Covid inquiry's biggest revelations of first Wales week

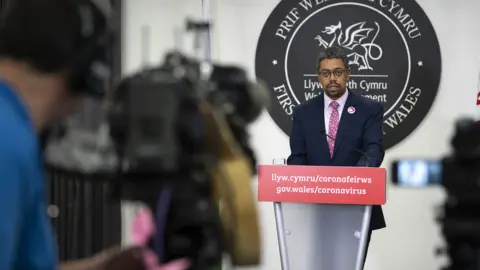

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK Covid Inquiry has spent its first week in Cardiff scrutinising the Welsh government's handling of the pandemic.

So what are some of the most notable things we've learned so far?

The inquiry is investigating the decision-making of the UK government and devolved governments in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Since the start of the pandemic in March 2020, more than 12,000 people in Wales have died with Covid.

The Welsh government didn't expect to be in charge

The pandemic gave the Labour Welsh government an unprecedented role in people's daily lives - deciding where they could go, who they could see, even what they were allowed to buy in the supermarket.

Up to 700,000 viewers would tune into its televised briefings on the BBC to find out the latest rule changes for Wales.

What is now clear is that until just a few days before the first lockdown in 2020, ministers in Wales did not actually expect that level of control.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe evidence from Prof Dan Wincott from Cardiff University suggests that before 20 March the working assumption for Mark Drakeford and his cabinet was that the UK government would be making the big decisions under civil contingency legislation.

However, it soon became clear those laws couldn't be applied, and so health legislation was used instead.

This meant that three days later, when the shutters came down on businesses and we were told to stay at home, it was ministers in Cardiff Bay who decided what happened next in Wales, as health is a devolved matter.

By May 2020, it became clear that Mr Drakeford's government wanted to ease restrictions at a far slower pace than over the border in England.

The following October the Welsh government was emboldened to launch its own lockdown without co-ordinating with other parts of the UK.

The pandemic is now seen by some as the time when devolved government in Wales came of age.

Whether true or not, things could have been very different if the Welsh government had not been put in charge.

Ministers knew there were problems

We expect to hear from the politicians later in the hearings, but we are already getting a picture of who knew what and when.

An email shown to the inquiry revels how, a day after the first lockdown in March 2020, then Health Minister Vaughan Gething sent himself a message spelling out concerns by frontline staff.

It read: "Complete chaos at our hospital. No protection for nurses, very low morale… masks not being released".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnderneath, in brackets it reads "from at consultant at PCH" which we believe was Prince Charles Hospital in Merthyr Tydfil.

This is very different to the picture Mr Gething had painted earlier in a statement released in March that spoke of "early and decisive" action being taken to protect communities and ensure there were "timely preparations" for an expected surge in cases.

Deleting messages was the default

The strength - or not - of the Welsh government's preparations is something Mr Gething is likely to be quizzed on when he gives evidence.

As is his use of WhatsApp messages and vitally, why some were deleted from Mr Gething's phone.

This has already been a tricky subject for ministers elsewhere in Westminster and Scotland.

The Welsh government has always insisted that it did not use informal messaging systems for making decisions. However, that may be difficult to prove when some of the messages have disappeared.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe inquiry has heard claims that Welsh government senior special advisers "suspiciously and systematically" deleted communications - and requests were sent to clear out WhatsApp chats at the end of every week.

It was also told that Mr Gething turned on a disappearing messages function which meant his communication would be deleted by default.

Was this simply good phone memory management or something else? The inquiry will want to know.

It's not just politicians who disagree

We are already familiar with the feuds between politicians during the pandemic. Several times during 2020 Mr Drakeford made a point of saying he had not been able to speak to Prime Minister Boris Johnson about key decisions.

He was later caught on camera describing the former prime minister as "awful". What we are starting to see in the inquiry evidence is that there was also some tension within the scientific community.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn his evidence to the inquiry Dr Robert Hoyle, the Welsh government's head of science, explained how, in early in 2020 his view of the pandemic differed to his boss, Prof Peter Halligan, the chief scientific adviser.

By mid-February he said he had become alarmed and realised a major public intervention would be needed. But when he raised the issue he was given the impression that it was "someone else's problem" and the subject was not escalated until a week before the first lockdown.

Later on, while other nations made the use of facemasks mandatory, the Welsh government resisted.

Dr Hoyle says he disagreed with the decision made by Dr Frank Atherton, Wales' chief medical officer, who is due to give evidence next week.

Dry pubs don't help

Back in November 2020, publicans and politicians joined to criticise the Welsh government's decision to stop pubs and restaurants selling alcohol.

At the time, Mr Drakeford said the changes, which included having to close completely at 18:00, could save more than a thousand lives.

Wales wasn't alone in limiting alcohol sales as a public health measure - but did it work? According to Dr Roland Salmon, a retired epidemiologist who used to work for Public Health Wales, there was no real scientific rationale.

He told the inquiry the idea of a "no alcohol pub" made no real sense - once people were gathered together it didn't matter what they were drinking.

What then was behind the pandemic prohibition?

According to Dr Salmon it was perhaps more down to "an overly enduring legacy of the chapel heritage".