Sudan crisis: The ruthless mercenaries who run the country for gold

AFP

AFPThe Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have been accused of widespread abuses in Sudan, including the 3 June 2019 massacre in which more than 120 people were reportedly killed, with many of the dead dumped in the River Nile. Sudan expert Alex de Waal charts their rise.

The RSF are now the real ruling power in Sudan. They are a new kind of regime: a hybrid of ethnic militia and business enterprise, a transnational mercenary force that has captured a state.

Their commander is General Mohamed Hamdan "Hemedti" Dagalo, and he and his fighters have come a long way since their early days as a rag-tag Arab militia widely denigrated as the "Janjaweed".

The RSF was formally established by decree of then-President Omar al-Bashir in 2013. But their core of 5,000 militiamen had been armed and active long before then.

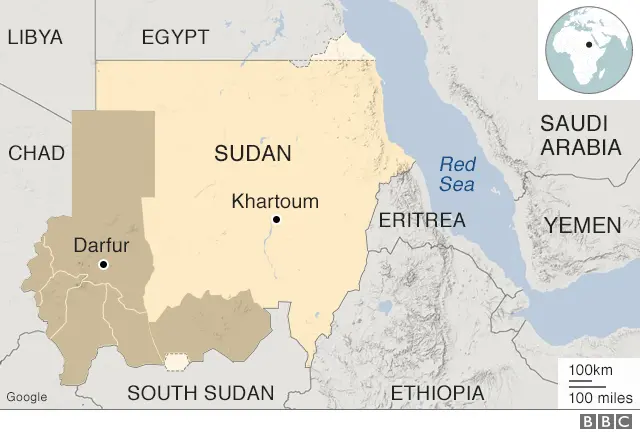

Their story begins in 2003, when Mr Bashir's government mobilised Arab herders to fight against black African insurgents in Darfur.

'Meet the Janjaweed'

The core of the Janjaweed were camel-herding nomads from the Mahamid and Mahariya branches of the Rizeigat ethnic group of northern Darfur and adjoining areas of Chad - they ranged across the desert edge long before the border was drawn.

During the 2003-2005 Darfur war and massacres, the most infamous Janjaweed leader was Musa Hilal, chief of the Mahamid.

AFP

AFPAs these fighters proved their bloody efficacy, Mr Bashir formalised them into a paramilitary force called the Border Intelligence Units.

One brigade, active in southern Darfur, included a particularly dynamic young fighter, Mohamed Dagalo, known as "Hemedti" because of his baby-faced looks - Hemedti being a mother's endearing term for "Little Mohamed".

A school dropout turned small-time trader, he was a member of the Mahariya clan of the Rizeigat. Some say that his grandfather was a junior chief when they resided in Chad.

A crucial interlude in Hemedti's career occurred in 2007, when his troops became discontented over the government's failure to pay them.

They felt they had been exploited - sent to the frontline, blamed for atrocities, and then abandoned.

Hemedti and his fighters mutinied, promising to fight Khartoum "until judgement day", and tried to cut a deal with the Darfur rebels.

A documentary shot during this time, called Meet the Janjaweed, shows him recruiting volunteers from Darfur's black African Fur ethnic group into his army, to fight alongside his Arabs, their former enemies.

Although Hemedti's commanders are all from his own Mahariya clan, he has been ready to enlist men of all ethnic groups. On one recent occasion the RSF absorbed a breakaway faction of the rebel Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) - led by Mohamedein Ismail "Orgajor", an ethnic Zaghawa - another Darfur community which had been linked to the rebels.

Consolidating power

Hemedti went back to Khartoum when he was offered a sweet deal: back pay for his troops, ranks for his officers (he became a brigadier general - to the chagrin of army officers who had gone to staff college and climbed the ranks), and a handsome cash payment.

His troops were put under the command of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), at that time organising a proxy war with Chad.

Some of Hemedti's fighters, serving under the banner of the Chadian opposition, fought their way as far as the Chadian capital, N'Djamena, in 2008.

Meanwhile, Hemedti fell out with his former master, Hilal - their feud was to be a feature of Darfur for 10 years. Hilal was a serial mutineer, and Mr Bashir's generals found Hemedti more dependable.

In 2013, a new paramilitary force was formed under Hemedti and called the RSF.

The army chief of staff did not like it - he wanted the money to go to strengthening the regular forces - and Mr Bashir was worried about putting too much power in the hands of NISS, having just fired its director for allegedly conspiring against him.

So the RSF was made answerable to Mr Bashir himself - the president gave Hemedti the nickname "Himayti", meaning "My Protector".

Training camps were set up near the capital, Khartoum. Hundreds of Land Cruiser pick-up trucks were imported and fitted out with machine guns.

RSF troops fought against rebels in South Kordofan - they were undisciplined and did not do well - and against rebels in Darfur, where they did better.

Gold rush

Hemedti's rivalry with Hilal intensified when gold was discovered at Jebel Amir in North Darfur state in 2012.

