A guide to Africa's 'looted treasures'

During colonial rule in Africa, thousands of cultural artefacts were plundered. African countries want them back and major museums across Europe have agreed to loan the famous Benin Bronzes back to Nigeria. Now France has launched a report calling for thousands of African art in its museums to be returned to the continent.

Benin Bronzes

British Museum

British MuseumThe Benin Bronzes, which are actually made of brass, are a collection of delicately made sculptures and plaques that adorned the royal palace of the Oba, Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, in the Kingdom of Benin, which was incorporated into British-ruled Nigeria.

They were carved out of ivory, brass, ceramic and wood.

Many of the pieces were cast for the ancestral altars of past kings and queen mothers.

In 1897, the British launched a punitive expedition against Benin, in response to an attack on a British diplomatic expedition.

Apart from bronze sculptures and plaques, innumerable royal objects were taken as a result of the mission and are scattered all over the world.

AFP

AFPThe British Museum in London says many of the objects from Benin in its collection were given to it in 1898 by the Foreign Office and the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

In October, top museums in Europe agreed to loan crucial artefacts back to Nigeria for the new Royal Museum, which it plans to open in 2021.

Man-eaters of Tsavo

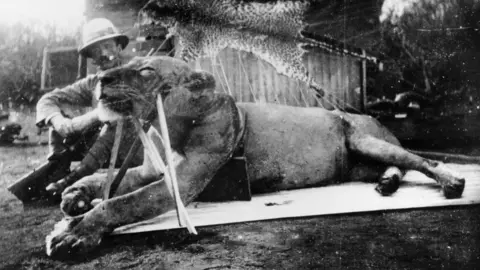

Field Museum of Natural History

Field Museum of Natural HistoryThese were two infamous lions from the Tsavo region in Kenya, East Africa that killed and ate railway workers on the British Kenya-Uganda at the end of the 19th Century.

The labourers were building the railway line between Mombasa and Lake Victoria over nine months in 1898.

Field Museum of Natural History

Field Museum of Natural HistoryThe two killer beasts were eventually shot dead by British engineer Lieutenant Colonel John Patterson, at the helm of the railway project.

The stuffed lions were purchased from Patterson by the Field Museum of Natural History in the US city of Chicago in 1925 and catalogued into the museum's permanent collections.

Lt Col Patterson reported the lions' feeding frenzy took the lives of 135 railway workers and black Africans, but the Field Museum says later research conducted by its scientists drastically reduced that estimate to 35.

The Kenya National Museum wants the lions returned.

Rosetta Stone

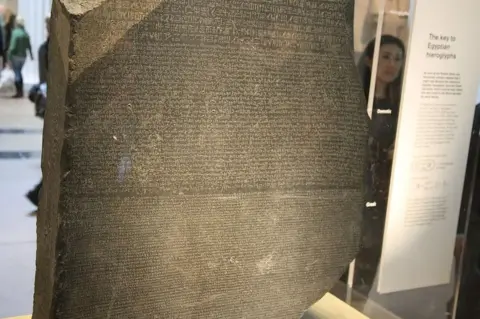

AFP

AFPThe 1.12m (3ft 6in) high Rosetta Stone in the British Museum is originally from Egypt and is a stele made out of granodiorite, which is a coarse-grained rock.

It is a broken part of a bigger slab with text carved on to it that has helped researchers learn how to read Egyptian hieroglyphs - a form of writing that used pictures as signs.

It features three columns of the same inscription in three languages: Greek, hieroglyphs and demotic Egyptian - and is the text of a decree written by priests in 196 BC, during the reign of pharaoh Ptolemy V.

It is unclear how the stone was discovered in July 1799, but there's a general belief that it was found by soldiers fighting with the French military leader Napoleon Bonaparte as they were building an extension to a fort near the town of Rashid - also known as Rosetta - in the Nile Delta.

When Napoleon was defeated, the British took possession of the stone under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801.

