The Kenyan school that was once a British detention camp

Getty Images

Getty Images

In a school in central Kenya sits a small building that was once used by British colonial forces to torture detainees.

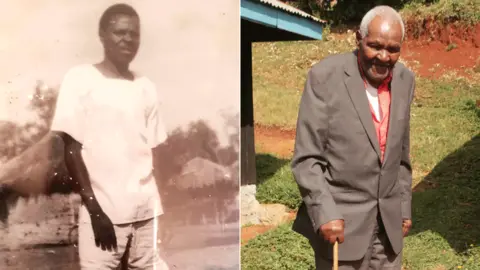

A weather-beaten sign on the outside describing it as a "torture room" serves as a reminder of what it used to be, but 91-year-old Wambugu wa Nyingi does not need to be reminded.

The tiny cell is one of several that were once on the site and in 1959 he spent three months in solitary confinement inside.

With no proper bed and a bucket for a toilet in the corner of the 2.5m (8ft) by 2m room, he was not allowed to leave and was forbidden from communicating with anyone.

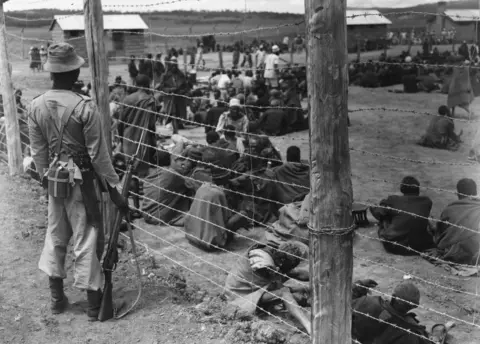

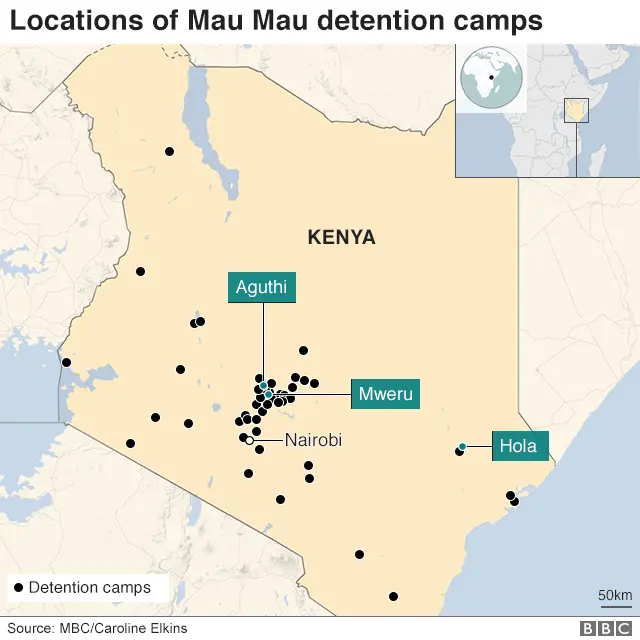

What is now Mweru High School was 60 years ago, the Mweru Works Camp, one of a network of more than 50 detention sites in Kenya.

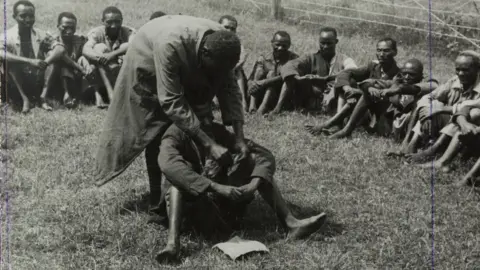

In the camps suspected Mau Mau fighters were held and subjected to brutal treatment, including torture, at the hands of the colonial government.

Wambugu wa Nyingi/BBC

Wambugu wa Nyingi/BBCThe Mau Mau launched a vicious guerrilla war in 1952 to reclaim land that was taken by white settlers after the British founded the East African Protectorate in 1895.

The government responded by declaring a state of emergency and detaining tens of thousands of men in the camps.

At the peak, more than 70,000 people were being held at one time.

Shackled in detention

Militarily the Mau Mau were defeated in 1956, when one of its leaders, Dedan Kimathi, was captured and later executed.

But the state of emergency lasted another three years. Kenyan independence came at the end of 1963 and some historians argue that the Mau Mau insurgency had a role in speeding up the end of colonial rule.

Mr wa Nyingi was one of those accused of having taken the Mau Mau oath. From 1952 to 1959 he was moved through more than a dozen camps, finally ending up in Mweru before being released.

He now has difficulty walking, a result, he says, of being shackled while forced to do hard labour during his detention. He also recalls being deliberately starved, and was beaten unconscious during what became known as the Hola massacre in 1959.

A total of 11 inmates of the Hola camp were found to have been killed by the guards and Mr wa Nyingi, who later regained consciousness, was mistakenly taken to the morgue as one of those who had died.

It was all in an effort to make him renounce his belief in the anti-colonial struggle.

It is thought that overall, more than 20,000 Mau Mau fighters died in the fighting, while they killed at least 1,800 African civilians and 32 white settlers, historian David Anderson has written.

