How Benin's democratic crown has slipped

AFP

AFP

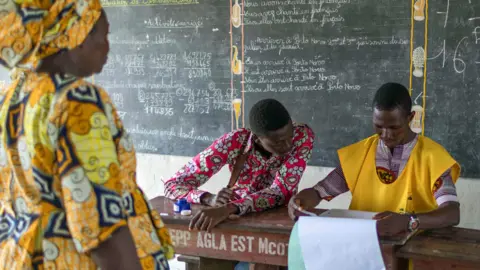

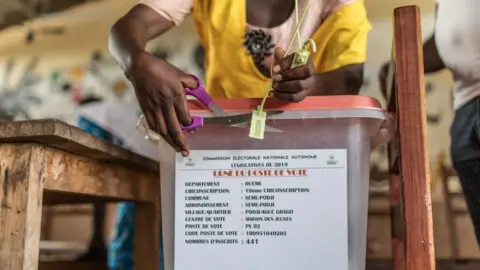

The small West African country of Benin was in the vanguard of a new wave of multiparty democracy that spread across the continent from 1991 onwards. But Benin's most recent elections have tarnished its image, analysts say, after the opposition were barred, and the military opened fire on protesters.

What happened?

The army is still patrolling the streets of Benin's main city, Cotonou, days after deadly force was used against protesters who had gathered close to the home of opposition leader and former President Thomas Boni Yayi.

No official death toll has been given but the opposition says seven civilians were killed.

Their anger was sparked by the exclusion of all opposition parties from parliamentary elections on 28 April. Turnout was at a record low, at only 27%.

Internet access was restricted on the day of the polls, a move that rights groups and civil society organisations roundly condemned.

"A blunt violation of freedom of expression," is what Amnesty International called it, adding it showed an "alarming level of repression".

"This situation did not start with the elections," Adeline Van Houtte of the Economist Intelligence Unit told the BBC. "Over past year we have seen the constraining of civil liberties and crackdowns on protests."

"Democracy has been planted in minds of citizens and has been for a long time, so this was a final blow. It has ruined Benin's image at the national and international level."

What does it mean for democracy in Benin?

After a Marxist-Leninist regime and a series of coups d'etat, Benin along with Zambia became one of the first African countries to introduce multiparty elections in 1991.

Those polls saw Benin's former President Mathieu Kerekou become the first West African leader to admit defeat in an election.

AFP

AFPSince then Benin has been regarded as a democratic model, said the BBC's Rachida Yénoukunmè Houssou in Cotonou, with several African nations replicating its reconciliation body, the National Conference of Active Forces of the Nation.

But new electoral laws introduced this year mean that a political party had to pay about $424,000 (£328,000) to field a list for the 83-seat parliament.

"What's happening doesn't honour the democratic image of Benin," the president, Patrice Talon, admitted on state TV in April.

"This situation brings discredit on our democracy and on me."

Yet the presidency last week dismissed calls from the opposition to invalidate the results and start again - calls which they repeated at the weekend.

Presidential spokesman Wilfried Léandre Houngbedji had labelled their actions "fear-mongering" and said the polls were conducted in line with the law, RFI reports.

Analysts say this is a turning point for Benin.

Gilles Yabi of Dakar-based think-tank Wathi, said Benin was in a "deadlock" that was tarnishing its image.

"We're tipping over into violence," the Beninese analyst said. "It damages the image of the country, where political dialogue meant violence was avoided in the past.

"With high numbers of people not turning out to vote, the National Assembly will lack legitimacy."

It is also likely to see the government "ruling without checks and balances," Ms Van Houtte of the Economist Intelligence Unit said, "opening the way for further weakening of Benin's democratic credentials".

"President Talon will have a free a hand now to pass through the constitutional changes that he has wanted to make over the past two years. Policy-making will be faster but on the other hand his cherished image of a modern president will be damaged."

Why has it come to this?

Five years ago voters in Benin could chose from 20 parties for the 83 seats in parliament, AFP news agency reports.

The number of political parties has since risen to more than 200, which President Patrice Talon has sought to reduce ostensibly as part of a reformist agenda.

MPs loyal to the president initiated two laws to this end - a new electoral code and a new charter for political parties.

AFP

AFPUnder these new terms, all political parties have had to file administrative documents in order to be approved by the Interior Ministry.

Only two parties met the criteria - Republican Bloc and the Progressive Union - both of which are loyal to the president.

All the others were deemed inadmissible and so excluded from the legislative elections.

Opposition figures said it showed that President Talon simply wanted control over parties and institutions.

The African Union observer mission concluded that the "apathy of the Beninese people" was a result of the opposition ban.

US Ambassador Patricia Mahoney said the polls were "neither fully competitive nor inclusive and do not reflect the Benin that we know".

Who are the political rivals?

Former President Thomas Boni Yayi and President Patrice Talon are old friends, said the BBC's reporter in Benin.

Nicknamed the "king of cotton" thanks to the wealth he amassed in that sector, former businessman Mr Talon financed Mr Boni Yayi's successful 2006 and 2011 presidential campaigns.

AFP

AFP

But relations between the two men had soured by the time of President Yayi's second term in office.

First, a corruption scandal saw Mr Talon accused of misappropriating more than 18.2m euros ($20.4m; £15.5m) in 2011, then a year later, the businessman fled to France and was linked to a plot to poison President Yayi.

France resisted an extradition order. But Mr Talon was later pardoned by the president in 2014, paving the way for his return to Benin.

However, Mr Talon harboured political ambitions and their apparent reconciliation didn't last long.

There were fears that Mr Yayi would defy constitutional term limits and stand for a third term in office.

But in the end he didn't, and the 2016 presidential election saw Mr Talon defeat Mr Yayi's preferred candidate Lionel Zinsou.

Now in opposition, Mr Yayi has been at the forefront of the demands to re-run the latest parliamentary elections, along with another former President, Nicéphore Soglo.

What does the future hold?

With the election results validated by the constitutional court, MPs are to be formally sworn in on 15 May.

The opposition maintains that the results should be annulled and the elections re-organised. But so far their calls have been ignored by Mr Talon's government.

"According to the courts in Benin they [the polls] were in conformity with electoral law," said Ms Van Houtte of the the Economist Intelligence Unit.

"That's not something anyone outside the country can do anything about - other than condemn the use of force against protesters and the internet shutdown.

"Anything else would be seen as interference."