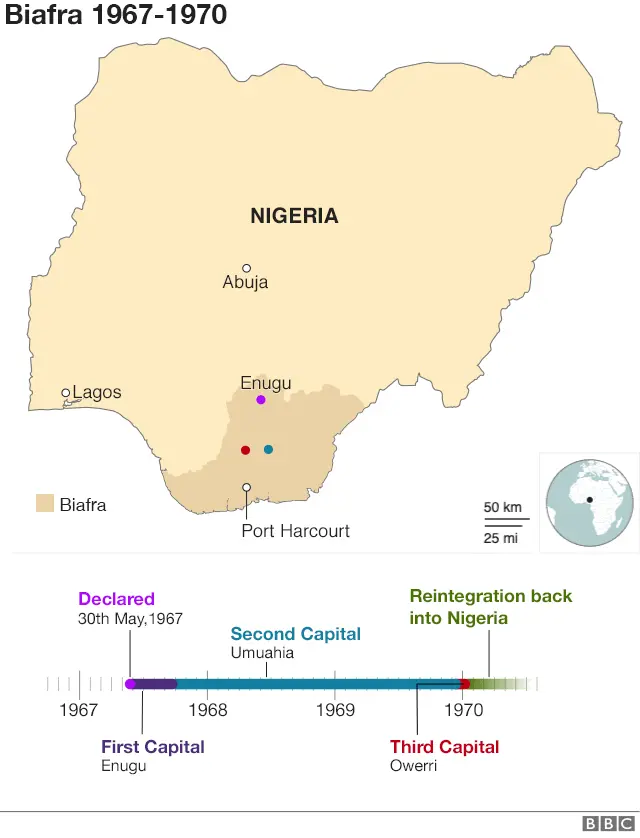

Biafra timeline

- January 1966 - Nigerian government overthrown in what was seen as an "Igbo coup" led by junior army officers

- January 1966 - Lt Col Odumegwu-Ojukwu appointed military governor of Eastern Region

- July 1966 - Second coup masterminded by Murtala Muhammed, Lt Col Yakubu Gowon becomes head of state

- June to October 1966 - Riots in northern Nigeria targeted at Igbos, killing many and forcing up to a million to return to south-eastern Nigeria

- May 1967 - Ojukwu declares independence of the Republic of Biafra

- July 1967 - War begins

- October 1967 - Biafran capital Enugu falls

- May 1968 - Nigeria captures oil-rich Port Harcourt

- April 1969 - Umuahia, new Biafran capital falls to Nigerian forces

- January 1970 - Ojukwu flees Nigeria

- January 1970 - Biafra surrenders

Mr Ago left the army and went in search of his family, whom he had not heard from in more than two years.

He collected his portion from an allocation of raw rice to his unit, then set off towards the village of a relative, where he suspected his parents and siblings would be holed up.

"I had to carry the rice while starving myself, carrying it across rivers and forests until I found them," he said.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Many of his friends and classmates had died at the battlefront. But his family was delighted to see that the son and brother they assumed dead was alive. And they were glad that he had turned up with food.

Hunger killed more Biafrans than bullets and bombs.

When the university was reopened a few months after the war ended, Mr Ago returned to UNN, eventually graduating with a degree in plant and soil science.

"I think we would have done better if we had handled it with a little bit more intelligence," said Mr Ago. "I think now that Ojukwu… thought he was Jesus Christ.

"He thought he could do magic. If he had slowed down and allowed some people who were with him to advise him properly, we would have come out better than we did."

'They only had knives and cutlasses'

Felix Nwankwo Oragwu, scientist

He was a physics lecturer at UNN when the civil war began.

For the next 30 months, he headed the Research and Production (RAP) group comprising Igbo scientists from various fields.

Its primary responsibility was to provide technological support to the Biafran army, which was poorly equipped.

The RAP's most notable product was the "ogbunigwe", a weapons launcher of remarkable and devastating effect which influenced the outcome of many battles in Biafra's favour, according to historical reports.

"Without us, the war would have lasted only about 30 hours," said the 85-year-old.

"When the war started, there was not a single weapon either in a store or anywhere throughout Biafra. They only had knives and cutlasses. No gun, no bomb, no nothing."

In the aftermath of the war, the Nigerian government did not want to impose any form of collective punishment.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Nevertheless, the Igbo faced some devastating consequences, particularly economically as the Biafran currency that people had accumulated became worthless.

Many Igbo still feel sidelined in Nigerian politics, as since the civil war no-one from the ethnic group has become president.

Increasing cries of marginalisation have led in recent years to the emergence of Igbo groups agitating once again for secession, particularly the Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob), formed by UK-based British-Nigerian Nnamdi Kanu.

Mr Oragwu wishes that the Igbo had paid less attention to the scramble for power at the centre, and instead distinguished their region by advancing the technological gains of the war.

"Biafra would have been a technological nation and would have been able to compete with anybody," he said, anger in his voice.

"That is what makes me sad. By this time, we would have been competing with at least South Korea."

The scientist's wartime accomplishments had caught the attention of the Nigerian authorities and he was invited by the government to pioneer a special science and technology programme for the country.

He was behind the setting up of four universities of science and technology in different regions of Nigeria and after retirement he published Scientific and Technological Innovations in Biafra, a book he hoped would inspire young Nigerians.

"Nigeria was programmed by the British colonial authorities not to participate in production and manufacture of global technologies," he wrote in the book.

"The war gave the opportunity to… reject the colonial design."

'An incredible period'

Edna Nwanunobi, teacher

She was teaching English and French in a secondary school in Port Harcourt in southern Nigeria when the civil war began.

While the UK backed Nigeria, France was the most prominent supporter of Biafra.

But English was more widely spoken in Biafra, so translators were needed whenever French officials visited Ojukwu.

Ms Nwanunobi joined the Biafran ministry of foreign affairs as part of a handful of translators who worked directly with Ojukwu.

"The war was an incredible period," said 82-year-old Mrs Nwanunobi. "Everybody was forced to go home so you were forced to fraternise with your people more than any time before.

"And people who worked in every Biafra office were high level people. These were people who were doing all sorts of things and the war forced them out of their positions."

She enjoyed working directly with the Biafran leader, whom she and her colleagues fondly referred to as "Brother OJ".

"He was a gorgeous person," she said again and again. "And he was disciplined. If any meeting lasted more than two hours, he wouldn't be party to it."

Her most memorable assignment occurred after the Biafran military captured six Italian oil workers employed by the Nigerian government.

Officials from different European countries travelled to meet Ojukwu to appeal for their release.

"That was the largest assembly we had," she recalled. "Even the Vatican sent representatives."

During the meeting, Mrs Nwanunobi conveyed to Ojukwu that he stood the risk of losing European support.

He promised to consider the matter, and the Italians were subsequently released.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMrs Nwanunobi met Ojukwu for the last time on 23 December 1969, when she lined up outside his office with her colleagues, to receive a Christmas gift and a handshake from him.

A few days later, she left the country for the Biafran office in Paris. During a stopover of several days in Lisbon, she heard that Biafra had surrendered.

Her first concern was for Ojukwu.

"I was worried that he would come to harm," she said softly. "I didn't want anybody to disgrace him."

Her worry lifted when she learned that her boss had escaped in his private jet, and was granted asylum by Ivory Coast, a francophone country.

Mrs Nwanunobi spent much of the 1970s in Canada before returning to Nigeria in 1977, where she resumed work as a secondary school teacher.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOjukwu himself remained in exile for 13 years. After he was officially pardoned by the Nigerian government, he returned in 1982, with multitudes pouring onto the streets of his home state of Anambra to welcome him.

He died in November 2011 and was given a full military burial in a ceremony attended by then Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan, some other African leaders and members of the diplomatic corps.

Fifty years after the Biafran conflict, Nigeria is still battling to maintain its unity, with various groups, not just the Igbo, calling for the restructuring of Africa's most populous state.

It is probably for this reason that the war is barely mentioned.

The government has nothing to gain by reminding Nigerians that secession happened before and can be attempted again.