Aberfan: Permanent home sought for disaster artefacts

Mike Flynn

Mike FlynnThe clock is stopped at 09:13.

More than half a century has passed since this once unremarkable timepiece came to awful prominence, as time stood still for a generation of children lost to the Aberfan disaster of 1966.

In the small Welsh mining village, 116 children and 28 adults died on 21 October when an unstable coal tip perched high above a south Wales valley slid down the mountain, engulfing Pantglas Junior School and nearby houses and burying the clock along with the victims.

The future of the clock and other items linked to the tragedy is now under discussion by their keepers, who worry what will happen when they are no longer here to look after them.

As news of the disaster spread that day, volunteers raced to help the rescue effort in a desperate battle against time to try to save those buried beneath the black waste.

PA

PAOne of those was Mike Flynn, who came with a paramedic group he had originally set up to assist the Territorial Army (TA) in Cardiff, 20 miles (32km) away, where he lived.

Amid the trauma of the day, the father-of-three unearthed the clock, which was to prove one of the enduring images of the tragedy.

The clock had stopped as the tonnes of debris struck the village. In the inquiry that followed, it was used to help pinpoint the precise time disaster struck.

The clock stayed in Mr Flynn's possession and in the course of time was passed on to his son, also called Mike.

Now 61, the younger Mike is starting to think of the clock's legacy and what will happen to it in the future

He recalls his father being away for the best part of a week helping in the aftermath of the disaster.

"When Aberfan happened, my father went across to the TA centre straight away and a group of them that were paramedics drove up in a van," he said.

"We saw literally when we got in the house from school, it was all that was on the black and white TV. It was just constant.

"Then I can remember seeing things about the Queen going up there and things like that.

"I can remember quite vividly afterwards because the impact on my dad was significant.

"He was on sleeping tablets for three years and, as a result of Aberfan, my father set up the local St John Ambulance division to do something with children."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMike spoke of a "ripple effect" that affected communities beyond the immediately bereaved people of Aberfan.

"There were so many miners that went in from other valleys, other pits," he said.

"There were people like my dad that were travelling up from other areas and I think that the impact that it had on my father... it lived with him."

It is why Mike feels strongly that items like the clock, which are part of the physical remembrance of Aberfan, need to be preserved.

He took the clock to Aberfan as part of the 50th anniversary commemorations in 2016, but for the rest of the time it remains tucked carefully away in his home.

Mike Flynn

Mike Flynn"The actual clock hasn't been photographed or out of its box for at least 10 years, apart from when I took it up to Aberfan," he said.

"That was the first time it had been there for 50 years since the accident, and literally the last time it ticked, all those children and adults were alive. It was quite a moving experience."

Mike would like to see the clock and similar items go on permanent display in a location like the St Fagans National Museum of History, on the outskirts of Cardiff, which documents Welsh life through the ages.

"I think it should be somewhere where there's a bit of a tribute," he said.

"I always felt that the [St Fagans] folk museum, because it is a museum of Welsh history, would be the most appropriate.

"In some respects you don't want something in the local community that would keep triggering negative memories because people need to move on, but on the flip side people should have a mechanism whereby they pay their respects if they feel there's a need.

"It is a fine balance to be struck."

'It's part of our history'

Gareth Jones is also conscious of the passing of time.

Aged six, he was one of the first children to be rescued from Pantglas Junior School after the coal waste hit.

He remembers the five-minute walk to school on a perfectly ordinary day, possibly with a bit more excitement because it was the last day of term, with a week's holiday to look forward to.

He said: "The big bell went, in we go into our classroom, sit down. It was an old school; the windows were above my head so I couldn't see out of them.

"Next thing there was this loud noise - we thought it was a jumbo jet. It was getting louder and louder and louder. [Then] the windows started coming in."

The class teacher got on top of a desk, smashed a window and helped get the children out to safety through it, Gareth recalled.

"I remember coming out of the window and looking to my left and thinking, 'that mountain wasn't there when we came in'," said Gareth.

"I went down to my mother's. In those days the front doors were always left open. It was a dark, miserable, wild day. It had been like that - raining and raining - for weeks."

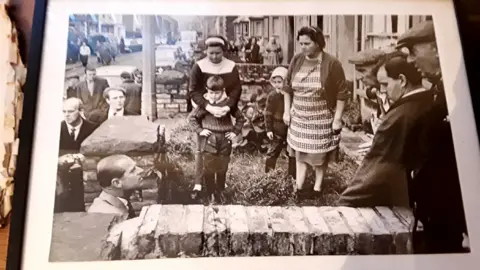

Gareth Jones

Gareth JonesHe called to his mother and said: "The mountain has come down on the school.

"She couldn't understand. She couldn't make head nor tail and I couldn't make head nor tail of what was going on."

Miraculously, both Gareth's older brother and sister escaped from the disaster and all three "huddled together on the stairs" once they all returned home, as water and slurry started soaking through their house, situated as it was at the bottom part of the valley.

