Iran tanker seizure: What's so important about a ship's flag?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe cargo ship Stena Impero, seized by Iran last week, was sailing under a British flag - but it was owned by a Swedish company and had no British nationals on board.

It's very common for ships to fly the flag of a country that differs from that of the owners.

But why is it done and who benefits?

What do Liberia, Panama and the Marshall Islands have in common?

Every merchant ship must register with a country, known as a flagged state.

Under the open-registry system, "flags of convenience" as they are sometimes known, can be flown by any vessel regardless of the nationality of the owners.

Other systems of flagging have tighter rules on who can own and operate these vessels.

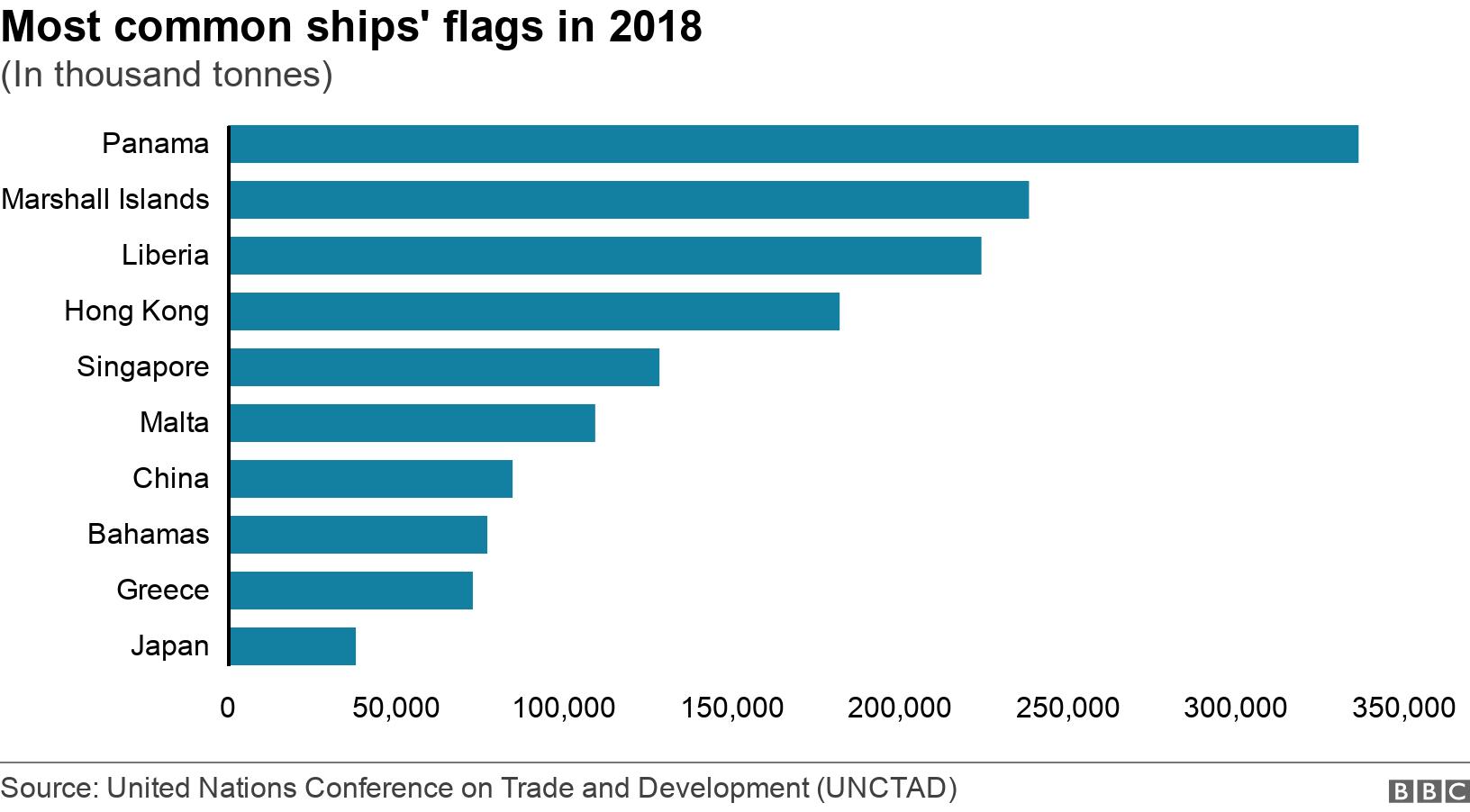

Panama, the Marshall Islands and Liberia are the leading flag states.

Erwin Willemse

Erwin WillemseThere are about 1,300 vessels listed on the UK Ship Register.

This Red Ensign Group, which includes the United Kingdom, the Crown dependencies (the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey) and UK overseas territories (Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Montserrat, St Helena and the Turks and Caicos Islands) is the ninth largest fleet in the world.

Why choose a flag other than your own?

Ship-owners choose a flag state for a range of commercial reasons.

They include regulations, taxes and the quality of the service provided, maritime security expert Ioannis Chapsos says.

