Robert Mugabe: My complicated relationship with Zimbabwe's former leader

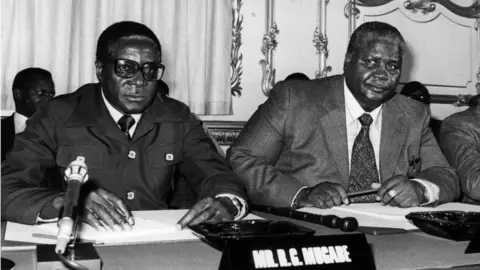

Fairfax / Getty Images

Fairfax / Getty ImagesUntil he was ousted two years ago, Robert Mugabe was the only president I and the other "born frees" - the generation born after independence in 1980 - had ever known.

Mugabe was my grandmother's president, my mother's president, and I thought he was going to be my daughter's president as well. The word "president" for us meant Robert Mugabe.

In school we used to revere him for his linguistic prowess. His speeches were spellbinding and rousing. We sang songs in his praise at school assemblies. Such was our pride to have him as our leader.

I will remember him for being true to his beliefs. He lived a principled life. He never drank or smoked, he ate traditional Zimbabwean food and he was a keen tennis player.

He also presided over the violent repression of his political opponents and the slow decline of his nation into economic ruin. To some he was a hero, to others a villain.

Mugabe was a smart man, always resplendently dressed in a suit and tie. At home he was a good father, fond of his children, particularly his eldest daughter Bona. He had a romantic side to him.

News of his death in a plush Singapore hospital was for me deeply ironic, against the backdrop of a collapsed health system back home. It was perhaps a sign of his selfishness.

His wish was to live until 100 years and to remain in power until he died. He just fell short of both goals.

AFP

AFPFor 37 years we endured his iron-fisted control. I feared him. He was enigmatic and he remained so even when I managed to interact with him in later years as a journalist. There was an aura of invincibility about him. You wouldn't look him in the eye and not blink.

But as a black child living in independent Zimbabwe, it was because of Mugabe him that we were able to obtain a meaningful education. Finally we enjoyed the same rights as white children. His policy of reconciliation in 1980 went a long way to unite black and white people after years of discrimination and conflict, until he later changed his tune.

He always understood the importance and the power of education. His education policies made Zimbabwe the envy of Africa.

AFP

AFPI went to a brand new primary school in the small town of Masvingo, in the south of the country. We used to get fresh milk to drink at break time and a juice and energy biscuits at lunch time.

The ensuing years saw the opening of many technical and teacher's colleges, and universities across the country. Nowadays, if you throw a stone in the capital city of Harare you will likely hit a graduate. But in an illustration of his tainted legacy, most of them are unemployed.

At one point there was universal access to primary health care - another of his achievements - which was undone by Zimbabwe's economic collapse.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn later years, a few Zimbabweans benefited from his empowerment policies, most notably the land reform programme. Some became tobacco farmers, others maize seed producers. They are now enjoying the spoils of owning the means of production.

But many disagreed with the way the programme was implemented and the seizure of the land from Zimbabwe's white farmers after the year 2000 was widely blamed for wrecking our once flourishing economy.

In reality though, the wheels started coming off in 1997, when Mugabe decided to pay liberation war fighters the gratuities they had been demanding in recognition of their sacrifices.

That led to a crash in the Zimbabwean dollar. A year later he decided to send the army to fight in the Democratic Republic of Congo war. In the same year, there were food riots in the country's cities. From that point on, the country never recovered.

My father, a civil servant, was able to send four children to boarding school on his government salary in the 1990s. But a civil servant nowadays can hardly afford the bus fare to get to work.

AFP

AFPMy father can't live on his pension, which has been made virtually worthless by inflation. This is all thanks to Mugabe and his disastrous economic policies.

The war of liberation might have ended with independence in 1980, but Mugabe never stopped fighting. He believed in both pan-Africanism and Marxism. He shared friendships with the likes of Hugo Chavez of Venezuela and Iran's Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

There is no doubt he was a liberator of the country but there is also no doubt that he became an oppressor. His greatest undoing was his love for power. It was so insatiable that at one point he toyed with the idea of creating a one-party state. And that love for power meant he stayed long after he should have stepped aside and enjoyed his retirement with his family.

In Zimbabwean tradition, it is unheard of to celebrate the death of anyone, let alone a former president. While I'm saddened by his passing, I'm also saddened by the state in which he left our beloved Zimbabwe.

A guide to Robert Mugabe

Reuters

Reuters