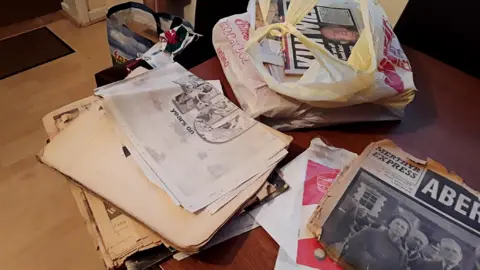

Gareth's parents, and later Gareth himself, amassed a collection of items and documents relating to the disaster, but many of them lay unseen for years.

Much of the memorabilia, in the form of newspaper reports and items like football programmes from charity matches played to raise funds for Aberfan families, was nearly lost when Gareth's father died and his mother moved to a smaller house.

"We had to chuck a lot of stuff out quite quickly. Underneath the stairs, where everybody kept everything, the last thing of all was all these plastic bags," he explained.

"I threw them out and one of the bags burst open. On the front of this newspaper was my mother, my brother and myself. I told my son not to get rid of them but to take them to my house. I'm so glad I didn't chuck them out.

"When we first opened them they were like new newspapers. They've yellowed now and got a bit brittle because I'm showing them to everybody.

"There was a picture on the wall of the Duke of Edinburgh when he came to Aberfan and I met him.

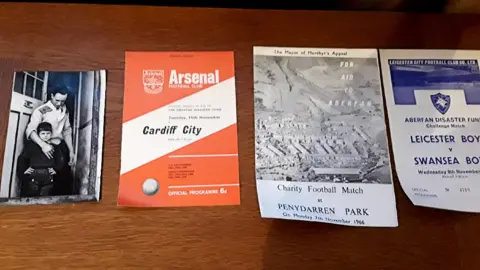

"There's loads of newspaper stuff that I've kept myself. Clips from interviews over the years. There's football programmes, charity matches, Cardiff City v Arsenal (played in November 1966 for the Aberfan Disaster Fund), Manchester United, Leicester."

Gareth Jones

Gareth JonesOther items stem from the period immediately after the disaster.

"We had toys given to us by Princess Margaret's own charity. In the old miners' hall, people were donating toys and clothing. All the boys in Aberfan had duffle coats and we all looked the same. We were like Stepford Wives," he joked.

"[From] Princess Margaret there was a big Scalextric set. Me and my brother had that. I've still got it today in the attic. I'd never chuck it away.

"To everybody else it's a lot of tat, but to me it's priceless."

He has spoken of the disaster to his three sons and given talks to local schoolchildren.

Gareth Jones

Gareth JonesBut he knows if the memorabilia he has amassed remains in his home, it will eventually be lost when he is no longer here.

"My children won't want it. They'll chuck it in the bin," he conceded.

"But to me it's part of our history. It was and still is a big part of my life. I'll never have closure on it because the only closure I'd ever have with it is somebody going to jail for it. We'll never get to see that.

"I'd like them to go somewhere where they'd be appreciated. Somewhere where other people can go and look at them. I don't want to do it straight away but when the time is ready I'd give them away."

Like Mike Flynn, Gareth thinks the National Museum of History would be a good home for an Aberfan exhibit, adding, "In St Fagans, it's Welsh history."

The museum told BBC Wales: "We already have items in Wales' national collections relating to Aberfan and are looking to collect more. Our curatorial staff are in touch with the owners of these iconic objects to discuss how we'd care for them and display them.

"Whilst collecting, we need to carefully consider the personal story of each object and what they mean to the community of Aberfan."

National Museum Wales

National Museum WalesDr Sarah May, senior lecturer in public history and heritage at Swansea University, said the Aberfan disaster was remarkably important in historical terms, not just to the people of the town but across south Wales and the wider country.

"It had repercussions in terms of understanding the responsibility of organisations that go much beyond the loss that people experienced that day," she said, adding the involvement of children in a mining disaster had prompted a different kind of response.

She is interested in the way people maintain memories through material culture - the physical things they have personally kept - as distinct from those held in museums.

Dr May explained: "There's this way in which people hold on to things for themselves to hold a memory. It can actually be therapeutic, and it can be something that is about respect and honour, a lot of different kinds of emotions, in holding onto an object.

"It also relates to this idea of an heirloom, that we hold onto things that hold respect for a previous generation."

However this can change over time as "the sense that an individual should hold something becomes less possible".

"So people come to museums and ask them to take that role," she said.

"The problem is that museums looking after things is a lot more expensive than anybody else looking after it."

Does Dr May think somewhere like the National Museum of History is an appropriate setting for a permanent exhibition?

She said: "It's clear that the community in Aberfan has been quite careful about how memorialisation works and it's clear that they have wanted to be able to hold their own space, and not let it be overwhelmed by everyone else's projections of what it might or might not have meant to them.

"I think it's appropriate that [any memorialisation] should be led by the community. It is they who experienced the loss.

"The idea of having memorials and a place to think about the disaster outside the village is also really helpful."

- SURVIVING HELMAND: Inspirational stories from those deeply affected by the conflict in Afghanistan

- TIP NUMBER 7: The families of Aberfan fight for justice