Russian spy: How big is the Kremlin's diplomatic network?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRussian diplomats are being expelled by more than two dozen countries, following allegations - which it denies - that it poisoned a spy in the UK. How much difference will that make to Russia's extensive international presence?

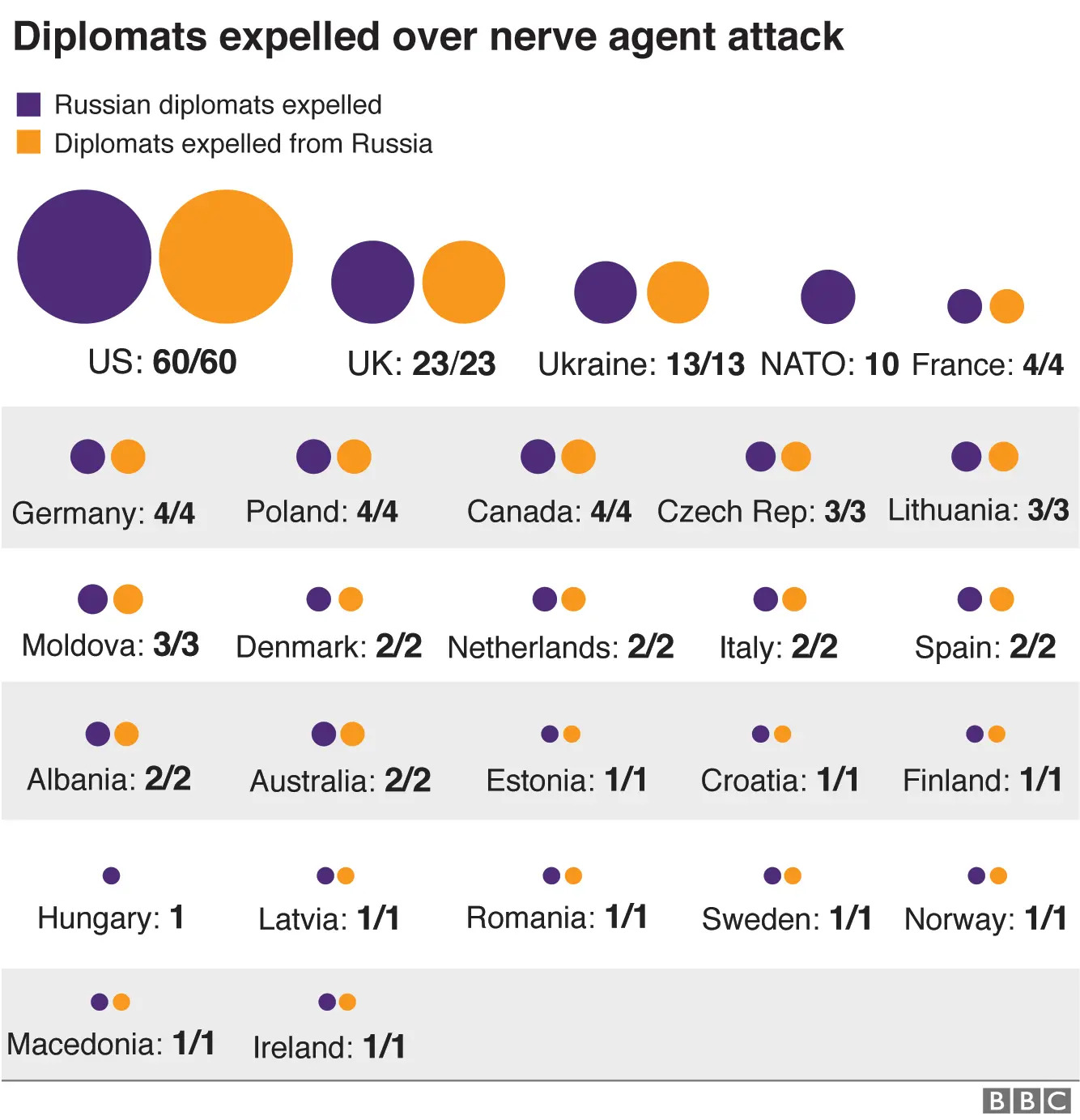

The decision to expel more than 140 diplomats from Russia's embassies will sting - causing it more than just irritation and inconvenience. It has also announced the tit-for-tat expulsions of dozens of diplomats from mainly Western countries.

But the numbers involved are a tiny part of Russia's large international presence.

