Ukraine tension: Could conflict escalate to war, and other questions

Getty Images

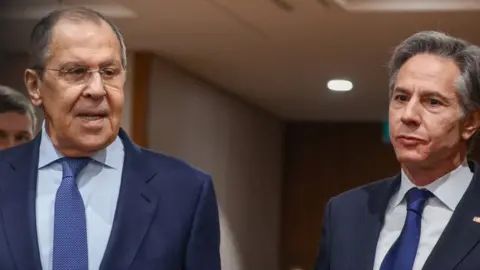

Getty ImagesRussia and the US have held "frank" talks as fears mount of a Russian military offensive against Ukraine.

An estimated 100,000 Russian troops have been deployed near Ukraine, although Russia denies it has any plans to invade.

The US and its allies have threatened new sanctions, but the two sides have agreed to keep talking.

As the situation intensifies, two of the BBC's most senior journalists on the region answer your questions.

- Paul Adams is the BBC's international affairs correspondent and has just returned from Ukraine. He has reported from conflict zones and negotiating rooms from across the world for more than three decades

- Steve Rosenberg is our Moscow correspondent and expert on all things Russia. He has lived and worked there since the end of the Cold War and has reported across the breadth of the country for the BBC

1. Are the countries around Ukraine safe from a bigger war? - Hristo, Bulgaria

Paul Adams writes:

There's no war, yet, and hopefully conflict can be avoided. The diplomats are still talking.

But, yes, it's not only Ukraine that's worried about the possibility of war.

Other countries in the region - like the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia - are concerned that any future conflict could spread to their countries.

2. In the event of an invasion, how likely are civilian casualties? - Danil Gorbununov, Ukraine

Paul Adams writes:

This could play out in any number of ways, from so-called "hybrid" attacks - hacking, disinformation, etc - all the way up to a full-scale invasion, the likes of which Europe has not seen since World War Two.

One way or another, civilians will be caught up in it. They might find themselves freezing in their homes as the power grid collapses, or trapped behind Russian lines if, as some have speculated, Russian tanks move in from the territory of neighbouring Belarus (personally I find this unlikely, but Russia seems happy to keep everyone guessing).

This conflict has already claimed around 14,000 Ukrainian lives. If Russia tries to take more territory or install a more friendly regime in Kyiv, it's hard to see how this won't result in many, many casualties.

EPA

EPA3. Why does Russia fear Nato? - Mike Hancock, US

Steve Rosenberg writes:

I don't believe Russian officials really fear Nato, which is a defensive alliance.

According to the US Secretary of State, only 6% of Russia's borders touch Nato countries. Is that a threat to Russian national security?

Also, many Nato countries actually have good relations with Moscow, and Russia even sells weapon systems to Turkey, a Nato member.

I think this is more about the Kremlin trying to carve out a sphere of influence for itself on its doorstep - and using Nato as an excuse to do that.

4. Would this story be very different if Ukraine was already a Nato member? - Ryan Johnston, Belfast, Northern Ireland

Paul Adams writes:

Ukraine (and Georgia) have been on a theoretical path to Nato membership since a summit in Bucharest in 2008. But it's a long and rocky path.

Since 2014, when Ukrainians got rid of a president they thought was going to side with Russia rather than Europe, the country has been at war with Russia.

First Russia took over Crimea. Then it encouraged pro-Russian separatists in the south-east of the country (the area called the Donbas).

Nato can't welcome members who are already involved in conflicts of this kind. There are also all sorts of other things Ukraine needs to do, in terms of political reforms and improving their military.

Right now, to welcome Ukraine into Nato would be seen as the ultimate red rag to a Russian bull. So no-one thinks it's going to happen any time soon.

In many ways, this is a red herring, as President Putin knows perfectly well that membership is not around the corner.

Tensions over Ukraine

- EXPLAINED: Is Russia preparing to invade Ukraine?

