Great Strike trail marks 120 years since quarry dispute

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA historical trail is being unveiled to mark 120 years since one of Britain's longest industrial disputes divided a Welsh town.

The Great Penrhyn Strike started on 22 November, 1900, and lasted three years.

Now, a new self-guided "Slate and Strikes" tour using coded HistoryPoints markers retells the story in Gwynedd.

It uncovered tales of quarry spies, a battle between owners and unions, and bitter recriminations still felt today.

"It changed the town of Bethesda forever and contributed to the decline of the slate trade, with serious consequences for north Wales," said historian Dr Hazel Pierce, who advised the project.

Roaming across the quarry town, 19 points are marked with plaques, each bearing a QR code which can be scanned by a mobile phone.

It links to online information and stories about the location, and how it fits into the often turbulent history of the Great Strike.

HistoryPoints

HistoryPointsIt starts at the quarry itself, which still produces slate, but nothing on the scale of the early 20th Century.

At the time of the strike, Penrhyn Quarry was considered to be the largest slate quarry in the world, employing 2,800 men and swelling the population of Bethesda.

It turned from a rural village at the head of the Ogwen Valley in Snowdonia to a bustling town of 8,000 people.

It drew visitors from across the country to marvel at the massive quarry and its rock workings, including Queen Victoria.

But its owner had little time for the quarrymen, and even less for their unions.

George Sholto Gordon Douglas-Pennant -Lord Penrhyn - earned £133,000 from his quarry in 1899 - the equivalent of about £13.5m today.

But according to Dr Pierce, Lord Penrhyn held a deep-seated grudge against his workers after losing his seat in Parliament to the Liberals in 1880.

Lord Penrhyn declared Caernarfonshire the "lying county" and there "is no trust any longer to be in the word of a Welshman in this county".

The owner asked manager Emelius Alexander Young to turn paid informant and spy on his quarry workers, with men sent undercover to union meetings, reporting back to their lord and masters.

Determined to break the influence of the North Wales Quarrymen's Union, he abolished the "bargen" system of working at his quarry, where the men would negotiate the rate they were paid depending on the quality of the rock they had to work.

When the strike came, it split the community and families - those who worked and those who refused.

One plaque marks the home of Elizabeth Williams, brought before the courts for demonstrating in support of the men.

The prosecutor made it clear she was appearing to "serve as an example".

"The women of Bethesda are worse than the men," the court was told.

Dr Pierce said: "The women of Bethesda were important players in the strike, prominent in all the demonstrations and meetings, because many men had been forced to find work elsewhere.

"These were tough women, used to hardship and no mere bystanders in this."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor some, the actions of the owners strayed into territory of spiteful behaviour.

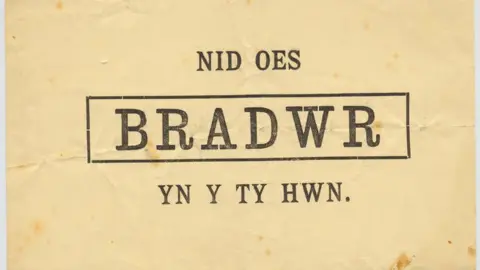

The tour takes visitors to the home of one tenant evicted by Lord Penrhyn for displaying the infamous Welsh notice: "Nid Oes Bradwr Yn Y Ty Hwn" - There is No Traitor In This House.

Lord Penrhyn's estate manager took over the cottage as his weekend retreat, boasting it was "one of the most delightful spots" he had ever seen.

In those three years, the town of Bethesda witnessed outbreaks of violence, with a revolver fired outside one strike-breaker's home, and pub windows smashed for serving those who went back through Penrhyn's gates.

People's Collection

People's CollectionArmed members of the military and large numbers of police were posted to the town, while the events were reported in national newspapers and discussed in the Houses of Parliament.

On 14 November, 1903, it all came to an end. The union had exhausted its funds, and the strikers and families were starving to death.

As they trickled back to work, William Hugh Williams, the financial secretary of the North Wales Quarrymen's Union remarked: "There was not enough wealth in the whole quarry to repay to them that which they had lost, for they had sold their own selves."

Just outside Bangor stands the magnificent National Trust property that was home to the Pennant family.

Even today, some residents of Bethesda and its communities - descendants of those strikers - still refuse to step inside Penrhyn Castle.