Face blindness: 'I can't recognise my loved-ones'

A stranger once waved at Boo James on a bus. She did not think any more of it - until it later emerged it was her mother.

She has a relatively rare condition called face blindness, which means she cannot recognise the faces of her family, friends, or even herself.

Scientists have now launched a study they hope could help train people like Boo to recognise people better.

Boo said for many years she thought she was "from another planet".

"It is immensely stressful and very emotionally upsetting to sit and dwell upon so I try not to do that," she said.

"It's very hard work. It can be physically and emotionally exhausting to spend a day out in public constantly wondering whether you should have spoken to someone."

For most of her life, she didn't know she had the condition - also known as prosopagnosia - and blamed herself for the "social awkwardness" caused when she failed to recognise people.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I had to try and find a way to explain that. I really couldn't very well, except to think that I was just the one to blame for not being bothered to remember who people were.

"[Like it was] some sort of laziness: I didn't want to know them, obviously I wasn't interested enough to remember them, so that was some kind of deficiency, perhaps, in me."

But the penny dropped in her early 40s when she saw a news item about the condition on television.

"I then knew that the only reason I wasn't recognising that person was because my brain physically wasn't able to do it," she said.

"I could immediately engage more self-understanding and forgive myself and try to approach things from a different angle."

She said her childhood was punctuated by "traumatic experiences" with fellow children, childminders and teachers she could not recognise.

And even now, the 51-year-old, of Loughor, Swansea, said she struggles to recognise her family and long-term friends, including failing to recognise her father while meeting him during a holiday.

But she also finds it very difficult to recognise someone even more fundamental.

"Recently, my mother said she'd found some old photos on her computer, so we were looking at them on screen," she said.

"She was talking about one person in a picture and I said 'OK, but who on earth is that other person?' She said, 'well, that's you!'"

Boo describes her partner, Dewi, as her "seeing dog for the face blind" because he will try to discreetly tell her if someone they're talking to is someone she knows.

He is also on hand to explain the plot and identify characters in films, which would be otherwise "impossible " for her to follow.

"He's very kind and very patient and he perseveres. Just occasionally we switch a film off because it just gets too complicated," she said.

But how do people with prosopagnosia perceive faces? Those with the condition say it can be difficult to describe.

"I can see component parts of a face," Boo said. "I can see there's a nose, I can see there are eyes and a mouth and ears.

"But it's very difficult for my brain to hold them all together as the image of a face."

She now works from home as a writer and says the condition has impacted on her career, making her time in retail and as a receptionist "very awkward".

"People come in and see you regularly, and they know you but you're looking at them and you're not sure about your history with these people," she said.

However, despite the limitations, Boo believes she has developed tactics and techniques which allow her to often figure out who's who.

"I do have a whole other palette I can use: hairstyles; a piece of jewellery someone might wear regularly; the way that someone dresses; people's voices, once they start talking; even the silhouette of someone, their body shape, the way that people talk.

"I'd like to think I'm better at recognising people from behind than your average person," she explained.

It is believed up to one in 50 people have some form of developmental face blindness, although not as all profoundly as Boo.

Richard Warr, from Cardiff, a marketing lecturer at the University of Gloucestershire, has prosopagnosia to a much less severe degree.

He said: "It's mainly with people that I don't know that well, so people I have maybe met very briefly or for people I've only know for a few days or a few weeks."

He added: "Overall, it's not something that majorly impacts on my life, but it's something that's there and I do need to deal with quite often.

"Especially with new students coming in or meeting new people."

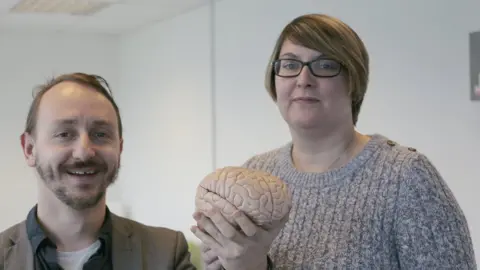

Academics carrying out the new research at Swansea University want people to come forward who may have experienced difficulty in recognising faces, as many have no idea they have prosopagnosia.

"This is the kind of person who maybe finds films a little bit difficult to follow," said Swansea University psychologist, Dr John Towler.

"Maybe they were watching Game of Thrones and everyone's got long hair and beards and they've got no idea what's going on.

"It's only through raising awareness for prosopagnosia that people are starting to realise 'maybe that's me'."

There are two kinds of prosopagnosia.

Acquired prosopagnosia is a result of brain damage from injury to parts of the brain that control facial recognition, while developmental prosopagnosia, which affects those with face blindness from birth, arises from a breakdown in communication between different parts of the brain.

Dr Jodie Davies-Thompson, who is also part of the research team, said: "If we can really work out exactly which part of the brain is going wrong, then we can start to look at remediation of this problem.

"We're working here at Swansea at developing a rehabilitation programme for people with prosopagnosia.

"We're hoping that will increase the connections between the areas and therefore increase their ability to recognise faces."

Support group, Face Blind UK, said the experiences of people like Boo and Richard were not uncommon and greater awareness really helped.

"If other people are aware of the difficulties then they can begin to understand, and even offer help," spokeswoman, Hazel Plastow, said.