Pride month: Five stories from around the world

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesIn many major cities around the world, Pride has gone mainstream. Municipal mayors march alongside drag queens, and international brands from Nike to Coca Cola fly the rainbow flag to show their support.

But in other places, Pride is still celebrated in secret, as LGBT people struggle to have their rights recognised and face threats of violence.

The BBC spoke to five members of the LGBT community from different countries about what Pride means to them where they are.

Ziva Gorani, Canada

'A lot of the younger generations of queer people are born into Pride'

Pride is a fight that can't stop. It's solidarity.

From the perspective of a newcomer, who moved to Canada from Syria in 2016, it has a more heightened meaning.

Me and my friend wanted to start a digital Pride in Syria, but it was too dangerous.

I was in Turkey as a humanitarian worker for two years before coming here. I was starting my transition, and it was clear that I was going to be in a situation where it was so dangerous, so I sought refuge here.

Ziva Gorani

Ziva GoraniIn Canada, with capitalism, Pride has been hijacked by those companies. Toronto Pride is one of the largest prides in the world, and receives a lot of funding from the city and from corporate sponsors.

A lot of the younger generations of queer people are born into Pride. But people of the same age who came here from elsewhere, they know that the right to walk in the street with colours and rainbows is something they've earned, something they've fought so hard for. It's not to be taken for granted.

Pride here is functioning in a silo of queer rights that doesn't always involve trans rights and doesn't involve intersectional rights. In 2016, Black Lives Matter interrupted the Toronto Pride parade to protest police marching in the parade.

It was a huge issue - a lot of the gay white community second-guessed the Black Lives Matter movement.

There's this idea that one right can exist in separation from another and it doesn't. You can't stand for one right, and not stand in solidarity for other rights.

It's so tempting to come out and look at Pride and say what a spectacle, with all that capitalism and all that merchandise. But to be fair, that's very subjective and biased from my point of view. From the point of view of a lot of people, it's meaningful.

But wherever there is Pride there is radicalisation. There is affirmation. It brings that sense of community to a new level.

I'm most happy for non-binary folks, for trans folks, for newcomers, who have so little space in real life that they can have a bigger space of expression during Pride.

Piotr Jankowski, Poland

'The biggest idea about Pride is about hope'

We didn't have Pride last year. That's why all of our community was hungry for Pride.

There were some homophobic incidents - I know it maybe sounds strange, but we're used to it. It's our every day and our reality and so we don't pay it too much attention and focus on Pride as a celebration.

In 2019, there were violent attacks against Pride in Bialystok. I had friends who were there, some of them were hurt, some had broken arms. After Bialystok, that's when I decided to fully commit myself to activism.

Piotr Jankowski

Piotr JankowskiWhen the right-wing party started a campaign of hatred, people from our community decided to organise more and more Prides. We cannot wait for our country, our government. They say LGBT people are not a people, we are just an ideology. Living in a country where we are dehumanised, we have to find ways to help each other and support us and fight for our rights.

Coming out at 27 was probably the most dramatic decision in my whole life. Not only because I had to come out for my family or my friends, but for myself. Because homophobia is an everyday experience, I really thought I was some kind of pervert, some kind of sick person, and I didn't accept that.

But I could do this, or suicide. Suicidal thoughts are common in Poland - about 70% of LGBT teenagers have suicidal thoughts.

Looking back, it was the best decision in my whole life. And second-best decision was to go to Tolerado, an LGBT advocacy organisation, and to start working there.

I love the fact that I can help people. I answer the phone from mothers of transgender teenagers who just came out - and because there is no official education about it, they don't know what to do. They are coming to Tolerado saying 'please help us, my kid is transgender, what should I do? How can I support them? Is it normal?' At the end of the day when they come to us and have contact information for a specialist, they are grateful.

I believe. I have faith, it's not reality, that it will get better. Baby steps. But we have to keep in mind that it's thin ice.

Some towns have created "LGBT-free zones" - these local politicians are not in the shadow with their homophobia, they're in full sun.

Politicians in big cities might be more tolerant - but they say 'let's talk about gay rights in 10 years, 20 years, let's wait for it'.

I was waiting for Warsaw Pride for more than a year because of Covid, and in these last few weeks before Pride, I was waiting for it almost like for Christmas or Hanukkah. It's a festival. But with Pride we are connected to our fight for our rights.

The biggest idea about Pride is about hope. We've got hope for all of society, for our community, and I hope someday, we can go into retirement and say 'everything is done'.

Atilio Deana, Uruguay

'A lot of people in the community are conscious of the fragility of our rights'

In Uruguay, what we call Diversity Pride usually takes place in September, because that is our spring season in the southern hemisphere. June (when many Pride parades take place around the world) is our winter.

In the early 1990s, when Uruguay started celebrating Pride, I was living in France, but when I came back from France in 1993 I started participating.

Atilio Deana

Atilio DeanaThe Paris parade was like a festival, like in New York. A lot of people in the street, very open, a lot of visibility from the LGBT community. When I came to Uruguay it was very weird - a lot of people were using masks to hide their faces. Very few people, less than 100 people, parading.

Now it's completely different. The young people took over the festivities. It's a reason to go out and dance and have fun.

For a little country like us, with 3.5 million people, it gathers about 150,000 people. It's a big parade - everybody actually parades, it's not like you stay in the sides of the street and look at the people - everybody participates.

I used to live in New York for eight years, and I saw many parades there too. It's more political in Uruguay still. Each year the issues change a little bit.