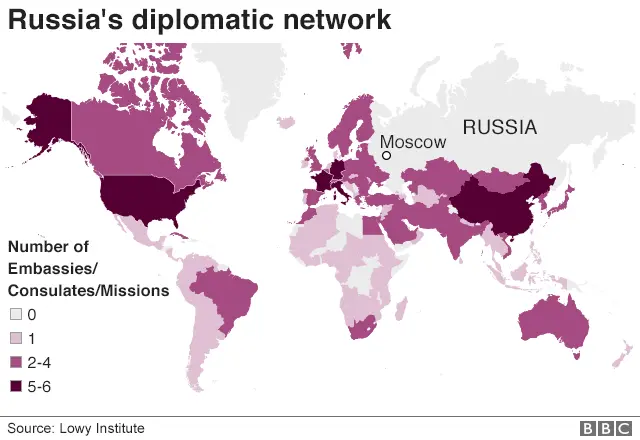

Russia has 242 diplomatic posts around the world, with 143 embassies, 87 consulates and 12 other diplomatic missions.

Its global network covers 145 countries.

In terms of sheer size it ranks fourth in the world, according to the Lowy Institute's 2017 Global Diplomacy Index, which maps and ranks 60 of the world's most significant diplomatic networks.

Only the United States, China and France have a larger network. The United Kingdom, which ranks seventh on the index, has 225 posts worldwide.

Russia is also expanding its network in strategic locations.

For example it is significantly increasing the size of its Dublin embassy, according to reports.

Seen in this context, the expulsions appear to be less momentous than at first glance.

The co-ordinated actions of the countries that expelled Russian diplomats have been described as the largest in memory.

Memories can be short, of course.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn mid-2017, Russia itself ordered the removal of 755 members of staff from US diplomatic missions in Russia, in response to sanctions over the annexation of Crimea and allegations of interference in the US elections.

However, the number of actual diplomats expelled was lower because many staff at the US embassies were Russians employed for domestic and administrative services.

Russia, by comparison, does not employ local staff at its missions, probably for security reasons.

Nevertheless, the 2017 episode gives an idea of the sheer scale of both countries' diplomatic presence.

The US State Department has 74,400 employees, 13,700 of whom are in the Foreign Service, with 9,400 posted overseas.

Precise numbers for Russia's foreign service are elusive, but it is likely to have several thousand diplomats. This would not include the undeclared or covert intelligence agents working outside the walls of its embassies and consulates.

In contrast, the UK's Foreign Office has more than 1,600 diplomats posted overseas.

In the UK, 58 Russian diplomats are listed on the UK government's London diplomatic list.

Britain's expulsion of 23 of these officers, therefore, almost halves the size of Russia's mission in London, although the remaining 35 is still a significant contingent.

In the US, which ordered the closure of the Seattle consulate and the expulsion of 60 diplomats, the Washington DC embassy alone has 116 diplomats.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn addition, Russia has its New York mission to the United Nations - which plays a key role in its international diplomacy - and three consulates, with about 50 officers.

There are also cultural offices, trade offices, an information office and a defence, military, naval and air attache office in the US.

Russia could be said to be punching above its weight if its diplomatic presence is compared with its global size on most key measures.

It has a military budget about a tenth of the size of the US's, and less than half that of China's, but its diplomatic network is almost the same size as both. It has the eighth largest population and the 12th largest economy in terms of GDP.

Its extensive diplomatic network reflects both its imperial history as a great power in the 19th Century, as well as its Cold War posture. It has a multitude of posts in Eastern Europe and former communist allies including China, Vietnam, Cuba and Angola, as well as legacies of the former USSR in Africa and Asia.

The size of its network reflects the extent of its undiminished global ambition.

The expulsions this week, while significant, may therefore pose only a temporary setback for Russia's diplomatic influence.

However, having a reduced diplomatic presence in the countries who have expelled Russian officials, plus Nato, will impair its efforts in those countries and reduce its trade and cultural activities.

More importantly, though, the cuts may make a sharper dent in its intelligence capabilities, at least in the short term.

It's probable that the expulsions focus on known intelligence agents: Australia for example explicitly identified two expelled officers as "undeclared intelligence agents" - a description the UK also used for all 23 diplomats it expelled.

It may take some time for Russia to replace the agents it has lost with new ones, either within embassies, or outside the protection and immunity of its official diplomatic corps.

More stories like this:

For Russian President Vladimir Putin, himself a former KGB agent, the damage to the Russian intelligence gathering capabilities will be keenly felt.

Russia's decision to expel UK and US diplomats was followed by action against other countries which had expelled its diplomats. It has warned that further expulsions may yet be announced.

These reciprocal expulsions inflict pain on both sides. Russia is the world's largest nation, a permanent member of the Security Council, a top 12 global economy and a leading producer of oil and gas: other countries benefit from having their envoys in Moscow.

Meanwhile, the investigation of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which is analysing the substance used in the Skripal poisoning, is continuing.

Should the results of that investigation provide evidence of Russia's involvement, the rift between Russia and the rest of the world is only likely to widen.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Alex Oliver is research director at the Lowy Institute. She had input from Kyle Wilson, Russia expert at the Centre for European Studies at Australian National University.

More details about the Lowy Institute's work can be found here.

Edited by Duncan Walker