Coronavirus: Why attitudes to masks have changed around the world

Reuters/Andrew Parsons Media

Reuters/Andrew Parsons MediaIn the past few days, both US President Donald Trump and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson have been seen wearing masks in public for the first time.

It's a dramatic turnaround - Mr Trump previously mocked others for wearing masks, and suggested some might wear such personal protective equipment to show their disapproval of him, even after the US Centers for Disease Control recommended face coverings.

Meanwhile, the UK government was initially reluctant to advise the general public to wear face coverings, even as other countries in Europe did.

It introduced rules requiring people to wear face coverings on public transport in June, and now says people in England must wear face coverings in shops or face a fine.

Globally, many authorities - including the World Health Organization (WHO) - initially suggested that masks were not effective in preventing the spread of the coronavirus. However, they are now recommending face coverings in indoor spaces, and many governments have even made them mandatory.

What's changed - and why?

The number of governments recommending face coverings has gone up significantly over the past six months.

As of mid-March, about 10 countries had policies recommending face coverings - now more than 130 countries and 20 US states do, says Masks4All, an activist group of researchers that advocates the use of homemade masks during the pandemic.

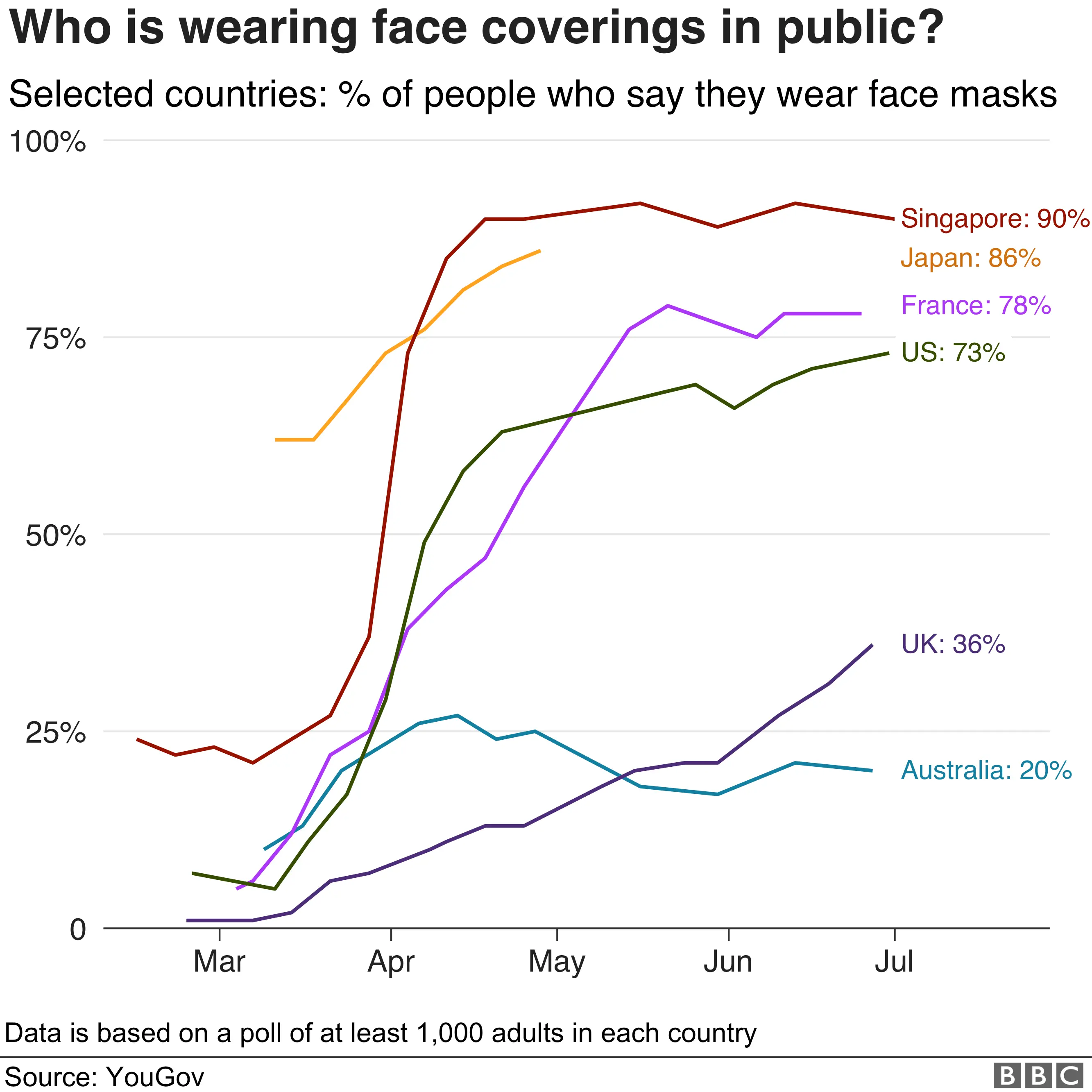

Some studies also suggest that people's attitudes have changed.

