Letter from Africa: How Nigeria's elite avoid 'bad education'

Getty Images

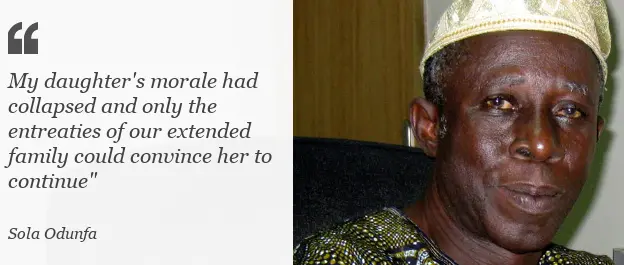

Getty ImagesIn our series of letters from African writers, journalist Sola Odunfa reflects on a controversial proposal to ban the children of government officials and top civil servants from completing their education abroad.

Back in the 1980s, my daughter won a place at the Obafemi Awolowo University, one of the top state-funded institutions in Nigeria.

She embarked on her studies with a spring in her step, expecting to emerge with a prestigious qualification five years later.

Soon enough though, she would learn the truth behind the modern Nigerian saying: university students can only be sure of their matriculation date; they cannot say when they will graduate.

Her studies seemed to take forever. If the lecturers were not on strike, they were planning to go on strike. One of the strikes - a nationwide action - lasted almost a year.

Halfway through the course, my daughter's morale had collapsed and only the combined entreaties of our extended family could convince her to continue her education.

Disillusioned and frustrated, she eventually graduated. The five-year-course was completed in seven, through no fault of her own.

More from Sola Odunfa:

If that sounds bad, things are even worse now.

Universities remain poorly funded and the lecturers' union - known by its acronym ASUU - is more militant than ever, routinely threatening to close down universities in its battles with the government.

It is today widely regarded as the most strike-prone of Nigeria's labour unions. It says the government rarely delivers on its promises.

As well as looking out for its members' interests, the ASUU pushes for the government to increase investment in higher education.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRecently, some parliamentarians came up with a proposal that, they said, would do exactly that.

They proposed a ban on the children of top officials from travelling abroad to complete their studies.

They argued that this would compel government officials - many of whom send their children to foreign universities - to increase funding for the domestic education sector.

'Climate of decay'

According to the lawmaker behind the proposal, some 75,000 Nigerians are currently studying in countries such as Ghana, Benin Republic, Egypt, the UK and US - a form of educational tourism that represents a loss of N1tn ($2.7bn; £2.1bn) to the economy.

It is in this climate of decay that private universities have been flourishing in Nigeria.

Having outlawed teaching unions, these institutions can guarantee a stable academic calendar.

But their fees tend to be very high, and so the young Nigerians going to study abroad include not just the offspring of elites but also those whose parents want to avoid the state system but cannot afford a private education at home.

For them, the foreign option can be more economical, especially if their children take part-time jobs to offset the cost.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe proposed ban did not get very far in parliament.

The debate on the topic was suspended after the speaker ruled that it would contravene individuals' right to free movement.

And so, Nigerians continue to send their children to study abroad.

Meanwhile, the country's lecturers are back on strike - complaining about the lack of funding for universities.

More Letters from Africa

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica