'Joyful' art helps shine new light on colonial history

Jasmine Violet

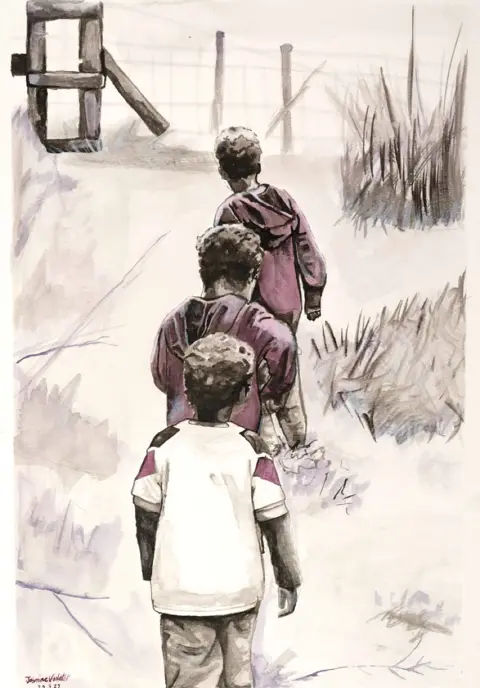

Jasmine VioletThe picture is a pastoral scene - three young black boys heading out into the countryside, perhaps to find adventure.

It has something of the quality of a children's story book from times gone by, like a scene from an Enid Blyton tale.

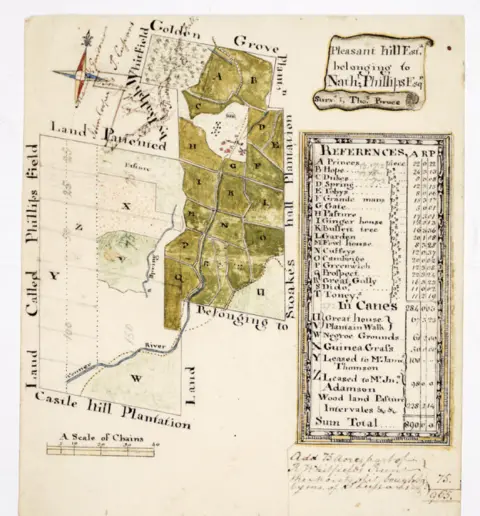

So it may come as something of a surprise to discover that the inspiration behind the picture came from a map showing the details of a much less idyllic place - a sugar plantation in 18th Century Jamaica, worked by slaves, who could conceivably be the distant ancestors of those happy children.

The piece is by west Wales artist Jasmine Sheckleford James, who works under the name Jasmine Violet.

It was the result of a commission by the National Library of Wales to examine items with links to colonialism from different perspectives, and broaden diversity in its collection and contributors.

Jasmine Violet

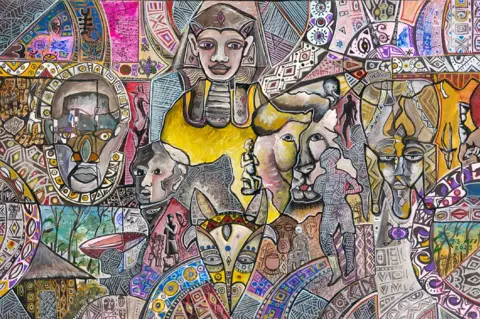

Jasmine VioletShe is one of four artists, alongside Mfikela Jean Samuel, Dr Adeola Dewis and Joshua Donkor, who have created new pieces for the library, using something from the existing collection as an inspiration to shine a new light on the experience of colonialism.

Jasmine, 28, a graduate of Carmarthen School of Art who still lives in the town, chose to respond to the Jamaica map partly because of familial links with the island.

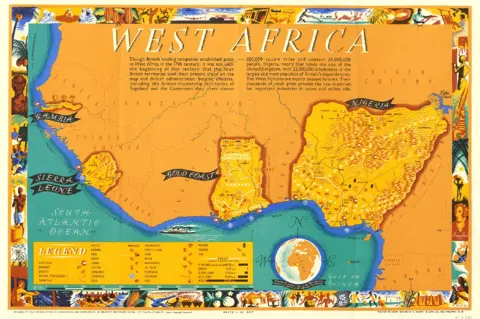

Her work and that of Mfikela Jean Samuel, who used a British Army map of west Africa from the 1940s for his inspiration, is being shown in the Wales to the World exhibition at the Riverside Gallery in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, until February.