"Countries with no previous history of wearing face masks and coverings amongst the general public rapidly adopted usage such as in Italy (83.4%), the United States (65.8%) and Spain (63.8%)," says a report by the Royal Society - one of the leading science bodies in the UK.

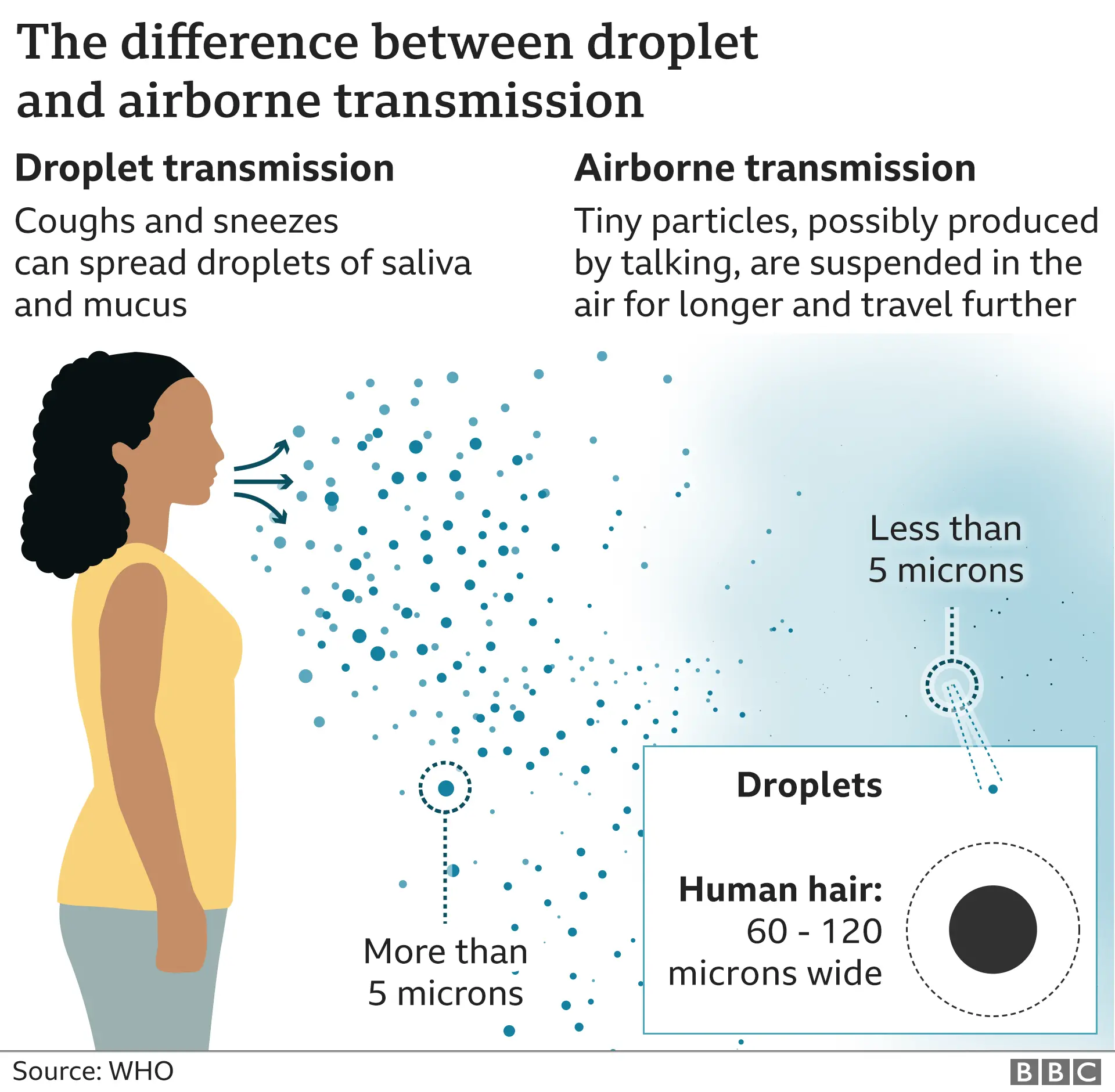

The changes appear to be partly due to a better understanding of how Covid-19 spreads.

Initially, the WHO said masks should only be worn by medical workers, or people who had symptoms like coughing and sneezing.

However, in recent months, there's been increased evidence that many people with the virus do not have symptoms - but can still be contagious - and masks can stop them from passing it on to others. The WHO changed its guidance in June.

Meanwhile, there is more awareness that the risk of transmission is higher in poorly ventilated indoor spaces - and evidence to suggest that the virus could be spread by tiny particles suspended in the air.

This means that if everyone wears face coverings it will "protect against the most common mode of transmission - droplets - and to some extent maybe aerosol droplets," says Kim Lavoie, chair of behavioural medicine at the University of Quebec at Montreal's psychology department.

Prof Lavoie adds that "there has been increased research" into face coverings, including observational studies which indicate "countries with high mask wearing seem to have lower infection rates".

Furthermore, a number of scientists now say there is "some evidence" that masks can protect the wearer as well as those around them.

There is also growing acceptance that the pandemic could continue for a long time - and, if so, face coverings could be seen as something necessary to help people adapt, and reduce risks as businesses and schools re-open.

"Covid's not going anywhere - we'll probably have a vaccine in years, not months," says Prof Lavoie, who has been leading the iCARE Study, an international survey into Covid-19 related behaviours. "So all these principles need to be integrated and adapted to the new normal life."

Why do countries have such different attitudes?

Even as government policies have changed - there's a big gap in how willing people are to wear masks.

About 83% of people in Italy, and 59% in the US, say they would always wear a face mask outside their home - but only 19% of people in the UK say the same, according to the Covid-19 Behaviour Tracker - a project run by the Institute of Global Health Innovation at Imperial College London with polling company YouGov.

"The US, UK and Canada have been relatively slow to accelerate mask wearing versus, for example, Spain, France and Italy," says Sarah P Jones, a health behaviour researcher at Imperial College London, and one of the creators of the tracker.

She says mask wearing can vary based on how vulnerable people feel about an illness, whether they believe the costs outweigh the benefits, and how readily available masks are.

In countries with steep rises in mask wearing, people may have experienced "rapid increases in perceptions of severity and vulnerability", "rapid policy changes mandating use of face masks", and a sense that "I see lots of other people doing it, so it must not be a big deal to wear a mask".

Prof Lavoie agreed that places that "got hit quickly and hard", like Italy, may have adopted mask wearing more readily.

Finally, people in countries that experienced the 2003 Sars pandemic - or other respiratory outbreaks - were readier to start wearing masks.

"In East Asia, there's plenty of recent memory of respiratory pandemics, and a cultural awareness that masks are a good idea," says Jeremy Howard, a research scientist at the University of San Francisco, and one of the Masks4All founders.

By contrast, "there's just no recent history of respiratory pandemics in the West" and many Western and international institutions have "almost entirely ignored East Asian scientists", he argues.

Reuters

ReutersMany countries were particularly cautious over recommending face masks because of a lack of clinical trials proving their effectiveness, says the Royal Society's report.

However, "there have been no clinical trials of coughing into your elbow, social distancing and quarantine, yet these measures are seen as effective and have been widely adopted," it adds.

Why are some still reluctant to wear masks?

A majority of countries now recommend or require face coverings in some situations.

However, most people still appear much more willing to use hand sanitiser, social distance or wash their hands regularly, than wear face masks, according to data from both the Covid-19 Behaviour Tracker, and iCARES.

People feel that hand washing and social distancing are things they can easily control, says Prof Lavoie.

By contrast, "mask wearing is a little more complex - you have to find and purchase a mask, put it on and dispose of it a certain way, and they're uncomfortable to wear."

And the changing guidance from the WHO and many governments could have caused difficulties.

Many experts believe that governments were reluctant to recommend face coverings because they feared there would be a shortage of PPE equipment for medical workers - but by suggesting that they were ineffective at preventing transmissions, they now sound inconsistent.

"Mixed messaging, not being transparent about data, or how the government makes certain policy decisions, can undermine trust" and make it harder to convince people to wear face coverings now, Prof Lavoie says.

Mr Howard believes that many governments in the West were slow to act on masks until they were badly affected by the pandemic.

Nonetheless, he thinks that Boris Johnson and Donald Trump can have a positive impact now by wearing masks publicly.

"Role models are absolutely real," he says, and ever since Mr Trump wore a mask, "a lot of folks who were previously anti-mask are now saying that was a patriotic thing for him to do."

This is especially important now that the US is experiencing a new wave of infections, he adds.