Last year we were in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, but in Uruguay we didn't see the first peak of the contagions until after December.

It was quite crowded actually. I was a little worried, because a lot of young people weren't using masks, dancing very close to each other. But after there wasn't a peak of cases.

Vaccination is happening very fast, and for September, we assume the 2021 situation will be similar to last year and that restrictions will be lifted by then.

We are very lucky that we're in a mostly secular society. Homosexuality was legal in 1934. In other countries, it's still illegal. This is something we have to see as a very good thing to happen in Uruguay.

A lot of people in the community are conscious of the fragility of our rights. We have to be very careful and diligent about our rights because they are very easy to destroy.

Our Pride is to be fully integrated into society - society doesn't need to have special places where LGBT people have to go to feel comfortable. We will feel proud of our society if our society fully understands the importance of having full integration - not only sexual orientation and gender identity, but race and religion too.

Amy Gall, United States

'Sometimes it's just the most magical thing to inhabit this space where you're in the majority'

There's lots of different ways to do Pride in New York.

I haven't gone to the official Pride parade in a very long time because it's so corporate now. It's basically a bunch of straight people on a Citi Bank [a major US bank] float at this point.

But the thing that is great about Pride here is everybody is just around, and I can be around queer people en-masse in a way that doesn't normally happen and hadn't happened at all in a year-and-a-half because of Covid.

Amy Gall

Amy GallFor Brooklyn Pride, there was just a whole block of queer people and trans people dancing to [pop star] Robyn and it was wonderful, and I had forgotten how much I needed that. Sometimes it's just the most magical thing to inhabit this space where you're in the majority and feel like you're a part of something.

When you think about what's being represented on TV or music, when you think of all the money being thrown at pride and representation right now, it's still very much centred on gay men.

I identify as a lesbian or a dyke, and I think lesbians definitely have less space in the conversation than say gay, cis men, because of the intersection of gender, economic power and queerness. It's a space I don't always see centred, but at the Dyke March, which I'll go to on Saturday, it is.

I live in New York City, which most people think of as a very progressive, LGBT-friendly city.

As someone who used to work with at-risk LGBT youth who, still in this city, are homeless at rates that are three-times that of straight kids - that fight is never going to be over and it's always going to be taking place in "liberal" cities.

In other places the US, trans people are having to fight for their rights to play sports, and trans youths are having to fight for their rights to have access to healthcare.

I think of Pride as a space to hold two things: One, I am happy and I'm experiencing joy and gratefulness for people who I have in my life. But two, that there's just a lot of change to be done.

It's bittersweet - but I think it's very important to experience joy and have fun.

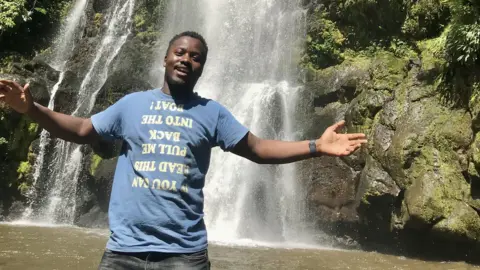

Michael Kajubi, Uganda

' I see Pride as a time of reflection'

I lost my job while in Uganda on suspicion that I was part of the LGBT community. At that point I knew the road had come to an end - it would be very hard for me to find an employer.

That's why I started a travel company, McBern Tours, in 2013. I was employing myself and also other people like me who were facing discrimination. The proceeds from the travel company would later build McBern Foundation, which supports the elderly and LGBT youth at risk in Uganda. While I served all clients, the business was known to be gay-owned and to be welcoming to the LGBT community.

A year later, Uganda signed an anti-gay bill into law.

When that became official, I had a company I had partnered with that was going to send me 60 clients every year to tour Uganda.

But when the bill was passed, they cancelled the partnership. They felt that since some of the clients were gay, they didn't feel they'd be secure in Uganda, that's number one. And number two, they didn't want to spend their money in a country that criminalises the LGBT community.

Michael Kajubi

Michael KajubiI had to get back to the drawing board. At that point we had to be very careful - If I used one car going out, I wouldn't use the same car coming home because I could be a target.

Thanks to the work of activists and campaigners the bill was repealed - but now they're trying to bring in the "sexual offences" bill that would criminalise homosexuality.

The LGBT community in Uganda connects mostly through social media and also dating apps. Ideally, whoever is on those dating sites is one of us or part of the community - unfortunately sometimes people who are there aren't, so you have to be very, very careful.

When you meet someone, they tell you who else is organising a house party and then you go and you meet many other people. That's how we meet others like us.

My first Pride festival was in 2015. I was still a little scared, but I felt so good. I had a sense of belonging, like 'yes these are my people'. I was so happy. It was a great feeling to be part of my community, to raise the flag without fear of judgement or discrimination from the feeling around me.

But that was the end - there was never any other Pride in Uganda.

I don't want to see Pride as a celebration. I already see Pride as a time of reflection. Gratitude for what has happened, but then, something that reminds us it's not yet over. There are so many countries that are still discriminating against us.

In 2020, I moved to Canada due to the threats on my life I was facing back home. Much as I am in a safer place now, I'm still fired up to fight on for those back home and in other parts of the world that still face persecution. My dream is to see that LGBT youths in these places get the skills to elevate them to a level of financial independence where they can contribute to their local economies and have better political bargaining power.

Interviews by Robin Levinson King of BBC North America