Notre-Dame: How an underwater forest in Ghana could help rebuild a Paris icon

Reuters

ReutersWood from a vast underwater forest in Ghana could be used to rebuild Notre-Dame Cathedral after its spire and roof were consumed by a blaze in April.

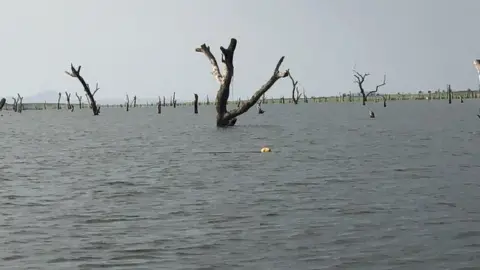

Massive tropical trees have been submerged beneath Lake Volta since 1965, when the construction of Ghana's Akosombo Dam flooded part of the Volta River Basin.

A Ghanaian company, which has government concessions to harvest this wood, believes that using it to rebuild Notre-Dame is more environmentally friendly than cutting down new trees.

Dennis Ivers

Dennis IversKete Krachi Timber Recovery argues that the wood is "much stronger" because it has been preserved from decay by the lake's bog-like conditions, and has started to fossilise.

While some experts have described the proposal as a "genius solution", others warn that it could have disastrous consequences for the ecosystem.

The company has submitted its proposal to the French government, arguing that using wood from Lake Volta would help restore Notre-Dame to its original state.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn estimated 1,300 trees, mainly oaks, were felled in the 12th Century to build Notre-Dame's iconic frame and spire. The deforested area spanned 52 acres - the equivalent of 26 football pitches.

According to Bertrand de Feydeau, vice-president of French preservation group Fondation du Patrimoine, France no longer has giant oak trees of the same size and maturity that were used to build the original structure.

Francis Kalitsi, chairman and co-founder of Kete Krachi, agrees. "We don't think they still have oak in these volumes for the construction of cathedrals," he said.

"Whereas underneath the lake, you have typical African hardwoods that are similar to oak trees - their density may range from 650kg to 900kg per cubic metre. They are structural timbers which could be useful in the reconstruction."

Kete Krachi already harvests the underwater timber using remotely operated machinery guided by video, sonar and GPS navigation. Most of the wood is exported to Europe, and some to South Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Jacob Tetteh Ageke

Jacob Tetteh AgekeThe company says if commissioned, it would sell $50m (£39.5m) worth of wood to the French government. Its proposal has already been acknowledged by the ministry of culture.

Jérémie Patrier-Leitus from the French culture ministry told the BBC: "Right now we don't know if the frame will be rebuilt in wood. We are in the process of securing the monument, and then we will have to rebuild the vault and the spire.

"Reconstruction will start once the structure of the monument is stabilised and preserved. We will study the different generous offers once we have confirmed the material used to rebuild the frame."

Notre-Dame before the fire in 360° video

Bog oak: A more durable wood

Dr Cathy Oakes, specialist in French and English medieval architecture and iconography at the University of Oxford, said the wood in Lake Volta could be similar to "bog oak", which was widely used in medieval constructions and furniture, although not in the original Notre-Dame.

"Bog oak has similarly been exposed to water for a long period of time, so it's stronger and more durable," she said in remarks before her death this summer.

Dennis Ivers

Dennis IversThe shortage of oxygen, and the acidic conditions of peat bogs and riverbeds help to preserve tree trunks from decay. The wood then begins to fossilise, making it significantly stronger.

Andrew Waugh, director of London-based sustainable architecture practice Waugh Thistleton Architects, said using African wood such as iroko from Lake Volta could be a "genius solution".

"It would seem to be a great way of solving a problem and helping a poorer economy," he said.

Dennis Ivers

Dennis Ivers"Iroko is an incredibly durable, hard-wearing timber. It's very stable. Unless there are any issues with decay from taking it out of the water, one would imagine it would be a great timber to work with."

But what about the environment?

However, concerns have been raised about the possible negative impact harvesting wood from Lake Volta could have on the local ecosystem.

A report in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives said pulling trees from lake beds can pollute the water with sediment, thereby blocking the light needed by aquatic organisms to survive.

Dennis Ivers

Dennis IversThe trees also provide a habitat for fish and other wildlife. Cutting them could disrupt the lake's ecology, thereby threatening Ghana's fishery industry - a lifeline for an estimated 300,000 fishing families.

Stephen Anani, a project officer at local NGO Friends of the Nation, told the BBC that removing underwater trees had led to a "sharp decline" in the number of fish in Lake Volta because they tend to breed around stumps.

"It's destroying the habitat where fish lay their eggs," he said. "Some of the fish are now endangered. If you speak to fishermen along the lake, they complain bitterly."

Kete Krachi Timber maintains that it does not uproot trees, but cuts above the buttress, leaving a portion of the stem and all the roots intact. It says this "minimises" ecological disruption.

Questions have also been raised about the carbon footprint associated with extracting the wood and transporting it from Ghana to France.

Dennis Ivers

Dennis IversAccording to the International Maritime Organization's third Greenhouse Gas study, maritime transport emits around 940 million tonnes of carbon dioxide every year and accounts for about 2.5% of global greenhouse gases.

Dr John Recha, a Nairobi-based climate scientist at the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, says harvesting the wood and transporting it to France could leave a "significant" carbon footprint.

"A ship typically uses a lot of fuel," he told the BBC. "The machinery used on seas, oceans and lakes are also typically more complex and require more fossil fuels, which emit carbon into the atmosphere."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKete Krachi maintains, however, that emission levels related to salvaging timber from the lake are "much lower" compared to emissions from cutting trees on land.

"The bulk of fuel consumption in felling trees is in log transport - and water transport is more energy efficient than land transport," Mr Kalitsi said.

Dr Tristan Smith, an energy and shipping expert at University College London's Energy Institute, agrees that ocean shipping is normally considered the most efficient mode of transport in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

Jacob Tetteh Ageke

Jacob Tetteh AgekeHowever, he warned that pollution from shipping has not been as tightly regulated as other industries, so the plan to ship wood may not be as eco-friendly as might be assumed.

"Depending on the specifics of the route taken and the ships used, the greenhouse gas emissions from the sea voyage may be of a similar magnitude to that from the trucking used at either end of the voyage," Dr Smith said.

Kete Krachi says the ships it plans to use would be travelling to France anyway on established trade routes, so it would contribute a "negligible" quantity of additional carbon into the atmosphere.

Dennis Ivers

Dennis IversThe company ultimately believes its potential involvement in rebuilding Notre-Dame would not only benefit Ghana's economy, but have a wider symbolic importance.

"It would mean we could play a role in an architectural feat that is a gift not only to France, but to the world," Mr Kalitsi says.

Dr Oakes agrees.

"In the end, it's got to come down to practicalities of experience. But to think that the world is being invited to contribute towards the reconstruction of this building is great."