Puerto Rico hurricane: How was the 3,000 death toll worked out?

Getty Images

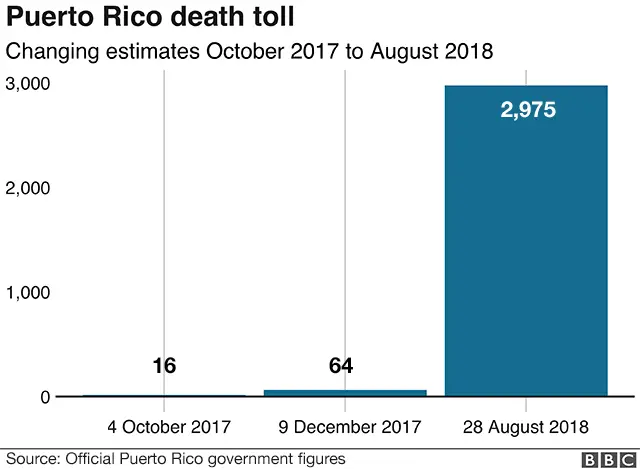

Getty ImagesUnited States President Donald Trump has disputed official findings that nearly 3,000 people died in Puerto Rico as a result of last year's hurricane.

He added that the death toll had been inflated by adding people who died of other causes.

"If a person died for any reason, like old age, just add them on to the list," he tweeted.

Twitter

TwitterAllow X content?

So is he correct to say this figure is wrong?

Nearly every study and report into the hurricane estimates a significantly higher toll than the early official estimates mentioned by the president.

The number of nearly 3,000 was released last month after an independent study by the George Washington University (GWU) in July, which was commissioned by the governor of Puerto Rico.

It found that 2,975 people died in Puerto Rico as a result of Hurricane Maria.

Since the hurricane struck in September last year, several investigations by academics and journalists suggested the death toll was much higher than the official count, which for months stayed at 64.

For the first few weeks, the death toll was only put at 16.

The task of counting the dead immediately after or in the months following a major disaster is not an exact science.

There are also no state or federal guidelines in the US for calculating storm or hurricane-related deaths.

The GWU study concluded the initial death toll only included those killed directly by hurricanes Maria and Irma - either by drowning, flying debris or building collapse.

GWU researchers also counted those who died in the six months following as a result of poor healthcare provision and a lack of electricity and clean water.

How did they get their figure?

The key part of the research is an estimate of "excess mortality" from September 2017 to February 2018.

Put simply, this is the difference between the predicted normal death rate if the hurricane had not struck (estimated using historical data), and the actual death rate for the period afterwards.

The researchers also factored in migration away from Puerto Rico in the wake of the storms.

"Overall, we estimate that 40% of municipalities experienced significantly higher mortality in the study period than in the comparable period of the previous two years."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRecording the deaths

One important issue the GWU study raises is the process of recording deaths after the hurricane.

"Most physicians receive no formal training in death certificate completion, in particular in a disaster," it states.

Some of those they interviewed showed a reluctance to record deaths as hurricane-related.

The report also points to major communication and infrastructure problems which delayed the relaying of important information about health issues and procedures for recording deaths.

"Physician unawareness of appropriate death certification practices.... and the government of Puerto Rico's lack of communication about the death certificate process...substantially limited the count of deaths related to María."

How reliable is the study?

Head of statistics for BBC News, Robert Cuffe, describes the GWU report as "comprehensive".

He says it is more robust than an earlier study by Harvard University that concluded there could be a death toll ranging anywhere from 793 to 8,498.

Most media reporting of that study used the midway figure of 4,645 "excess deaths" - the number of deaths over and above what would be expected for the period from 20 September to 31 December 2017.

However, the Harvard researchers pointed out they were not giving a precise figure, and that there was an element of uncertainty in their estimates.

Mr Cuffe adds: "Can we say that every extra death that happened up to six months after the hurricane was caused by it? Not definitively.

"Some extra people will have died of old age earlier than they would have if there'd been no hurricane."

But does that mean the hurricane killed them?