- FROM KYIV: Ukrainians wait as Russia faces off with the West

- FROM BRUSSELS: EU 'closest to war' in decades over Russia-Ukraine crisis

- UK SUPPORT: UK says it is sending weapons to defend Ukraine

5. If Putin says he won't invade Ukraine, why is the US warning Russia? - Assad Ullah, China

Paul Adams writes:

Words are one thing (and you're right - the Russians keep saying they won't invade), but their actions point in another direction.

There has been the massing of forces, the support for separatists in the Donbas (including handing out around one million Russian passports), and the threat of dire consequences if Ukraine does anything provocative (which, until now, it sensibly hasn't).

Plus, President Putin's rejection of Ukraine's independent identity is not a secret - he wrote a long essay on the subject last year. You can read it online, but be prepared for a deep dive into ancient Russian history.

6. What is Putin's justification for so many troops on the border? - Richard Sullivan, Gloucestershire, UK

Steve Rosenberg writes:

Basically, Russia's position is: "Hey, this is our country: we can move our troops wherever we want to on our territory."

The result - an estimated 100,000 Russian soldiers near its border with Ukraine, plus more Russian troops arriving in Belarus for snap war games.

A potential invasion force, says the West. Moscow denies it.

7. Why are the superpowers interested in Ukraine? Ernest Onyameamah, Ghana

Paul Adams writes:

For Russia, it's all about recreating something that was lost with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 - a Russian sphere of influence.

People also ignore how humiliated some Russians felt by the end of the Soviet empire and the West's eager expansion into eastern Europe. It left deep scars.

For the US, it's about defending the principle that countries have the right to choose their own destiny, alliances and future paths.

Not just Ukraine, but all those former members of the old Warsaw Pact (a Soviet-led military alliance during the Cold War) who turned to Nato in the 1990s.

It's also about trying, as much as it can, to limit what the West sees as Vladimir Putin's malign influence.

8. What could Russia do to Europe's gas supplies? - George

Steve Rosenberg writes:

Could Russia choke off gas supplies if the West hits Russia with sanctions in the event of an invasion?

It's a possibility. Russia likes to portray itself as a reliable energy supplier. But in a sanctions war, the energy gloves might come off.

The EU relies on Russia for 40% of its gas. So any supply reduction or cuts by Russia would be felt acutely in Europe.

True, Russia would lose out financially, too. But the Russians think they have an alternative market - China - and are already looking to boost energy supplies there.

Reuters

Reuters9. How are people in Ukraine feeling?

Paul Adams writes:

I was in Kyiv last week and I found a mixture of apprehension and resignation. As President Zelensky says, "what's new here?" - Ukraine and Russia have been at loggerheads for eight years.

War is already a reality, even if the conflict in the Donbas is now a frozen, low-level confrontation. I didn't detect any panic in Kyiv, but people did seem to believe that one day, unless he's stopped, Vladimir Putin will try to do something.

They know where their bomb shelters are and some say they're willing to volunteer in one way or another if war breaks out. But they're really tired of the conflict and have no appetite for a fight which they know they would probably lose.

10. Is Russia preparing to invade Ukraine?

Paul Adams writes:

The only honest answer any of us can give right now is that we have absolutely no idea. Russia has certainly assembled enough men and equipment to do something in Ukraine. Not enough (by a mile) for a full scale invasion, but enough, perhaps, to mount a more limited operation - perhaps in the Donbas.

But Russians are not clamouring for war and Putin knows that "victory" in Ukraine could kill an awful lot of his own soldiers.

Does his visceral distaste for the very idea of Ukraine trump all other rational considerations? Surely not. But he's caught the West's attention and he has a long list of demands which go way beyond the question of Ukraine and Nato (particularly as he knows Ukraine is not about to join).

So he will continue to hold a figurative gun against Ukraine's head while he pursues his wider agenda. And as any film buff will tell you, when there's a gun on the table, it usually means someone's going to use it later.