Coming at just the moment when Sudan was facing an economic crisis because South Sudan had broken away, taking with it 75% of the country's oil, this seemed like a godsend.

AFP

AFPBut it was more of a curse. Tens of thousands of young men flocked to a remote corner of Darfur in a latter-day gold rush to try their luck in shallow mines with rudimentary equipment.

Some struck gold and became rich, others were crushed in collapsing shafts or poisoned by the mercury and arsenic used to process the nuggets.

You may also be interested in:

Hilal's militiamen forcibly took over the area, killing more than 800 people from the local Beni Hussein ethnic group, and began to get rich by mining and selling the gold.

Some gold was sold to the government, which paid above the market price in Sudanese money because it was so desperate to get its hands on gold that it could sell on in Dubai for hard currency.

Meanwhile some gold was smuggled across the border to Chad, where it was profitably exchanged in a racket involving buying stolen vehicles and smuggling them back into Sudan.

Reuters

ReutersIn the desert markets of Tibesti in northern Chad, a 1.5kg (3.3lb) of unwrought gold was bartered for a 2015 model Land Cruiser, probably stolen from an aid agency in Darfur, which was then driven back to Darfur, fitted out with hand-painted licence plates and resold.

By 2017, gold sales accounted for 40% of Sudan's exports. And Hemedti was keen to control them.

He already owned some mines and had set up a trading company known as al-Junaid. But when Hilal challenged Mr Bashir one more time, denying the government access to Jebel Amir's mines, Hemedti's RSF went on the counter-attack.

In November 2017, his forces arrested Hilal, and the RSF took over Sudan's most lucrative gold mines.

Regional muscle

Hemedti overnight became the country's biggest gold trader and - by controlling the border with Chad and Libya - its biggest border guard. Hilal remains in prison.

Under the Khartoum Process, the European Union funded the Sudanese government to control migration across the Sahara to Libya.

Although the EU consistently denies it, many Sudanese believe that this gave license to the RSF to police the border, extracting bribes, levies and ransoms - and doing its share of trafficking too.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDubai is the destination for almost all of Sudan's gold, official or smuggled. But Hemedti's contacts with the UAE soon became more than just commercial.

In 2015, the Sudanese government agreed to send a battalion of regular forces to serve with the Saudi-Emirati coalition forces in Yemen - its commander was Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, now chair of the ruling Transitional Military Council.

But a few months later, the UAE struck a parallel deal with Hemedti to send a much larger force of RSF fighters, for combat in south Yemen and along the Tahama plain - which includes the port city of Hudaydah, the scene of fierce fighting last year.

Hemedti also provided units to help guard the Saudi Arabian border with Yemen.

By this time, the RSF's strength had grown tenfold. Its command structure didn't change: all are Darfurian Arabs, its generals sharing the Dagalo name.

With 70,000 men and more than 10,000 armed pick-up trucks, the RSF became Sudan's de facto infantry, the one force capable of controlling the streets of the capital, Khartoum, and other cities.

Cash handouts and PR polish

Through gold and officially sanctioned mercenary activity, Hemedti came to control Sudan's largest "political budget" - money that can be spent on private security, or any activity, without needing to give an account.

Run by his relatives, the Al-Junaid company had become a vast conglomerate covering investment, mining, transport, car rental, and iron and steel.

By the time Mr Bashir was ousted in April, Hemedti was one of the richest men in Sudan - probably with more ready cash than any other politician - and was at the centre of a web of patronage, secret security deals, and political payoffs. It is no surprise that he moved swiftly to take the place of his fallen patron.

Hemedti has moved fast, politically and commercially.

Every week he is seen in the news, handing cash to the police to get them back on the streets, to electric workers to restore services, or to teachers to have them return to the classrooms. He handed out cars to tribal chiefs.

As the UN-African Union peacekeeping force drew down in Darfur, the RSF took over their camps - until the UN put a halt to the withdrawal.

Hemedti says he has increased his RSF contingent in Yemen and has despatched a brigade to Libya to fight alongside the rogue general Khalifa Haftar, presumably on the UAE payroll, but also thereby currying favour with Egypt which also backs Gen Haftar's self-styled Libyan National Army.

Hemedti has also signed a deal with a Canadian public relations firm to polish his image and gain him political access in Russia and the US.

Hemedti and the RSF are in some ways familiar figures from the history of the Nile Valley. In the 19th Century, mercenary freebooters ranged across what are now Sudan, South Sudan, Chad, and the Central African Republic, publicly swearing allegiance to the Khedive of Egypt but also setting up and ruling their own private empires.

Yet in other ways Hemedti is a wholly 21st Century phenomenon: a military-political entrepreneur, whose paramilitary business empire transgresses territorial and legal boundaries.

Today, this semi-lettered market trader and militiaman is more powerful than any army general or civilian leader in Sudan. The political marketplace he commands is more dynamic than any fragile institutions of civilian government.

Alex de Waal is the executive director of the World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.