Surrogate mothers: 'I gave birth but it’s not my baby'

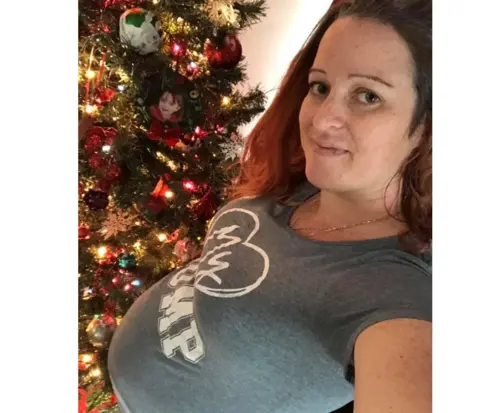

JENNIFER JACQUOT

JENNIFER JACQUOTCanada has become a hot destination for parents-to-be looking for "altruistic surrogates" - women who give birth to babies they are not genetically related to and only charge pregnancy-related expenses in return.

Marissa Muzzell spent 16 hours in labour to deliver a baby girl.

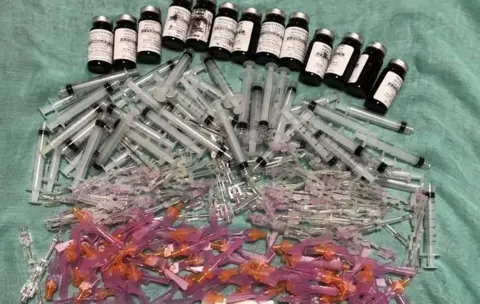

She suffered from acute morning sickness during her pregnancy and had to be hospitalised twice. She underwent months of daily hormone injections and previously endured four failed embryo transfers.

She did all of this for a baby that is not hers.

Marissa, 32, is a surrogate in Canada, where hundreds of women like her volunteer to give birth to children that will then go home with somebody else.

"I've just created [a] family… someone else's family," says Marissa laughing, still recovering in the delivery room after handing over the newborn to the baby's parents - a same-sex couple from Spain.

Surrogacy around the world

- Thailand, Nepal, Mexico, and India, have all recently banned foreign commercial surrogacy

- Several countries including France, Germany, Italy and Spain prohibit surrogacy in all forms.

- In countries including the UK, Ireland, Denmark and Belgium, surrogacy is allowed only when the surrogate is not paid, or only paid for reasonable expenses.

- Commercial surrogacy is available in countries such as Georgia, Russia, Ukraine, as well as some US states.

There is a steady surge in demand for surrogacy globally. Canada has experienced dramatic growth in the practice, with some estimates suggesting an increase of more than 400% in the past decade.

Surrogacy here is "altruistic" - meaning the women who carry the babies cannot make a financial gain out of it. Canada is not the only country where this type of surrogacy is the norm - this is also the case in the UK, for example.

But the legislation in most Canadian provinces makes it easier for intended parents to obtain legal parenthood of a surrogate baby. Also, unlike some other countries, Canada opens this practice to same-sex couples and single parents.

Altruistic surrogacy is more ethically acceptable for some and also a lot cheaper, compared to countries where surrogacy is commercial, such as the US.

"I see a lot of American surrogates who get paid thousands of dollars just to get pregnant, whereas in Canada we don't do that," says Marissa.

Here, surrogates only get reimbursed a capped amount of pregnancy-related expenses, like antenatal vitamins, maternity clothes, groceries and travel costs for medical appointments, as well as lost wages if they take time off work due to medical reasons.

And they need to produce a receipt for every expense they claim.

"This is not an income that you can save, we're not baby machines," says Marissa, who works as a youth worker.

"To me that made it that much more special. You're not doing it as a job, but from the kindness of your heart"

'Online dating'

Canadian surrogates are gestational carriers, which means that the embryo transferred into their womb is created in a lab with someone else's egg, never their own.

There are at least 900 active surrogates, according to estimates from Canadian media - and official statistics are hard to come by.

"Eleven years ago, when I started the company, we had eight [surrogate] babies born in a year. In the last month alone we've had over 30 babies born," says Leia Swanberg, founder of Canadian Fertility Consultancy, one of the largest surrogacy agencies in the country.