It was then transported to England, arriving in Portsmouth in February 1802. George III offered it to the British Museum a few months later.

Bangwa Queen

Dapper Foundation

Dapper FoundationThe 32in (81cm) tall Bangwa Queen is a wooden carving from Cameroon, representing the power and health of the Bangwa people.

It is one of the world's most famous pieces of African art and has huge sacred significance for Cameroonians.

Sculptures were made of titled royal wives or princesses and would be referred to as Bangwa Queens in the Bangwa land of present-day Lebialem district of Cameroon's South-West region.

The Bangwa Queen was either given to or looted by the German colonial agent Gustav Conrau in around 1899 before the territory was colonised.

It ended up in the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin and was then bought by an art collector in 1926.

According to the New York Times, US art collector Harry A Franklin bought the carving in 1966 for $29,000 and after his death it sold at a Sotheby's auction for $3.4m.

Surrealist portrait photographer Man Ray also included the Queen of Bangwa in a 1937 portrait of a nude model - in what the New York Times says became one of his famous images.

The Dapper Foundation in Paris, France now owns the Bangwa Queen sculpture - and it was on display at the Musée Dapper until 2017 when the museum that focused on African art closed because of low attendance and high maintenance costs.

Traditional leaders of the Bangwa have been corresponding with the foundation, requesting its return to Cameroon.

Authors of the report commissioned by President Macron, Senegalese writer and economist Felwine Sarr and French Historian Bénédicte Savoy, have recommended that French law is changed to allow the return of the African art.

Maqdala treasures

V&A Museum

V&A Museum

The Maqdala treasures include an 18th Century gold crown and a royal wedding dress, taken from Ethiopia (formerly Abyssinia) by the British army in 1868.

Historians say 15 elephants and 200 mules were needed to cart away all the loot from Maqdala, Emperor Tewodros II's northern citadel capital.

The British raided Maqdala in protest at the detention of its consul when relations between the two powers deteriorated.

V&A Museum

V&A MuseumThe crown, admired for its silver and copper filigree designs and religious embossed images, and royal wedding dress are significant symbols of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Scholars believe the crown was commissioned in the 1740s by Empress Mentewwab and her son King Iyyasu and given as a gift to a church in Gondar, together with a solid gold chalice.

The dress and jewellery belonged to Emperor Tewodros II's widow, Queen Woyzaro Terunesh.

Ethiopia lodged a claim in 2007 for the return of the antiquities. In April this year, the V&A offered to return the treasures to Ethiopia on loan.

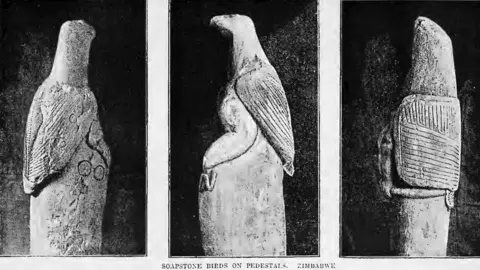

Zimbabwe bird

WikiCommons

WikiCommonsA soapstone sculpture of a fish eagle is Zimbabwe's main national emblem. Eight of the Zimbabwe Birds were looted from the ruins of an ancient city.

Only eight of the birds were ever recovered. They stood on the walls and monoliths of the ancient city built between the 12th and 15th Centuries by the ancestors of the Shona people.

Seven of the carvings are in Zimbabwe since 2003 when the bottom section of one was returned by Germany.

It had ended up in the hands of a German missionary who sold it to the Ethnological Museum in Berlin in 1907.

Then after Soviet troops invaded Germany at the end of the World War Two, it was moved from Berlin to Leningrad and remained there to the end of the Cold War and then returned to Germany.

The eighth remains in the old bedroom of 19th Century British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, whose home in the South African city of Cape Town is now a museum.

He had taken a number of birds from Great Zimbabwe to South Africa in 1906. South Africa returned four of them in 1981, a year after Zimbabwe gained its independence.

How much can you remember?