Falklands War: Veteran describes firing first shots

A veteran who fired the "first shots" of the main conflict in the Falklands War has described his experiences.

"I think I'd fused the depth charges [explosives] in about 10 seconds. In terms of the main conflict, this was the opening shot," Chris Parry said.

Later they learnt that they had been the first helicopter to ever engage a submarine and the first to disable a submarine since World War Two.

The 1982 conflict lasted 10 weeks and killed more than 900 people.

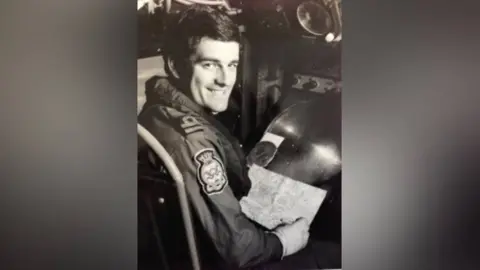

Mr Parry, from Hay on Wye, Powys, retired from the Royal Navy in 2007 as a rear admiral and operated on a Wessex 3 helicopter during the conflict in the Falkland Islands.

As a lieutenant in 1982, he was an observer on board, responsible for navigating, communications and weaponry.

The helicopter, named Humphrey, would become one of the most famous aircraft of the conflict. It now sits in the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton, Somerset.

During the opening days of the war in April 1982, his ship, HMS Antrim was getting indications of an Argentinian submarine nearby in the South Atlantic, close to the islands of South Georgia.

They convinced their captain to allow them to launch the helicopter and go in search of the submarine.

"We couldn't see a submarine or anything. And I suggested to my flight commander that we do one transmission on the radar," he said.

"So on the one sweep of the radar - which faded very quickly, I saw a small 'contact'. It was about six miles (9.6km) away, and so we closed in to have a look at it."

On finding the submarine they attacked immediately.

"We ran in, dropped the depth charges. One of them bounced off the casing [of the sub] the other one dropped alongside him and they both exploded and the whole back end of the submarine lifted out."

It was only on their return to the ship that they noticed the significance of the assault.

Chris Parry

Chris ParryIt was not Mr Parry's first involvement in the South Atlantic. His Wessex 3 anti-submarine helicopter had been involved in SAS landing attempts in South Georgia during the early days of the war.

One involved taking a team of soldiers up on to a glacier on the island, on a reconnaissance mission.

"It took us about eight attempts to get up on top of this glacier because of the conditions," he said.

A hurricane blew through from the Antarctic that night and the SAS team needed to be rescued.

He said: "It was quite difficult for us.

Chris Parry

Chris Parry"We, at one stage, lost rotor control and just spiralled down onto the glacier and luckily we regained it just before we hit the glacier. Another time we came out of a blizzard straight into a wall of mountain.

"At one stage we were flying along with a indicated airspeed of 100 and we just weren't going anywhere."

Eventually they were able to reach the SAS team. But two of the three helicopters involved in the rescue mission crashed.

He sent a radio message to the ship saying 'we've lost our two chicks [the helicopters]'.

"Helicopter control on the other end said 'you've lost what?' And I said 'we've lost our two chicks'.

"And it's just a stunned silence on the other end," said Mr Parry.

Fortunately, they were eventually able to rescue everyone involved.

"One guy said to me, he had never been so cold. In fact it was so cold, his teeth hurt even with his mouth shut."

Chris Parry

Chris ParryThe British landings on the Falklands started on the 21 May 1982, during which he navigated his team's Wessex 3 when they flew a group of Special Boat Service men on to the Falkland Islands, the first unit ashore of the main forces.

His ship, HMS Antrim went on to play a leading part in the assault on San Carlos, during which 49 British personnel were killed.

While on deck, he fashioned a gun position to "take pot-shots" at "anything that went by".

"What I thought I'd do is get a general purpose machine gun and use it while I was sitting on deck," he said.

"The only problem is that they're quite heavy and I had to improvise a swivel and what I got was one of the office chairs and I sort of strapped the [machine gun] to that."

Chris Parry

Chris ParryAfter the Argentinian jets left, the crew noticed "a bump in the flight deck underneath".

They found that an unexploded Argentinian bomb was "fizzing away" on the ship.

"We had to sort of sandwich it with mattresses and all sorts of other things to stop it rolling around," recalls Chris.

"We pulled the bomb out through two decks and very quietly put it over the side. And 15 minutes later we got a message from commander in chief fleet saying, 'on no account move the bomb'.

"But we did and we got rid of it."

Chris Parry

Chris ParryAlthough weaponry and fighting methods have developed over the years, looking back now as a professional strategic advisor, Mr Parry can see parallels with the ongoing war in Ukraine.

As a Spanish speaker, he interacted with Argentinian prisoners of war during and at the end of the conflict.

"Many of the conscripts thought or had been told that they were actually on the mainland of Argentina. Others were terrified of their officers."

While transporting two Argentinian soldiers, he said they feared being thrown from the helicopter.

"Because that had been what the regime in Argentina had been doing to its political prisoners.

"It was all I could do in Spanish to say to them, 'we're not gonna do anything, don't worry, it's fine'."

Despite the challenges they faced, he feels proud about actions of the British military in the Falklands.

"It was 8,000 miles away from home. And I don't think people realise quite how far that is. Everything that we fought with, we took with us.

"Did we go into the Falklands conflict with all the equipment we needed that we needed? No we didn't," he added.

"You have to accept that. You have to adapt, you have to improvise.

"Given all the challenges, I think the war was prosecuted the best way it could be to tell the truth.

"It was a great achievement by everybody.

"But I always think when I'm in Wales and I see commemorations of either the Falklands or in indeed of our deeper fighting tradition, I'm glad to be part of the Welsh race, and also that tradition."