The volunteers must undergo medical and psychological evaluations, and need to have given birth to at least one child of their own.

Ms Swanberg, a former surrogate herself, vets them and helps match them with intended parents across the world.

"It is like online dating," says two-time surrogate Janet Harbick, 33, who is currently pregnant with a baby girl.

"You have to fill in a profile, then you get sent profiles from intended parents".

"It is always hard. There are more couples than surrogates, so you feel very responsible. How do I choose? There's a connection, you simply feel it when you first make contact."

Janet had her first surrogate baby last year for a French couple, and then became pregnant again just four months after giving birth.

JANET HARBICK

JANET HARBICK"I've already thought of doing two more, a sibling journey for each couple I've had a baby for, to give them brothers or sisters," she says.

"I love being pregnant and my body heals well, so why not? I will keep on doing it for as long as my body allows."

Like her, many surrogates volunteer multiple times. Most also keep in contact with the families they help create.

"These guys [the intended parents] start off as strangers, then they become friends, eventually they become family," says Janet.

"They are uncles to my kids, and I'm in my 'surro' baby's life for the long run."

These women agree that surrogacy is a life-changing experience, which may partly explain why they give up their time and put their bodies at potential risk.

"I cannot imagine life without kids," says mother-of-five Janet.

"My tubes are tied and I don't want any more, but I love the feeling that I'm able to produce this for someone who couldn't have it any other way."

Marissa says: "I think it's just bringing light back into the world. I'm creating a child for these gentlemen but I'm also creating a legacy."

Tough road

Yet the road to having a surrogate baby can be lengthy and tough.

Multiple rounds of IVF, failed embryo transfers and miscarriages are common.

"I was very, very sick during the pregnancy, so my husband had to cover for me. He was super-supportive and so were my kids," says Janet.

"In my case, my fiancé gave me a hard time - he never understood why I was doing this," adds Marissa.

Being from a small rural town, she also found it difficult to avoid criticism from neighbours.

"I got a lot of: 'How could you give up that baby?' 'Why are you sacrificing your family life for a baby that you won't bring home?'

"So if you want to be a surrogate, you need to stick to your guns. It's your body, your choice."

JANET HARBICK

JANET HARBICKCriticism of surrogacy is not uncommon.

Within feminism, for example, there is a school of thought that views it as a form of exploitation of the female body.

Academic Katy Fulfer, from the University of Waterloo, conducts research into surrogacy and says even though surrogacy in Canada is unpaid it does not mean there is no exploitation.

"I think comparing surrogacy and prostitution is appropriate, as you have two forms of embodied labour that people are selling," she says.

"The fact that women don't get paid is problematic, because fertility here is a for-profit industry and everyone else gets paid. Why isn't the surrogate getting paid?"

Within the altruistic model, surrogates only get expenses reimbursed while agencies, doctors, lawyers and fertility clinics are paid a fee - making it an expensive endeavour for intended parents that may cost more than C$75,000 ($56,767; £44,600).

The model is highly regulated. A few years ago agency owner Leia Swanberg became the only woman ever to be charged under Canada's law governing surrogacy.

She pleaded guilty to failing to keep track of all receipts for compensation paid out to the surrogates at her agency and was fined.

There is currently a big push to change this legislation.

"As compensation is banned, even sending flowers to a surrogate could expose intended parents to criminal liability," she says.

A breach could lead to fines of up to C$500,000 ($378,450; £297,300) or a 10-year jail sentence.

"In truth, it would be good to have more relaxed regulations and not have to collect receipts, but it's not a big deal. We are not in this for the money," says Janet.

"I'm proud, very proud that I'm able to carry this child."

"You are making brand new parents," adds Marissa.

"I handed this baby back to them with joy, because this baby was never mine".

"Think of surrogacy as extreme babysitting. In the end, the baby gets to go home to its parents. There isn't much more to it than that."

Listen to the documentary "The Surrogates Club"

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year and shares their stories.

It's been a momentous year for women's rights around the globe, so in 2018 BBC 100 Women will reflect the trailblazing women who are using passion, indignation and anger to spark real change in the world around them.