Jasmine spent her early years living in Maidenhead, Berkshire, and moved to rural Ceredigion as a teenager when a visit to her father in Pont-rhyd-y-groes near Aberystwyth turned into a permanent move.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe said: "I just stayed because I loved Wales. It was only meant to be for a couple of weeks but I ended up loving it and never looking back really.

"It's a little village which is just off the [river] Ystwyth. It's really beautiful up there, completely in the sticks.

"It was very interesting going from suburban English life to moving to Wales into complete rural living but I ended up growing to love it."

The countryside which surrounded her is celebrated in the two works produced so far for the project, with a third nearing completion.

Working on the project took her art in a different direction to usual.

"I'd rarely do commission pieces which involve more historical things, so it was completely out of my comfort zone, but that's one of the reasons why I wanted to do it," she said.

National Library of Wales

National Library of WalesAlongside her art, she works part-time as a diversity and inclusion officer for the National Library and the commission gave her the opportunity to put her day job into her work.

"I'm really interested in decolonisation… and having the opportunity to react to this was really important to me as an artist," she said.

Having visited Jamaica and the Caribbean as a younger child, the work also gave her the chance to explore that side of her identity.

"I always say I'm too British to be Caribbean, but I'm too Caribbean to be British," she explained.

"Having an opportunity to say, this is my heritage, but really and truly what my culture is and what I've been brought up around is Britishness and Welshness, and that aspect of being a person of colour."

Jasmine Violet

Jasmine VioletLooking at a colonial map of plantations in Jamaica made her ask herself what her experience of nature and agriculture was.

Her conclusion was "being in Wales, in the valleys, with my brothers, with my family and friends by choice" where she could appreciate "beauty and the nature, and the things we grew in the garden and going out into the woods".

"It wasn't something which was forced; it was part of my [and my brothers'] lived experience."

She decided to celebrate these stories and "just living".

"I think that's part of the decolonisation journey which isn't talked about enough, [which] is actually saying there is so much to be celebrated and there's so many gaps in history of diverse groups which are celebrations rather than trauma.

"There are some amazing things which have happened in the present and in the past which we should highlight.

"So that's why I went down the route of doing landscapes of myself and my brothers in Wales because it is saying this is now, there is no difference between myself and everyone else.

"We still go out to nature because we love Wales and that's something that should be celebrated."

In addition, she considered the contrast between the lives of the ordinary people in Jamaica now and tourists.

National Library of Wales

National Library of Wales Mfikela Jean Samuel

Mfikela Jean Samuel"Something I always remember is the difference between the areas which have the hotels and the all-inclusives and stuff like that, and the just country village living, and people living their lives.

"That's almost still a separation which is still on many of the Caribbean islands."

And she was also conscious of many of the grimmer aspects of history which the collection invariably reflects.

"I think it's great that we're given the opportunity to show this and say this is some of the things which are negative, and to show a darker side of history.

"[To say these] are the people it affected and how they felt."

Simon Evans

Simon EvansEllie King, assistant map curator at the library who organised the Wales and the World exhibition, says it is important to remember that maps are not neutral documents but reflect the people who create them and "can mislead us".

"They can guide you to think of things in a certain way by what they show and they don't show," she said. "I'm really interested in that because... maps have a kind of veneer of scientific accuracy about them.

"You can have maps that are more or less geographically accurate. But the mapmaker is still deciding which things to show and which things not to show.

"A lot of the maps we have are military mapping so you get things that are of interest to armies and of interest to empire building, raw materials, resources, things like that."

The work produced by the artists surprised Ellie, given the sources' history.

Jasmine Violet

Jasmine Violet"They were both looking at maps with quite a difficult story behind them, especially Jasmine with the connections to the sugar plantations in Jamaica," she said.

"But both the artists created something kind of joyful and celebratory out of it.

"That's what we were hoping to get out of the project really, a perspective that we wouldn't necessarily have come up with ourselves and a new and unexpected way of looking at this material.

"So it's been fantastic from our point of view."

- BLACK MUSIC WALES: The artists who pioneered black music in Wales

- WALES' HOME OF THE YEAR: Which home will be crowned the winner?