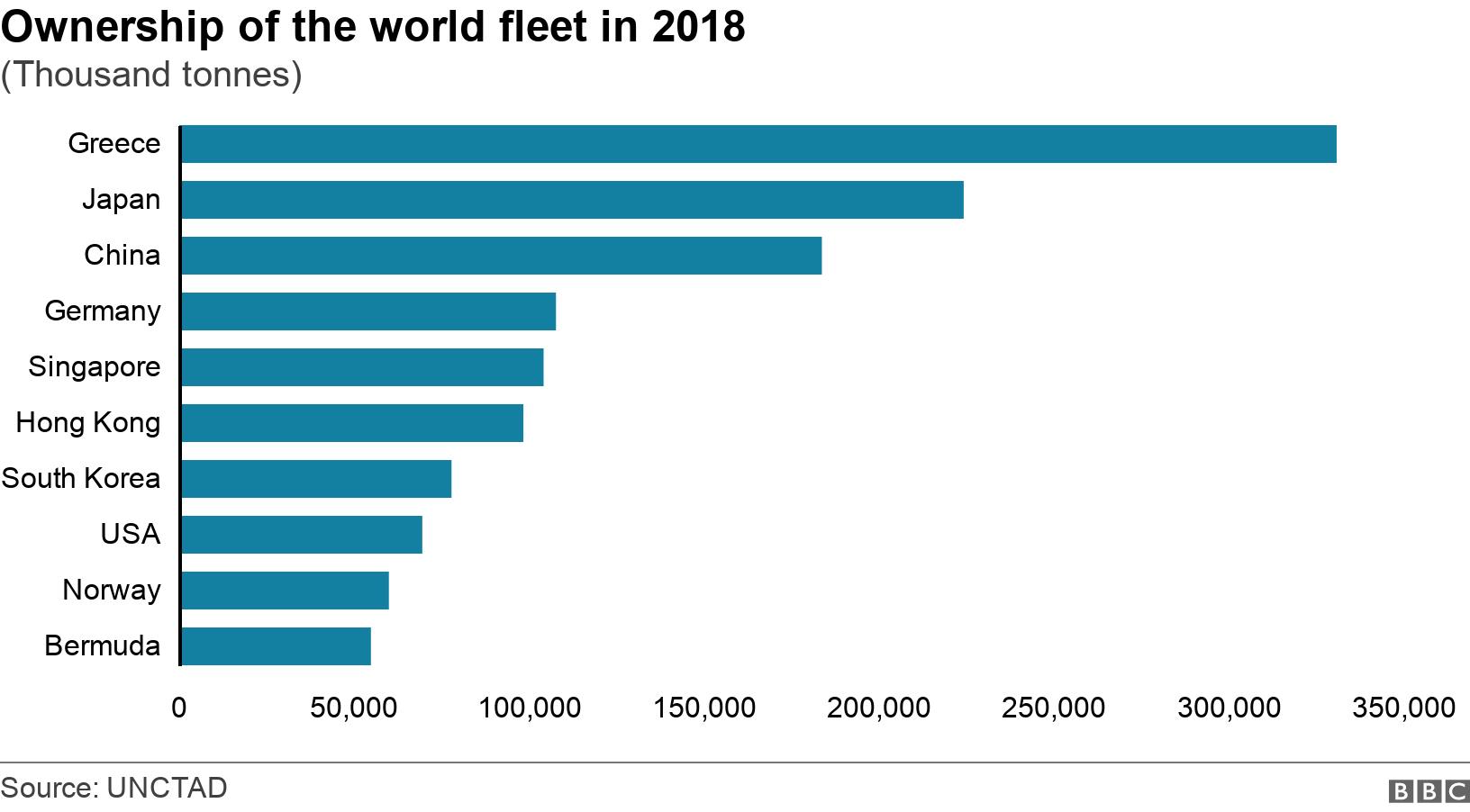

He points to Greece - the world's leading ship-owner. Many of its vessels do not fly the Greek flag, a big factor being they would have to pay more tax.

In return, the flag states, often poorer countries, earn money.

The Panamanian ship registry contributes tens of millions of dollars to the country's economy.

The system allows for the hiring of crew from anywhere in the world, which can lower costs.

This system of "flags of convenience" has been criticised because of the potential for looser regulation and even the flouting of international maritime rules. But shipping practices are generally seen as having improved significantly in the past three decades.

AFP PHOTO / FREE NAZANIN CAMPAIGN

AFP PHOTO / FREE NAZANIN CAMPAIGNThe term is not used by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the UN's shipping agency.

And it's "almost regarded as a swear word in the shipping industry", says Simon Bennett, of the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS).

He says owners tend to choose to register with a flag state based on reputation or because major shipping registries have a presence in every major port.

The safety record of large open registries, he adds, matches the so-called traditional flags.

The system, however, still faces criticism.

Registering under a different flag makes it more difficult to hold ship-owners to account over wage disputes or working conditions, according to the International Transport Workers' Federation.

EPA

EPAWho's responsible?

After signing up to a flag, the laws of that country are conferred on the vessel and each country is responsible for ships flying their flag.

This includes ensuring that ships conform to relevant international standards - through survey and certification of ships, says the IMO.

Flag countries sign up to international maritime treaties and are responsible for enforcing them, with rules set by the IMO in regards to the construction, design, equipment and manning of ships.

Under the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea, flag states are required to take measures for ensuring safety at sea.

Who runs the registry?

It's common for a flag registry to be managed in a different country.

Take Liberia, for example, which is administered by an American company with its headquarters in Washington DC.

The land-locked Mongolia Registry is based in Singapore.

The Comoros Registry is based in Bulgaria.

Far-flung Vanuatu has its base in New York.

The unusual geography of the registry system can pose security challenges.

It's unrealistic for a flag state to provide security to all the vessels registered to it, says Mr Chapsos, even though vessels are essentially an extension of that state.

And it is even harder for a state with far fewer resources than, for example, the Royal Navy but significantly more commercial ships.