How Facebook is being used to profile and kill Kenyan 'gangsters'

.

.A suspected death squad operating inside Kenya's police force is using Facebook to target and kill young men they believe to be gang members, residents of a poor and overcrowded area of the capital have told a public meeting.

"I have lost two husbands in one year," a tearful young woman, balancing a toddler on her side, told the crowded town hall meeting in Nairobi's Kayole residential estate last month.

Others came forward to the microphone to tell similar stories about losing young relatives aged between 15 and 24.

The state prosecutor, top police officers and human rights activists, who were also at the rare gathering, listened as community leaders explain how these youngsters, suspected to be criminals, were profiled within various Facebook groups by "gangster hunters".

"They profile them on Facebook, after one week or a month they shoot them, and put pictures of their dead bodies on Facebook," Wilfred Olal from the Dandora Community Justice Centre told the meeting.

The posted photos, sometimes showing close-up shots of heads split open by bullets and eviscerated bodies, usually come with a warning that the same fate awaits other criminals. Some of the images are blurred by Facebook but a user can choose to un-blur them.

The Kayole residents say there are various Facebook groups, some public and some which are closed, that are updated with gruesome pictures almost every day.

Police tears

Duncan Omanga, a researcher at Moi University in Kenya, who has been monitoring such Facebook pages for three years, says that suspected police officers use anonymous digital personas to spy on their targets.

"The first unofficial police Facebook account appeared under the name Hessy wa Kayole [Hessy from Kayole].

"Hessy became the shadowy crime-hunter, the mystical lone ranger."

With his legend spreading on social media, more Facebook accounts with names of gang hunters from other crime-ridden residential estates started to appear.

According to Mr Omanga, it seemed to be a deliberate strategy to give the impression of "police omnipresence and 'state' surveillance" in these areas of Nairobi.

Last November, former police chief Joseph Boinnet had said: "The person behind the Facebook accounts is not a police officer, but [a civilian] passionate about security matters."

And the police's Director of Criminal Investigations (DCI), George Kinoti, who shed tears whilst listening to some of the testimonies in Kayole, told the meeting that he had no knowledge of agents such as Hessy.

"I am saying no-one will ever cover for a police officer who kills under my watch."

But his comments were drowned out by the crowd, with someone shouting: "They are on Facebook, even on Twitter."

The meeting in Kayole was organised by the director of public prosecutions (DPP) after activists and residents said the police were not taking them seriously.

'Fixing an appointment with God'

Mr Omanga's research has found that in one month, an average of six suspected gangsters are profiled, details of their alleged crimes and areas of operation, and the kind of arms they are believed to own are published on various Facebook accounts and groups.

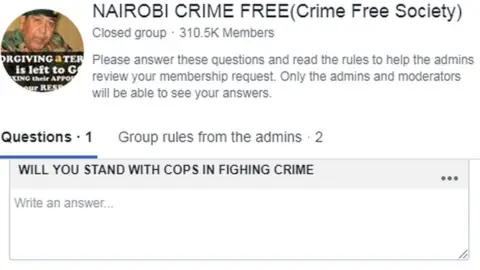

In the same period, between 10 and 12 police killings of suspected gangsters are published on a closed Facebook group called Nairobi Crime Free.

It has more than 300,000 members and has the slogan: "Forgiving a terrorist is left to God, but fixing their appointment with God is our responsibility", along with the logo of an unidentified man wearing army combat uniform and a beret.

Facebook/Nairobi Crime Free

Facebook/Nairobi Crime FreeMr Omanga says the macabre images shared in the group are intended to shock and show bravado. Sometimes an old picture of the victim is juxtaposed beside their dead body.

The group members seem to revel in the content - judging from the likes and the positive emoticons that are left below each post.

Some also share their personal experiences as victims of crime and call on the police to eliminate other criminals.

To sign up for this front-row digital seat, new users have to answer three questions, including whether they support police's efforts to fight crime.

Criminals also pay attention to these Facebook pages just in case they are listed for elimination.

After being profiled, several young men have gone into hiding or have sought protection from human rights organisations.

Mr Omanga says the police were also able to learn about some gangs through Facebook when members used their personal accounts to show off their exploits and even taunt officers.

'Gaza gang wiped out'

But this has largely stopped since one gang leader, Mwani Sparta, notorious for posting about his ostentatious lifestyle, uploaded of a photo of himself in 2017 brandishing a machine gun along with his notorious accomplices.

Facebook/Mwani Sparta

Facebook/Mwani Sparta

He realised his mistake and took it down - but it had already been shared and the police gained an invaluable insight into the identity of the Gaza gang members.

All became suspected targets of extrajudicial killings. Each time a Gaza gang member died, the group photo would appear on Facebook with another of the faces struck out, Mr Omanga said.

Another gang member, whose photo had also been shared, seemed so terrified by the killings that he posted on Facebook that he had given up the criminal life and become a born-again Christian - and was subsequently arrested.

But it is not just criminal gangs who are the targets from these Facebook groups. Human rights activists say they also feel under threat for speaking out about extrajudicial killings.

"We have also been profiled on these Facebook pages - pictures of our offices have been posted. We have reported to the police but nothing has been done," Mr Olal said, adding that they also feel harassed by the police as activists are sometimes arrested but then not charged.

"We want to know if these people, like Hessy, are police officers and if they are, do they have a right to shoot people dead and post pictures of their dead bodies on Facebook?"

Graphic content 'banned'

An umbrella group, called Uhai Wetu, has been now been formed so human rights activists from different suburbs can support each other in forming a joint response to these threats.

They have repeatedly asked Facebook to take down the offending content, which they say goes against the platform's community standards, but despite several attempts they have not been successful, a researcher with the organisation told the BBC.

You may also be interested in:

"We recognise that we have a responsibility to fight abuse on our platform and we are working hard with partners on the ground, including civil society organisations, to better understand local issues and tackle them more effectively," a Facebook spokesperson told the BBC.

The spokesperson said that Facebook had clear rules against posting graphic and violent content and "when we are made aware of this content, we remove it".

"Our investigation into this issue is ongoing and we thank the BBC for bringing it to our attention," Facebook added.

However, there has not been a general outcry about these killings, except from the affected communities.

International Justice Mission

International Justice MissionMr Omanga says a no-nonsense, gung-ho police officer has an enduring appeal for many Kenyans fed up with what they see as a justice system that is corrupt and slow.

An article in the Kenyan press a few years ago about four of Nairobi's "super cops" said they had earned themselves "the licence to kill", the researcher said.

"The writer said they were 'cut from the same cloth as the legendary Patrick Shaw,'" he said, explaining that this was a reference to a British settler who had served as a volunteer policeman after Kenya became independent in 1963 and was heralded as a model for dispensing "on the spot justice".

For Mr Olal, who admits that crime is a big problem in some of the Nairobi residential estates, says it is a question of the law being applied equally.

"If rich people suspected of stealing taxes are being taken to court, then we also want our young men to have a fair hearing," he said.