There were many other deaths through harsh treatment and disease throughout the camp network.

Preserving cells

In 2013, after a long legal battle on the part of some Mau Mau veterans, including Mr wa Nyingi, the British government recognised that "Kenyans were subject to torture and other forms of ill treatment" and regretted that the "abuses took place". Thousands of people received compensation.

National Archives

National Archives

At Mweru High School, not far from where Mr wa Nyingi was held in solitary confinement, is a building that was once a cell for detainees.

It is now a classroom, but the rusty barbed wire that can be seen just above the blackboard in the gap between the brick wall and the metal roof hints at its earlier use.

There are more modern buildings in the school campus and, as deputy principal Patrick Karaya says, ideally the former cell would no longer be in use. But he is committed to preserving the few structures dating from the 1950s.

"We have decided that they must remain there," he says. "Some people may think that it's a myth [that this was a Mau Mau detention camp], but if they come and see and look at it, and we encourage them to touch it, they know it's a reality.

"Being an education institution, we always tell the students to value that history, because it is the history that has made us what we are."

There is also an effort to extend the act of remembering beyond those who can visit the school.

A multi-national team of volunteers who make up the Museum of British Colonialism (MBC) have created a 3D digital reconstruction of the camp. Online visitors can take a virtual journey through the camp and its buildings as it once looked.

The museum, which only exists online, is dedicated to what it calls "restorative history". On its website it describes this as an effort to fill in the gaps where history has been "removed, concealed or destroyed".

History relies on physical and documentary evidence, as well as people's memories of events.

But it often also relies on the willingness of officials to want that history to be told. Without that, the evidence can be erased and witnesses are not listened to.

The UK government either destroyed or mislaid documents pointing to systematic torture in the camps, Mr Anderson writes.

At the same time the post-independence government did not want to celebrate a violent and radical movement that could threaten its own vision for the country, Kenyan historian Vincent Simiyu says.

MBC

MBCIt is these twin forces that, in both the UK and Kenya, led to the partial erasure of the history of the Mau Mau and what happened to them. It is not that the violence was unknown, it was that it was barely spoken about in official circles.

The Mau Mau conflict and the broader anti-colonial movement is part of Kenya's school curriculum, but 26-year-old Kenyan MBC volunteer Chao Tayiana was not satisfied by what she learnt.

"Despite growing up in Kenya and going through the education system I still knew very little about the struggle," she says.

Creating 3D digital models

The camps, though concentrated in central Kenya, were dotted across the country. There were also villages where women and children were forced to live.

But after independence in December 1963 these sites either disappeared or were converted to other uses, Ms Tayiana, a digital heritage specialist, says.

She argues that the Mau Mau struggle feels "very abstract".

"We can't relate it to actual human experiences and actual sites... somewhere I can stand on and say 'something happened here'."

That is what is driving her and her fellow volunteers to create the 3D digital models that can be viewed online.

They started with Mweru and nearby Aguthi Works Camp, which is now the site of Kanguburi Girls High School, as some of the physical evidence still existed.

'Forgiving the past'

At Kanguburi, Anthony Maina, who works in the area for the National Museums of Kenya, points to a dip at the bottom of a door into what is now a store room but was once a cell.

It was built just below ground level so the detention camp guards could pour water into the cell to prevent the inmates from lying down, he says, citing the testimony of a camp survivor.

Barbed wire dating from the 1950s can be seen in the roof space of another building that was once a cell and is now also a store room.

Bridgeman images

Bridgeman imagesThe school's name carries an echo of what the site used to be. Kangubiri is a modification in the local Kikuyu language of the English phrase "can go free", reflecting what detainees were told once they were believed to have been reformed.

Despite these clues, local knowledge and the physical evidence of what the sites were used for, decades of official silence followed independence.

In the months building up to independence, founding father Jomo Kenyatta wanted to distance himself from radical land redistribution policies, and was at pains to promote reconciliation with the white settler population.

You may also be interested in:

In August 1963, he reassured a white audience that he had "no intention whatsoever to look backward… We are going to forgive the past".

On another occasion he described the Mau Mau as "hooligans", the historian Mr Anderson says. Writing later in the decade, Kenyatta described the Mau Mau as a "disease which has been eradicated and must never be remembered again".

The act of forgetting was made easier as the Kenyan independence government maintained the official ban on the Mau Mau and it remained a proscribed organisation up until 2003.

This meant that those who had fought with the Mau Mau were unable to speak about their experiences openly and there were no public memorials.

AFP

AFP

Until 2003, admitting membership or being heard talking about Mau Mau meant that "you could be put in jail", the veteran Mr wa Nyingi says.

Since then, there has been more public discussion and a growing recognition of their role, though their exact contribution to independence still remains a matter of debate for historians.

On his part, Mr wa Nyingi wants the Mau Mau to be known as people "who fought for justice without the power of sophisticated weapons".

Standing by one of the structures at Mweru school, Mr Maina, from the local museum, says he wants the state to guarantee the preservation of all the surviving camp structures.

"These buildings are symbols of how our grandfathers suffered fighting for the independence of our country as many died in these cells," he says.

"People have to know that the independence of this country was fought for [and] people shed blood."