Concorde: The Welshmen who got supersonic jets airborne

Evening Standard

Evening StandardConcorde is often heralded as a success of Anglo-French co-operation.

Yet what is frequently forgotten is the role two Welshmen played in making it a reality.

Sir Morien Morgan from Bridgend, "Father of Concorde", was the chief engineer of the project, whilst Brian Trubshaw of Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, was the first British pilot to fly the supersonic jet.

Between them they would go on to form the foundation of a true icon.

With commercial flights beginning 46 years ago this month, Concorde represented the pinnacle of both luxury and technology from 1976 to 2003.

For the small matter of £8,500 a ticket, its 120 pampered passengers were treated to champagne and caviar in plush leather seats designed by Terence Conran.

Not that they had all that long to take in the splendour, as flying at Mach 2, (1,347mph), trans-Atlantic crossing times between Britain and France and New York City were virtually slashed in half, to just over three hours.

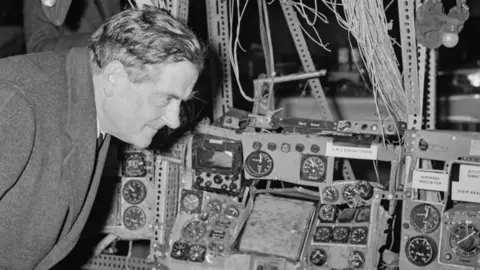

Morien Morgan was born in Caroline Street, Bridgend, on 20 December 1912, the son of a draper, who went to grammar school in Cardiff.

After studying at both Oxford and Cambridge universities, the precocious aeronautics engineer served a brief apprenticeship with Vickers, before joining the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in Farnborough, Hampshire, from 1935 where he specialised in aircraft control and stability.

On the centenary of his birth in 2012 when a blue plaque was unveiled at his childhood home, his daughter Prof Deryn Watson told BBC Wales: "There was no side to dad, he got on with everyone and told it like it was; that's probably how he was able to bring everyone together in the Concorde project in the way he did.

"A Welshman to the core, he never lost his Welsh accent, played the piano, sang in choirs, smoked a pipe, and frequently had a twinkle of amusement in his eyes."

She described how working on the stability of the Spitfire inspired him to believe that supersonic flight could well be possible.

"He loved the Spitfire, and I think there was something about the elegance of the design and the advanced engineering which gave him faith that faster-than-sound travel could be possible in the right hands," she added.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn November 1956 he became chairman of the newly formed Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee, or STAC.

Britain and France soon realised that both lacked the funds and know-how to launch such an ambitious project on their own, so on 29 November 1962 they signed a bilateral treaty to pool their resources against the competing American and Russian bids from Boeing and Tupolev.

In February 1965 construction of two prototypes finally began, with Concorde 001 being built by Aerospatiale (formerly SUD Aviation) in Toulouse and Concorde 002 by the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) in Filton near Bristol.

Morien Morgan's contribution was vital in securing the plane's eventual swept back delta wing design, tailless fuselage and distinctive droop nose for greater visibility during take-off and landing.

Though possibly his greatest role in the collaboration came in bringing all the engineers, French and British, together in one vision.

Mike Bannister, British Airways Chief Concorde Pilot, said: "Morgan the Supersonic as he was known to us was a legend while I attended the Hamble College of Air Training between 1967 and 1969.

"For all his engineering brilliance, he was a master diplomat, bringing together Britain and France at a time when they weren't exactly getting on.

"At that stage it needed someone with drive and panache; quite aside from the obvious language difference, British planes were also using imperial measurements and the French ones using metric measurements, yet, they still joined up. There were all of those challenges, but Morien, through pure will of character, made them come together."

Incredibly, from the signing of the treaty to the first test-flights in early 1969, the Anglo-British alliance managed to get Concorde in the air in less than seven years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProjected sales of 300 planes across 12 airlines only ever materialised into 14 between British Airways and Air France, although Concorde's undisputed technical brilliance put it on the global map.

Concorde 001 first took off from Toulouse on 2nd March 1969, and a month later on 9 April Brian Trubshaw piloted 002 on a short but momentous 25 minute maiden flight from Filton to nearby Fairford Aerodrome.

At the time of the first test flight Mike Bannister was a trainee pilot, about to embark on his career with BOAC, the predecessor to British Airways.

"I watched Brian Trubshaw's first Concorde flight on a black-and-white telly and I knew straight away that's what I needed to do with my life.

"Concorde training was intense but so much fun. It was a dream to fly, but after six months of five days a week on a residential course, by the weekend all you wanted to do when you got home was go to sleep."

Though Mr Bannister said it was all worth it.

Getty Images

Getty Images"It's like no other plane. When you're at 60,000ft you can see the curvature of the earth, and ordinary planes below you look as though they're moving backwards."

He added: "On an evening flight you take off from Heathrow in the dark and see the sun rise in the west, as you're flying faster than the earth is rotating beneath you."

It was all thanks to Brian Trubshaw, who'd enjoyed a very different background to Morien Morgan.

In comparison to Morgan's grammar school upbringing, Trubshaw came from an aristocratic family and attended Winchester College.

Born in 1924, after leaving the RAF, in 1950 he joined the Royal Flight and piloted George VI and his family on tours all over the world.

Queen Elizabeth is said to have referred to him as "My Little Brian"

He then became a test pilot for BAC, initially in Malaysia, before joining the Concorde project at Filton.

An ebullient character, Mike Bannister remembers him as being a driving force behind the mission.

"All through our training he was our hero, I was lucky enough to have him in the cockpit when we flew on our 10th anniversary flight."

However in 2000 the supersonic project came to a juddering halt when an Air France Concorde crashed shortly after take-off from Paris Charles de Gaulle airport. .

The accident investigation discovered the cause to be a metal strip dropped on the runway by a Continental Airlines 747, which burst the Concorde's tyre, causing the flapping rubber to penetrate the under-wing fuel tank.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite being modified with Kevlar under-wing coating and going back into service in November 2001, in 2003 Air France took the decision to retire their fleet, forcing British Airways to follow suit.

Mr Bannister explained that the crash was just one factor in French thinking, with others including cost-cutting ahead of Air France's privatisation, a lack of investment in the French fleet's cabins, and another serious incident in 2003.

He laments: "Over Concorde's lifespan the BA cabins were updated and modernised three or four times and always remained at the cutting edge of luxury, whereas the French fleet only ever received one facelift and so by the end were starting to look a little bit tired.

"Consequently the French began to fall out of love with Concorde, while British public confidence remained strong right up to its withdrawal.

"British Airways at least were making a profit from it, and if Air France hadn't have pulled out of the deal - increasing the BA maintenance costs from £60m to £100m a year - it could and should have flown for another 10 or 12 years; it was only halfway through its expected lifespan."

- A SPECIAL SCHOOL: Behind the scenes at a school like no other

- ICONIC WELSH PEOPLE, PLACES AND THINGS: Kiri Pritchard-McLean unearths the best clips from the BBC Wales archive